Later, before he was sent to Spandau to serve this sentence, Speer was called, as a witness for the defence, to testify in the trial of Field Marshal Milch of the Luftwaffe (this was one of the first trials under the Subsequent Proceedings). I had once again gone into the English booth to interpret his testimony. When the mid-day recess was called, Speer asked permission to remain in the courtroom and expressed the hope that he would be allowed to talk to me if I were willing. Naturally, I was.

We sat down in a corner of the courtroom – much to the annoyance of the guards who had to go on hovering instead of playing cards somewhere – and Speer explained his somewhat unusual request for our cosy chat.

He had deduced from my strong tan that I was a skier. He was a keen skier himself, he said, and a mountaineer, and he had this need to talk to somebody about this hobby. It turned out that his forte was cross-country skiing in the mountains and he knew of many mountain huts in the Alps; we did, in fact, make some sort of an appointment to meet in such a refuge after his release, twenty years hence, during the first week of the following February. (As it turned out when he was freed from Spandau his eyesight had deteriorated so badly that he could not have kept our date).

We talked a lot about architecture, sports, travel, the theatre and many other subjects of that kind but not a word was said about the trial, his sentence, or that part of his life that had led to his imprisonment.

Albert Speer was the only one of all the guilty men I met before and during Nuremberg for whom I developed a liking; because here was an outstandingly intelligent man who conveyed, throughout our conversation, a very clear sense of guilt that he would carry with him for the rest of his life. There was none of the maudlin self-incrimination I had heard from the other Nazis – high ranking and low ranking – nor was an accusing finger pointed at the Fuehrer, or polemics put forward against the trial and the right of the victor to try the vanquished. It was clear that Speer had come to terms with the past, the present and the future – and himself.

‘Can twenty years imprisonment be termed future?’ I asked him.

‘The twenty years will pass,’ he replied wistfully, ‘survival is so much a question of one’s inner attitude, of willpower. Yes, I will survive that sentence, I am sure. I will write, and I will paint – I haven’t had time to paint. Now I will – landscapes. It will serve a double purpose. I will be occupied, and I will train my imagination to visualise the things I won’t be able to see – mountains, trees, the countryside, colours. Physically, I will be in a cell, but my mind won’t be.’

I nodded, without comment. ‘See you up there in that hut, in twenty years,’ I said as I was leaving. But the story ends here; neither of us could keep the appointment.

Soon after my return to Nuremberg I wore another of the new suits on an illicit outing run by the US Army in Feldafing. I decided to go not as an ex-British officer but as a heavily disguised, strongly accented civilian of un-definable origin. I spent hours at a theatrical hairdresser’s shop in Munich having a false beard constructed whisker by whisker and with added dark sunglasses I looked exactly like the Dr Morrison I professed to be.

I hadn’t been at the party long when a slightly drunk lieutenant got hold of me and said. ‘Some friends want to see you in the library – now!’

Three officers were waiting for me one of whom, a captain, was waving a service revolver in my face. He shoved me in a chair, rather brutally, and tore off my beard. These officers, so I was to discover, were attending the US Army Intelligence School. They were too sharp for words, had seen there was something sinister and were determined to unmask me. I was manhandled, and my credentials were declared to be forgeries. Fortunately, the colonel, who lived on the premises, knew me and came to my rescue. However, I was kicked out and told never to return by one Lieutenant Benny Schaefer, or Scheffer.

On my way back to Nuremberg I got my dander up. Yes, I had been out of line with my false beard and brand new suit, but the Americans involved were far more out of line: US officers on active duty fraternising with German girls; supporting a German ménage with US Army rations; providing US Army liquor for a German party; hobnobbing happily with a bunch of ex-Nazis I had seen in attendance; using threatening behaviour towards an only slightly disguised high ranking British civilian who was carrying proper identification. No, I will not stand for this, I thought.

The following morning, I attacked. I went to see Sir David Maxwell Fyfe, head of the British contingent, whom I knew well, and I told him all. He listened to me and managed a frown. I had, he said, been foolish and indiscreet.

‘Be that as it may,’ I said, ‘however, the Americans had been guilty of appalling behaviour towards an Englishman. Towards, in fact, the British delegation at the trial.’

Sir David saw my point and said he would take it up with General Leroy Watson the US CO at Nuremberg. He too saw things our way and went straight into action by calling the CO at the Intelligence School and suggesting Benny Schaefer should be sent home forthwith. A couple of days later I was called in to Sir David’s office. The small group assembled there included, in rank order: General Watson, a major, Lieutenant Benny boy, and an agitated US Congressman, whose eyes were red-rimmed from lack of sleep. He, it turned out, was Benny’s dad and he had rushed across the Atlantic, at US taxpayers’ expense, to get his offspring off the hook.

Apologies were delivered. Benny was allowed to stay in Europe and I got much more fun out of it than I had anticipated.

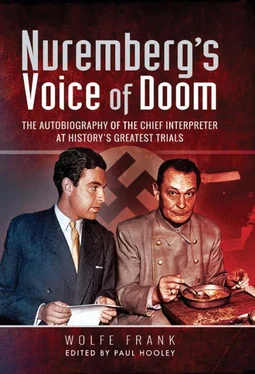

33. TRANSLATING FOR GOERING

BACK AT THE TRIBUNAL I gave a marathon performance in the English booth when Goering took the stand. The BBC had wanted me to interpret as much of his testimony as I could manage since they preferred my voice and delivery to that of my colleagues.

My interpretation would be going out over every English-speaking network around the world – Great Britain, the USA, Canada, Australia, South Africa and the rest – amounting to several hundred million listeners. Dostert had given his blessing and the other two German-English interpreters had no objections.

I stayed on microphone for the whole of the first morning of Goering’s direct examination by his counsel, Dr Stahmer, a total of three hours, worked for the first half of the afternoon and then continued on the following morning. In total I did nearly nine of the thirteen hours of Goering’s testimony.

His performance was fascinating, indeed. The contents have been so thoroughly analysed, commented upon and criticised that I need not add to them here. However, the account, given to me by one of Dr Stahmer’s colleagues, of how Goering set the scene, might be of interest.

It seems that the little lawyer from Hamburg was in a state of panic because twenty-four hours before Goering was to take the stand he had not yet consulted his counsel regarding the details of his testimony. Then, at the last moment, he sent for Stahmer. Cutting short any of the doctor’s queries or suggestions, the former Reichsmarschall dictated several hundred questions, and ordered his despairing legal adviser to ask those questions, in that order, once he, Goering, had taken the stand. No ifs, no buts – this is an order. Stahmer tried in vain to discover the story line which would link them but time was too short and the subject too vast.

Читать дальше