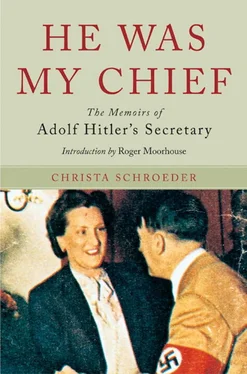

Christa Schroeder - He Was My Chief - The Memoirs of Adolf Hitler's Secretary

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Christa Schroeder - He Was My Chief - The Memoirs of Adolf Hitler's Secretary» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Город: Barnsley, Год выпуска: 2012, ISBN: 2012, Издательство: Frontline Books, Жанр: История, Биографии и Мемуары, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:He Was My Chief: The Memoirs of Adolf Hitler's Secretary

- Автор:

- Издательство:Frontline Books

- Жанр:

- Год:2012

- Город:Barnsley

- ISBN:978-1-7830-3064-4

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

He Was My Chief: The Memoirs of Adolf Hitler's Secretary: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «He Was My Chief: The Memoirs of Adolf Hitler's Secretary»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

He Was My Chief: The Memoirs of Adolf Hitler's Secretary — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «He Was My Chief: The Memoirs of Adolf Hitler's Secretary», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Lacking regulated duties or a service schedule she formed part of Hitler’s most intimate circle which served him as a kind of substitute family. Depending on his mood when the evening ‘tea hour’ began, he would deliver to his captive audience his endless monologues into the early hours. Christa Schroeder summarized her unhappy existence:

15 years of service, three of them with the Supreme SA leadership (OSAF) and its Economics Department, in between a couple of weeks break with the Reich Leadership of the Hitler Youth, and twelve years in the personal adjutant of the Führer and Reich Chancellor; these were for me 15 years cloistered away from a normal, everyday, civilized existence. A life behind defences and guarded barbed wire fences, especially during the war years in the various FHQs.

On 30 August 1941 she wrote to her friend Johanna Nusser from FHQ Wolfsschanze, Rastenburg in East Prussia:

Here in the compound we come up eternally against sentries, eternally have to show our identity papers, which makes one feel trapped. I believe that after this campaign I should make the effort to make contacts with life-affirming people beyond our circle, for otherwise I shall become withdrawn and lose contact with real life. Some time ago this sense of being hemmed in, this being shut away from the rest of the world, became etched in my consciousness. Walking inside the fence, passing sentry after sentry, I realized that it is really always the same whether we are in Berlin, on the Berg [10] From 1936 Hitler’s house on the Obersalzberg was given the name ‘Berghof’. Hitler’s Staff and the inner circle always referred to it as ‘the Berg’. On 2.2.1942 at FHQ Wolfsschanze, Hitler stated that the Berghof was also ‘Gralsburg’ (The Grail Fortress). Heinrich Heim: Adolf Hitler, Monologe im FHQ , 1941–1944.

or travelling: always the same old circle of faces, always the same round. In that there lies a great danger and a powerful dilemma from which one longs to be free but then, once beyond it, one knows not where to begin because one has to concentrate so utterly and totally on this life, precisely because there is no possibility of a life beyond this circle.

After the war she concluded:

Belonging to Hitler’s intimate Staff, always treated as persona grata , all the instincts of struggle in one’s personality remained underdeveloped. And how they were needed in the situation at the war’s end, at the disintegration of the Third Reich and during my three-year internment in Allied camps and prisons. It was in such a condition, rather like an egg without a shell, that on the night of 20 April 1945 in company with my old colleague Johanna Wolf, Adolf Hitler took his leave of us and told me to get away from Berlin for a dark, uncertain future, of which I had no foreboding that the 15 years past and the three years of internment ahead would leave an indelible physical and psychic mark on me which I still have to this day. My past has demanded much of me, both now and when the past was still the present. It does so today to a much harsher degree!’

Anton Joachimsthaler Munich, June 1985Chapter 1

How I Became Hitler’s Secretary

AS A YOUNG GIRL I wanted to see Bavaria. I was told it was very different there from central Germany where I had grown up and spent all 22 years of my life. So, in the spring of 1930, I arrived in Munich and started to look for work. I had not studied the economic situation in Munich beforehand and I was therefore surprised to find how few job opportunities there were and that Munich had the worst national rates of pay. I turned down some work offers hoping to find something better, but soon things began to get difficult, for my few savings were quickly melting away. As I had resigned of my own accord from the Nagold attorney whom I had used as a springboard to Bavaria, I was unable to claim unemployment benefit.

