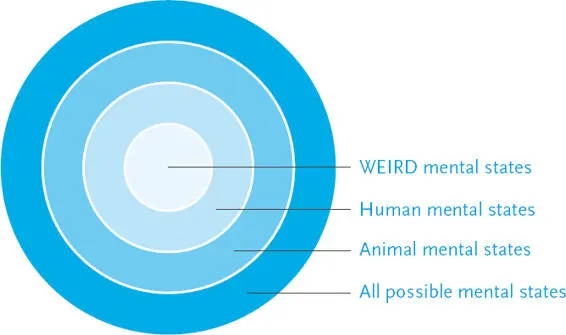

Before the emergence of the global village, the planet was a galaxy of isolated human cultures, which might have fostered mental states that are now extinct. Different socio-economic realities and daily routines nurtured different states of consciousness. Who could gauge the minds of Stone Age mammoth-hunters, Neolithic farmers or Kamakura samurais? Moreover, many pre-modern cultures believed in the existence of superior states of consciousness, which people might access using meditation, drugs or rituals. Shamans, monks and ascetics systematically explored the mysterious lands of mind, and came back laden with breathtaking stories. They told of unfamiliar states of supreme tranquillity, extreme sharpness and matchless sensitivity. They told of the mind expanding to infinity or dissolving into emptiness.

The humanist revolution caused modern Western culture to lose faith and interest in superior mental states, and to sanctify the mundane experiences of the average Joe. Modern Western culture is therefore unique in lacking a special class of people who seek to experience extraordinary mental states. It believes anyone attempting to do so is a drug addict, mental patient or charlatan. Consequently, though we have a detailed map of the mental landscape of Harvard psychology students, we know far less about the mental landscapes of Native American shamans, Buddhist monks or Sufi mystics. 2

And that is just the Sapiens mind. Fifty thousand years ago, we shared this planet with our Neanderthal cousins. They didn’t launch spaceships, build pyramids or establish empires. They obviously had very different mental abilities, and lacked many of our talents. Nevertheless, they had bigger brains than us Sapiens. What exactly did they do with all those neurons? We have absolutely no idea. But they might well have had many mental states that no Sapiens had ever experienced.

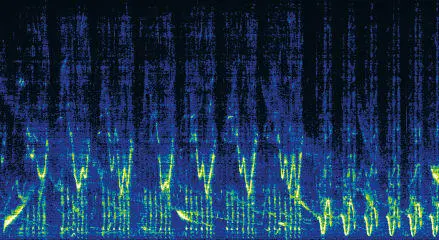

Yet even if we take into account all human species that ever existed, that would still not exhaust the mental spectrum. Other animals probably have experiences that we humans can barely imagine. Bats, for example, experience the world through echolocation. They emit a very rapid stream of high-frequency calls, well beyond the range of the human ear. They then detect and interpret the returning echoes to build a picture of the world. That picture is so detailed and accurate that the bats can fly quickly between trees and buildings, chase and capture moths and mosquitoes, and all the time evade owls and other predators.

The bats live in a world of echoes. Just as in the human world every object has a characteristic shape and colour, so in the bat world every object has its echo-pattern. A bat can tell the difference between a tasty moth species and a poisonous moth species by the different echoes returning from their slender wings. Some edible moth species try to protect themselves by evolving an echo-pattern similar to that of a poisonous species. Other moths have evolved an even more remarkable ability to deflect the waves of the bat radar, so that like stealth bombers they fly around without the bat knowing they are there. The world of echolocation is as complex and stormy as our familiar world of sound and sight, but we are completely oblivious to it.

One of the most important articles about the philosophy of mind is titled ‘What Is It Like to Be a Bat?’ 3In this 1974 article, the philosopher Thomas Nagel points out that a Sapiens mind cannot fathom the subjective world of a bat. We can write all the algorithms we want about the bat body, about bat echolocation systems and about bat neurons, but it won’t tell us how it feels to be a bat. How does it feel to echolocate a moth flapping its wings? Is it similar to seeing it, or is it something completely different?

