In her New York Times article, Angelina Jolie referred to the high costs of genetic testing. At present, the test Jolie had taken costs $3,000 (which does not include the price of the actual mastectomy, the reconstruction surgery and related treatments). This in a world where 1 billion people earn less than $1 per day, and another 1.5 billion earn between $1 and $2 a day. 36Even if they work hard their entire life, they will never be able to finance a $3,000 genetic test. And the economic gaps are at present only increasing. As of early 2016, the sixty-two richest people in the world were worth as much as the poorest 3.6 billion people! Since the world’s population is about 7.2 billion, it means that these sixty-two billionaires together hold as much wealth as the entire bottom half of humankind. 37

The cost of DNA testing is likely to go down with time, but expensive new procedures are constantly being pioneered. So while old treatments will gradually come within reach of the masses, the elites will always remain a couple of steps ahead. Throughout history the rich enjoyed many social and political advantages, but there was never a huge biological gap separating them from the poor. Medieval aristocrats claimed that superior blue blood was flowing through their veins, and Hindu Brahmins insisted that they were naturally smarter than everyone else, but this was pure fiction. In the future, however, we may see real gaps in physical and cognitive abilities opening between an upgraded upper class and the rest of society.

When scientists are confronted with this scenario, their standard reply is that in the twentieth century too many medical breakthroughs began with the rich, but eventually benefited the whole population and helped to narrow rather than widen the social gaps. For example, vaccines and antibiotics at first profited mainly the upper classes in Western countries, but today they improve the lives of all humans everywhere.

However, the expectation that this process will be repeated in the twenty-first century may be just wishful thinking, for two important reasons. First, medicine is undergoing a tremendous conceptual revolution. Twentieth-century medicine aimed to heal the sick. Twenty-first-century medicine is increasingly aiming to upgrade the healthy. Healing the sick was an egalitarian project, because it assumed that there is a normative standard of physical and mental health that everyone can and should enjoy. If someone fell below the norm, it was the job of doctors to fix the problem and help him or her ‘be like everyone’. In contrast, upgrading the healthy is an elitist project, because it rejects the idea of a universal standard applicable to all, and seeks to give some individuals an edge over others. People want superior memories, above-average intelligence and first-class sexual abilities. If some form of upgrade becomes so cheap and common that everyone enjoys it, it will simply be considered the new baseline, which the next generation of treatments will strive to surpass.

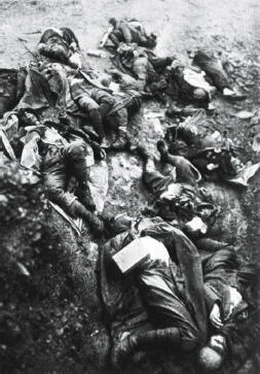

Second, twentieth-century medicine benefited the masses because the twentieth century was the age of the masses. Twentieth-century armies needed millions of healthy soldiers, and the economy needed millions of healthy workers. Consequently, states established public health services to ensure the health and vigour of everyone. Our greatest medical achievements were the provision of mass-hygiene facilities, the campaigns of mass vaccinations and the overcoming of mass epidemics. The Japanese elite in 1914 had a vested interest in vaccinating the poor and building hospitals and sewage systems in the slums, because if they wanted Japan to be a strong nation with a strong army and a strong economy, they needed many millions of healthy soldiers and workers.

But the age of the masses may be over, and with it the age of mass medicine. As human soldiers and workers give way to algorithms, at least some elites may conclude that there is no point in providing improved or even standard conditions of health for masses of useless poor people, and it is far more sensible to focus on upgrading a handful of superhumans beyond the norm.

Already today, the birth rate is falling in technologically advanced countries such as Japan and South Korea, where prodigious efforts are invested in the upbringing and education of fewer and fewer children – from whom more and more is expected. How could huge developing countries like India, Brazil or Nigeria hope to compete with Japan? These countries resemble a long train. The elites in the first-class carriages enjoy health care, education and income levels on a par with the most developed nations in the world. However, the hundreds of millions of ordinary citizens who crowd the third-class carriages still suffer from widespread diseases, ignorance and poverty. What would the Indian, Brazilian or Nigerian elites prefer to do in the coming century? Invest in fixing the problems of hundreds of millions of poor, or in upgrading a few million rich? Unlike in the twentieth century, when the elite had a stake in fixing the problems of the poor because they were militarily and economically vital, in the twenty-first century the most efficient (albeit ruthless) strategy may be to let go of the useless third-class carriages, and dash forward with the first class only. In order to compete with Japan, Brazil might need a handful of upgraded superhumans far more than millions of healthy ordinary workers.

How can liberal beliefs survive the appearance of superhumans with exceptional physical, emotional and intellectual abilities? What will happen if it turns out that such superhumans have fundamentally different experiences to normal Sapiens? What if superhumans are bored by novels about the experiences of lowly Sapiens thieves, whereas run-of-the-mill humans find soap operas about superhuman love affairs unintelligible?

The great human projects of the twentieth century – overcoming famine, plague and war – aimed to safeguard a universal norm of abundance, health and peace for all people without exception. The new projects of the twenty-first century – gaining immortality, bliss and divinity – also hope to serve the whole of humankind. However, because these projects aim at surpassing rather than safeguarding the norm, they may well result in the creation of a new superhuman caste that will abandon its liberal roots and treat normal humans no better than nineteenth-century Europeans treated Africans.

If scientific discoveries and technological developments split humankind into a mass of useless humans and a small elite of upgraded superhumans, or if authority shifts altogether away from human beings into the hands of highly intelligent algorithms, then liberalism will collapse. What new religions or ideologies might fill the resulting vacuum and guide the subsequent evolution of our godlike descendants?

10

The Ocean of Consciousness

The new religions are unlikely to emerge from the caves of Afghanistan or from the madrasas of the Middle East. Rather, they will emerge from research laboratories. Just as socialism took over the world by promising salvation through steam and electricity, so in the coming decades new techno-religions may conquer the world by promising salvation through algorithms and genes.

Despite all the talk of radical Islam and Christian fundamentalism, the most interesting place in the world from a religious perspective is not the Islamic State or the Bible Belt, but Silicon Valley. That’s where hi-tech gurus are brewing for us brave new religions that have little to do with God, and everything to do with technology. They promise all the old prizes – happiness, peace, prosperity and even eternal life – but here on earth with the help of technology, rather than after death with the help of celestial beings.

Читать дальше

Конец ознакомительного отрывка

Купить книгу