When replying to an extremely tiny advertisement written in shorthand cipher in the Münchner Neuesten Nachrichten , I had no premonition that it was to open the doors to the greatest adventure, and determine the future course of my life, whose effects even today I am still unable to shake off. I was invited by an unknown organisation, the ‘Supreme SA leadership (OSAF)’ to present myself in the Schellingstrasse. In this almost unpopulated street with its few businesses the Reich leadership of the NSDAP, the Nazi Party, was located at No. 50 in the fourth floor of a building at the rear. In the past, the man who would later become Adolf Hitler’s official photographer, Heinrich Hoffmann, had made his scurrilous films in these rooms. The former photographic studio with its giant oblique window was now occupied by the Supreme SA-Führer, Franz Pfeffer von Salomon and his chief of staff, Dr Otto Wagener.

Later I learned that I had been the last of eighty-seven applicants to keep the appointment. That the choice fell on me, a person being neither a member of the NSDAP nor interested in politics nor aware of who Adolf Hitler might be, must have resulted purely from my being a twenty-two year old with proven shorthand-typing experience who could furnish good references. I also had a number of diplomas proving that I had often won first prize in stenographic competitions.

Below the roof at No. 50 was a very military-looking concern, an eternal coming and going by tall, slim men in whom one perceived the former officer. There were few Bavarians amongst them, in contrast to the majority of men on the lower floors where other service centres of the NSDAP were located. These were predominantly strong Bavarian types. The OSAF men appeared to be a military elite. I guessed right: most had been Baltic Freikorps fighters. [11] ‘Baltic fighters’ were members of the various German Freikorps who united with Baltic nationals in 1918–19 to resist the advance of the Red Army and secure the German eastern border. In the autumn of 1919, Germany had about 420,000 Freikorps men under arms. Many of these militants went later to the NSDAP.

The smartest and most elegant of them was the Supreme SA-Führer himself, retired Hauptmann Franz Pfeffer von Salomon. After the First World War he had been a Freikorps fighter in the Baltic region, in Lithuania, Upper Silesia and the Ruhr. In 1924 he was NSDAP Gauleiter (head of a provincial district) in Westphalia, and afterwards the Ruhr. His brother Fritz, who had lost a leg and was prematurely grey, functioned as his IIa (Chief of Personnel).

In 1926 Hitler had given Franz Pfeffer von Salomon the task of centralising the SA men of all NSDAP districts. Originally, every Gauleiter ‘had his own SA ’ and his own way of doing things. Many were ‘little Hitlers’, which certainly did not serve the interests of unity in the Movement. As Hitler took upon himself the decision in all matters of ‘degrees of usefulness’, he considered it opportune to suppress the Gauleiters by centralising the SA. This was a clever chess move, for he envisaged the SA as the sword by which he proposed to force through the political will of the Party. Since this struggle did not go his own way, Hitler delegated this unpleasant job to Hauptmann Salomon. This ‘keeping myself out of it’ was a crafty move to which Hitler often resorted later. The Gauleiters were incensed by the reduction in their power, went all out for Salomon and constantly reported their worst suspicions about him to Hitler. Hitler had of course expected this, which was the main reason for his having delegated the job, and no doubt he gave an inward smile of satisfaction at his own foresight.

In August 1930 Hitler was obliged to give in to the pressure of the trouble-makers and sacrificed Pfeffer von Salomon, something which to all appearances he regretted having to do, although he did not much like the man. After making it clear that Salomon had outlived his usefulness, the latter resigned in August 1930, and Hitler took the opportunity to appoint himself Supreme SA-Führer in his place. Franz Pfeffer von Salomon was a critical sort of man. I often had cause to confirm this. One day for example I saw a copy of the Party newspaper Völkischer Beobachter lying on his table. It showed a photograph of Hitler. Salomon had doodled Hitler’s filthy, unkempt uniform jacket into a slim, tailored shape. The debonair Salomon seemed to find Hitler’s figure and manner of dressing, as probably much else, apparently not to his taste.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «He Was My Chief: The Memoirs of Adolf Hitler's Secretary»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «He Was My Chief: The Memoirs of Adolf Hitler's Secretary» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «He Was My Chief: The Memoirs of Adolf Hitler's Secretary» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.