Not surprisingly, then, positive psychology has become the trendiest subfield of the discipline. In the 1990s leading experts such as Martin Seligman, Ed Dinner and Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi argued that psychology should study not just mental illnesses, but also mental strengths. How come we have a remarkably detailed atlas of the sick mind, but have no scientific map of the prosperous mind? Over the last two decades, positive psychology has made important first steps in the study of super-normative mental states, but as of 2016, the super-normative zone is largely terra incognita to science.

Under such circumstances, we might rush forward without any map, and focus on upgrading those mental abilities that the current economic and political system needs, while neglecting and even downgrading other abilities. Of course, this is not a completely new phenomenon. For thousands of years the system has been shaping and reshaping our minds according to its needs. Sapiens originally evolved as members of small intimate communities, and their mental faculties were not adapted to living as cogs within a giant machine. However, with the rise of cities, kingdoms and empires, the system cultivated capacities required for large-scale cooperation, while disregarding other skills and talents.

For example, archaic humans probably made extensive use of their sense of smell. Hunter-gatherers are able to smell from a distance the difference between various animal species, various humans and even various emotions. Fear, for example, smells different to courage. When a man is afraid he secretes different chemicals compared to when he is full of courage. If you sat among an archaic band debating whether to start a war against a neighbouring band, you could literary smell public opinion.

As Sapiens organised themselves in larger groups, our nose lost its importance, because it is useful only when dealing with small numbers of individuals. You cannot, for example, smell the American fear of China. Consequently, human olfactory powers were neglected. Brain areas that tens of thousands of years ago probably dealt with odours were put to work on more urgent tasks such as reading, mathematics and abstract reasoning. The system prefers that our neurons solve differential equations rather than smell our neighbours. 5

The same thing happened to our other senses, and to the underlying ability to pay attention to our sensations. Ancient foragers were always sharp and attentive. Wandering in the forest in search of mushrooms, they sniffed the wind carefully and watched the ground intently. When they found a mushroom, they ate it with the utmost attention, aware of every little nuance of flavour, which could distinguish an edible mushroom from its poisonous cousin. Members of today’s affluent societies don’t need such keen awareness. We can go to the supermarket and buy any of a thousand different dishes, all supervised by the health authorities. But whatever we choose – Italian pizza or Thai noodles – we are likely to eat it in haste in front of the TV, hardly paying attention to the taste (which is why food producers are constantly inventing new exciting flavours, which might somehow pierce the curtain of indifference). Similarly, when going on holiday we can choose between thousands of amazing destinations. But wherever we go, we are likely to be playing with our smartphone instead of really seeing the place. We have more choice than ever before, but no matter what we choose, we have lost the ability to really pay attention to it. 6

In addition to smelling and paying attention, we have also been losing our ability to dream. Many cultures believed that what people see and do in their dreams is no less important than what they see and do while awake. Hence people actively developed their ability to dream, to remember dreams and even to control their actions in the dream world, which is known as ‘lucid dreaming’. Experts in lucid dreaming could move about the dream world at will, and claimed they could even travel to higher planes of existence or meet visitors from other worlds. The modern world, in contrast, dismisses dreams as subconscious messages at best, and mental garbage at worst. Consequently, dreams play a much smaller part in our lives, few people actively develop their dreaming skills, and many people claim that they don’t dream at all, or that they cannot remember any of their dreams. 7

Did the decline in our capacity to smell, to pay attention and to dream make our lives poorer and greyer? Maybe. But even if it did, for the economic and political system it was worth it. Mathematical skills are more important to the economy than smelling flowers or dreaming about fairies. For similar reasons, it is likely that future upgrades to the human mind will reflect political needs and market forces.

For example, the US army’s ‘attention helmet’ is meant to help people focus on well-defined tasks and speed up their decision-making process. It may, however, reduce their ability to show empathy and tolerate doubts and inner conflicts. Humanist psychologists have pointed out that people in distress often don’t want a quick fix – they want somebody to listen to them and sympathise with their fears and misgivings. Suppose you are having an ongoing crisis in your workplace, because your new boss doesn’t appreciate your views, and insists on doing everything her way. After one particularly unhappy day, you pick up the phone and call a friend. But the friend has little time and energy for you, so he cuts you short, and tries to solve your problem: ‘Okay. I get it. Well, you really have just two options here: either quit the job, or stay and do what the boss wants. And if I were you, I would quit.’ That would hardly help. A really good friend will have patience, and will not be quick to find a solution. He will listen to your distress, and will provide time and space for all your contradictory emotions and gnawing anxieties to surface.

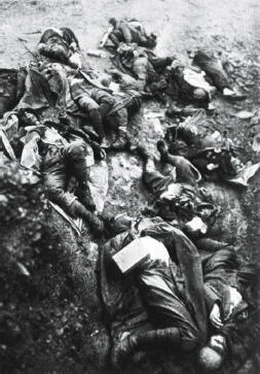

The attention helmet works a bit like the impatient friend. Of course sometimes – on the battlefield, for instance – people need to take firm decisions quickly. But there is more to life than that. If we start using the attention helmet in more and more situations, we may end up losing our ability to tolerate confusion, doubts and contradictions, just as we have lost our ability to smell, dream and pay attention. The system may push us in that direction, because it usually rewards us for the decisions we make rather than for our doubts. Yet a life of resolute decisions and quick fixes may be poorer and shallower than one of doubts and contradictions.

When you mix a practical ability to engineer minds with our ignorance of the mental spectrum and with the narrow interests of governments, armies and corporations, you get a recipe for trouble. We may successfully upgrade our bodies and our brains, while losing our minds in the process. Indeed, techno-humanism may end up downgrading humans. The system may prefer downgraded humans not because they would possess any superhuman knacks, but because they would lack some really disturbing human qualities that hamper the system and slow it down. As any farmer knows, it’s usually the brightest goat in the herd that stirs up the greatest trouble, which is why the Agricultural Revolution involved downgrading animal mental abilities. The second cognitive revolution dreamed up by techno-humanists might do the same to us.

The Nail on Which the Universe Hangs

Techno-humanism faces another dire threat. Like all humanist sects, techno-humanism too sanctifies the human will, seeing it as the nail on which the entire universe hangs. Techno-humanism expects our desires to choose which mental abilities to develop, and to thereby determine the shape of future minds. Yet what would happen once technological progress makes it possible to reshape and engineer our desires themselves?

Читать дальше

Конец ознакомительного отрывка

Купить книгу