These were the facts, not that I heard them from my father. I read about them in old issues of Yank magazine and other Army publications that kept track of his unit, the 133rd Engineers Division. I always asked him if he’d killed the soldier whose German helmet, complete with swastika decal above the rain curl, he’d brought back from the war. His standard answer was “He saw me, I saw him, we both fainted, but I woke up first.” My mother, though, said Dad had killed the guy. “Shot him. Dead. The Nazi,” she said, which definitely provided me with bragging rights down at the park.

What was true I never knew, but my father didn’t care if we used the helmet for our war games. One day Dad saw me carrying my air rifle with the helmet on my head. “Oh, so today you’re the Nazi,” he said with a shrug, and went back to pruning his rosebushes.

Rabbi Adler’s act, however, got under my father’s skin. Later that night I heard him and my mother arguing about it. “He did that on purpose, ” my father said to my mother, who told him to keep his voice down. The incident was not mentioned again. It was near the end of the school year and Rabbi Adler did not return, replaced by other scary bearded men from nightmare worlds across the sea. But still, I think about why my seeing Adler’s number tattoo upset my parents so. What was he showing me, after all, but history, what had happened to people for no other reason than that they were Jewish—Jewish like me, regardless of what the rabbi thought?

I didn’t quite get it until many years later, after both my parents were dead. I went to a funeral for a great-aunt of mine, the sister of my father’s father, Harry. There were twelve of them to begin with, eight boys and four girls. Some I knew, some I had never met, like the celebrated Uncle Larry, the family gangster who once, as the story went, won a Mott Street Chinese restaurant playing craps in a downtown opium den. The fact that he lost the restaurant to another gambler a couple of weeks later mattered little. For decades after, when anyone in the family craved a bowl of yat gaw mein, we always went to “Uncle Larry’s,” out of loyalty.

My great-aunt was the last of them, well into her nineties when she died. I drove out to the cemetery for the funeral and there they were: all the headstones, one for each brother and sister, none on this earth for less than sixty years. Their parents had bought that one-way ticket to Ellis Island in the nick of time; they’d all gotten out, not one of them had ever been sent to a death camp or had their skin turned into a lampshade by Ilse Koch. It was something to feel good about: their bones planted in the dispassionate earth of Nassau County.

This, I decided, was the key to my father’s long-ago rage. It wasn’t as if our family was so smart. There were plenty of others way smarter than us and they had been caught and killed. You couldn’t just call us lucky, either. Dad would spend long afternoons playing blackjack in Atlantic City casinos when he was dying of kidney failure and wound up having a heart attack instead. He knew the limits of luck. The reason we had survived to thrive in this, our wondrous Queens Utopia, transcended luck or brains. You couldn’t call it a smattering of benevolence on harsh Yahweh’s part, either, because my father never believed in any of that. The way things worked out was beyond any accounting, not to be taken for granted but simply accepted. What had happened to Rabbi Adler and his people was their problem. We were Americans, citizens of the true promised land. Adler had “no business” trying to infect me, the blessed son, with their misfortune.

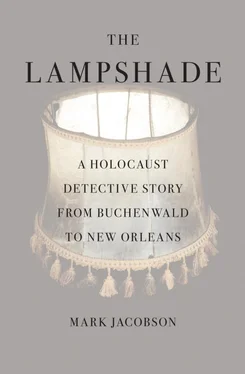

I appreciate my father for this sentiment, if indeed that was what he was thinking. No doubt he felt he was looking out for me. But as the sign on the Buchenwald gate says, Jedem Das Seine , you are who you are. And now that this stupid lampshade had arrived in my life, certain existential details could no longer be overlooked.

New York has gone through many changes since I ran free with my friends in as yet unsubdivided Queens. One thing remains the same, however. Even since Rudolph Giuliani supposedly cleaned up the town, there are still a lot of ways to wind up dead in the big city. Anyone who spends any time working at the Office of the Medical Examiner—what most people call “the morgue”—gets used to seeing all kinds of bodies. Shot bodies, stabbed bodies, poisoned bodies, strangled baby bodies, beaten-to-death bodies, to say nothing of so-called naturally diseased bodies and bodies whose vital parts are simply too far out of warranty to keep on ticking.

No morgue worker, however, had ever seen anything like September 11, 2001. From the first moments after the planes smashed into the Trade Center towers, the medical examiner’s office was on full alert, ready for the unprecedented carnage certain to follow. Early estimates said as many as ten thousand people could be dead.

“That was the eeriest thing,” says Shiya Ribowsky, who was Director of Special Projects at the ME’s office on 9/11, “standing around on Thirtieth Street at the office waiting for the bodies. Bodies that never came. That’s when we began to realize the scope of what had happened. We weren’t going to get any bodies. Not intact, anyhow. What was coming would be pieces of bodies, if that.” Over the next several months Shiya Ribowsky and his coworkers at the examiner’s office spent as many as sixteen hours a day attempting to sort the remains of the people killed at the World Trade Center, some of whom would take years to identify.

I got Shiya Ribowsky’s name from a former NYPD homicide detective who spent a long time working on missing persons cases. “Try this guy. I met him at the ME’s office,” the cop said, in his cop way, offering the name, the phone number, and nothing else.

Truth be told, I’d been dragging my feet on the lampshade. In fact, I’d done almost nothing about it in the four months since it had arrived from New Orleans other than to stick it in a closet. When Skip Henderson called, as he often did, to find out “What’s up with the lampshade?” I told him I was working my way up to it. After all, I was busy, a working man with things on my mind. Even if what Dave Dominici had said was true, a long shot at best, the thing had been lying around for more than sixty years. Another couple of months wouldn’t hurt. No need to rush into things.

Every so often, however, I’d take it out of the box, give it a onceover. On the surface, the thing didn’t look all that creepy. If you didn’t know —if the idea hadn’t been planted in your head—it would have been very easy to walk past the shade in some dusty secondhand store. Even if you did stop to pick it up and inspect the oxidized metal frame and the parchment panels, what would you see? Just a vaguely antiqueish table lampshade with some cheesy boudoir tassels in the shape of little bells hanging off the bottom.

Not knowing the story, a person might easily enough confront the lampshade armored with the rational. After all, if there was one thing everyone had heard about human skin lampshades, especially the human skin lampshades associated with the so-called Bitch of Buchenwald, it was that they were made of tattooed skin. That was the whole decorative scheme, so to speak. The lampshade that the heavily tattooed Skip Henderson bought from the equally heavily tattooed Dave Dominici had no such markings. It was tattoo free. Beyond that, the standard opinion among scholars (it is now possible to get a Ph.D. in “Holocaust studies”) had long been that Ilse Koch did not make “hundreds” of human skin lampshades as Emanuel Celler had contended. In fact, as with the equally celebrated case of the soap the Nazis supposedly made from “Jewish fat,” many historians now believed the lampshades, if they existed at all, were quite peripheral to the vast story of the Holocaust, that they were possibly even illusionary tchotchkes of terror, the product of Allied propaganda and the brutalized imagination of prisoners.

Читать дальше