For politicians, business people and ordinary consumers, Dataism offers groundbreaking technologies and immense new powers. For scholars and intellectuals it also promises to provide the scientific holy grail that has eluded us for centuries: a single overarching theory that unifies all the scientific disciplines from literature and musicology to economics and biology. According to Dataism, King Lear and the flu virus are just two patterns of data flow that can be analysed using the same basic concepts and tools. This idea is extremely attractive. It gives all scientists a common language, builds bridges over academic rifts and easily exports insights across disciplinary borders. Musicologists, political scientists and cell biologists can finally understand each other.

In the process, Dataism inverts the traditional pyramid of learning. Hitherto, data was seen as only the first step in a long chain of intellectual activity. Humans were supposed to distil data into information, information into knowledge, and knowledge into wisdom. However, Dataists believe that humans can no longer cope with the immense flows of data, hence they cannot distil data into information, let alone into knowledge or wisdom. The work of processing data should therefore be entrusted to electronic algorithms, whose capacity far exceeds that of the human brain. In practice, this means that Dataists are sceptical about human knowledge and wisdom, and prefer to put their trust in Big Data and computer algorithms.

Dataism is most firmly entrenched in its two mother disciplines: computer science and biology. Of the two, biology is the more important. It was the biological embracement of Dataism that turned a limited breakthrough in computer science into a world-shattering cataclysm that may completely transform the very nature of life. You may not agree with the idea that organisms are algorithms, and that giraffes, tomatoes and human beings are just different methods for processing data. But you should know that this is current scientific dogma, and that it is changing our world beyond recognition.

Not only individual organisms are seen today as data-processing systems, but also entire societies such as beehives, bacteria colonies, forests and human cities. Economists increasingly interpret the economy, too, as a data-processing system. Laypeople believe that the economy consists of peasants growing wheat, workers manufacturing clothes, and customers buying bread and underpants. Yet experts see the economy as a mechanism for gathering data about desires and abilities, and turning this data into decisions.

According to this view, free-market capitalism and state-controlled communism aren’t competing ideologies, ethical creeds or political institutions. At bottom, they are competing data-processing systems. Capitalism uses distributed processing, whereas communism relies on centralised processing. Capitalism processes data by directly connecting all producers and consumers to one another, and allowing them to exchange information freely and make decisions independently. For example, how do you determine the price of bread in a free market? Well, every bakery may produce as much bread as it likes, and charge for it as much as it wants. The customers are equally free to buy as much bread as they can afford, or take their business to the competitor. It isn’t illegal to charge $1,000 for a baguette, but nobody is likely to buy it.

On a much grander scale, if investors predict increased demand for bread, they will buy shares of biotech firms that genetically engineer more prolific wheat strains. The inflow of capital will enable the firms to speed up their research, thereby providing more wheat faster, and averting bread shortages. Even if one biotech giant adopts a flawed theory and reaches an impasse, its more successful competitors will achieve the hoped-for breakthrough. Free-market capitalism thus distributes the work of analysing data and making decisions between many independent but interconnected processors. As the Austrian economics guru Friedrich Hayek explained, ‘In a system in which the knowledge of the relevant facts is dispersed among many people, prices can act to coordinate the separate actions of different people.’ 2

According to this view, the stock exchange is the fastest and most efficient data-processing system humankind has so far created. Everyone is welcome to join, if not directly then through their banks or pension funds. The stock exchange runs the global economy, and takes into account everything that happens all over the planet – and even beyond it. Prices are influenced by successful scientific experiments, by political scandals in Japan, by volcanic eruptions in Iceland and even by irregular activities on the surface of the sun. In order for the system to run smoothly, as much information as possible needs to flow as freely as possible. When millions of people throughout the world have access to all the relevant information, they determine the most accurate price of oil, of Hyundai shares and of Swedish government bonds by buying and selling them. It has been estimated that the stock exchange needs just fifteen minutes of trade to determine the influence of a New York Times headline on the prices of most shares. 3

Data-processing considerations also explain why capitalists favour lower taxes. Heavy taxation means that a large part of all available capital accumulates in one place – the state coffers – and consequently more and more decisions have to be made by a single processor, namely the government. This creates an overly centralised data-processing system. In extreme cases, when taxes are exceedingly high, almost all capital ends up in the government’s hands, and so the government alone calls the shots. It dictates the price of bread, the location of bakeries, and the research-and-development budget. In a free market, if one processor makes a wrong decision, others will be quick to utilise its mistake. However, when a single processor makes almost all the decisions, mistakes can be catastrophic.

This extreme situation in which all data is processed and all decisions are made by a single central processor is called communism. In a communist economy, people allegedly work according to their abilities, and receive according to their needs. In other words, the government takes 100 per cent of your profits, decides what you need and then supplies these needs. Though no country ever realised this scheme in its extreme form, the Soviet Union and its satellites came as close as they could. They abandoned the principle of distributed data processing, and switched to a model of centralised data processing. All information from throughout the Soviet Union flowed to a single location in Moscow, where all the important decisions were made. Producers and consumers could not communicate directly, and had to obey government orders.

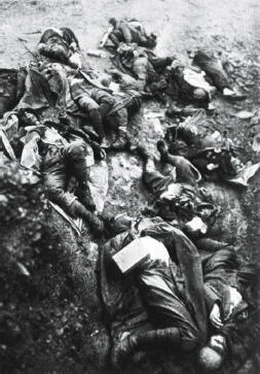

The Soviet leadership in Moscow, 1963: centralised data processing.

© ITAR-TASS Photo Agency/Alamy Stock Photo.

For instance, the Soviet economics ministry might decide that the price of bread in all shops should be exactly two roubles and four kopeks, that a particular kolkhoz in the Odessa oblast should switch from growing wheat to raising chickens, and that the Red October bakery in Moscow should produce 3.5 million loaves of bread per day, and not a single loaf more. Meanwhile the Soviet science ministry forced all Soviet biotech laboratories to adopt the theories of Trofim Lysenko – the infamous head of the Lenin Academy for Agricultural Sciences. Lysenko rejected the dominant genetic theories of his day. He insisted that if an organism acquired some new trait during its lifetime, this quality could pass directly to its descendants. This idea flew in the face of Darwinian orthodoxy, but it dovetailed nicely with communist educational principles. It implied that if you could train wheat plants to withstand cold weather, their progenies will also be cold-resistant. Lysenko accordingly sent billions of counter-revolutionary wheat plants to be re-educated in Siberia – and the Soviet Union was soon forced to import more and more flour from the United States. 4

Читать дальше

Конец ознакомительного отрывка

Купить книгу