Trying to explain to a Sapiens how it feels to echolocate a butterfly is probably as pointless as explaining to a blind mole how it feels to see a Caravaggio. It’s likely that bat emotions are also deeply influenced by the centrality of their echolocation sense. For Sapiens, love is red, envy is green and depression is blue. Who knows what echolocations colour the love of a female bat to her offspring, or the feelings of a male bat towards his rivals?

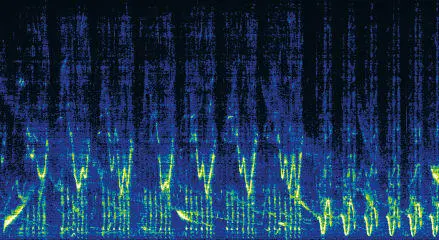

Bats aren’t special, of course. They are but one out of countless possible examples. Just as Sapiens cannot understand what it’s like to be a bat, we have similar difficulties understanding how it feels to be a whale, a tiger or a pelican. It certainly feels like something; but we don’t know like what. Both whales and humans process emotions in a part of the brain called the limbic system, yet the whale limbic system contains an entire additional part which is missing from the human structure. Maybe that part enables whales to experience extremely deep and complex emotions which are alien to us? Whales might also have astounding musical experiences which even Bach and Mozart couldn’t grasp. Whales can hear one another from hundreds of kilometres away, and each whale has a repertoire of characteristic ‘songs’ that may last for hours and follow very intricate patterns. Every now and then a whale composes a new hit, which other whales throughout the ocean adopt. Scientists routinely record these hits and analyse them with the help of computers, but can any human fathom these musical experiences and tell the difference between a whale Beethoven and a whale Justin Bieber? 4

A spectrogram of a bowhead whale song. How does a whale experience this song? The Voyager record included a whale song in addition to Beethoven, Bach and Chuck Berry. We can only hope it is a good one.

© Cornell Bioacoustics Research Program at the Lab of Ornithology.

None of this should surprise us. Sapiens don’t rule the world because they have deeper emotions or more complex musical experiences than other animals. So we may be inferior to whales, bats, tigers and pelicans at least in some emotional and experiential domains.

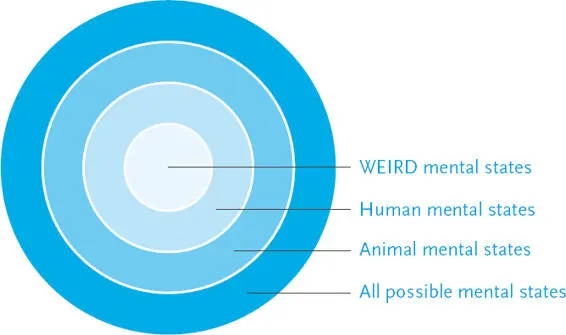

Beyond the mental spectrum of humans, bats, whales and all other animals, even vaster and stranger continents may lie in wait. In all probability, there is an infinite variety of mental states that no Sapiens, bat or dinosaur ever experienced in 4 billion years of terrestrial evolution, because they did not have the necessary faculties. In the future, however, powerful drugs, genetic engineering, electronic helmets and direct brain–computer interfaces may open passages to these places. Just as Columbus and Magellan sailed beyond the horizon to explore new islands and unknown continents, so we may one day set sail towards the antipodes of the mind.

The spectrum of consciousness.

I Smell Fear

As long as doctors, engineers and customers focused on healing mental diseases and enjoying life in WEIRD societies, the study of subnormal mental states and WEIRD minds was perhaps sufficient to our needs. Though normative psychology is often accused of mistreating any divergence from the norm, in the last century it has brought relief to countless people, saving the lives and sanity of millions.

However, at the beginning of the third millennium we face a completely different kind of challenge, as liberal humanism makes way for techno-humanism, and medicine is increasingly focused on upgrading the healthy rather than healing the sick. Doctors, engineers and customers no longer want merely to fix mental problems – they seek to upgrade the mind. We are acquiring the technical abilities to begin manufacturing new states of consciousness, yet we lack a map of these potential new territories. Since we are familiar mainly with the normative and sub-normative mental spectrum of WEIRD people, we don’t even know what destinations to aim towards.

Читать дальше

Конец ознакомительного отрывка

Купить книгу