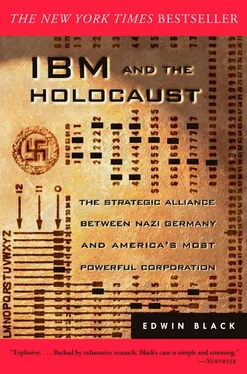

II. THE IBM – HITLER INTERSECTION

ON JANUARY 30, 1933, THE WORLD AWOKE TO A FRIGHTENINGnew reality: Adolf Hitler had suddenly become leader of Ger many. Hitlerites dressed in a spectrum of uniforms from gauche to ominous, paraded, motored, and bicycled through Berlin in defiant celebration. Hanging from trucks and stomping through the squares, arms outstretched and often swaggering in song, the Nazis were jubilant. Their historic moment—fraught with emotional expectations of revenge and victory against all adversaries—their long awaited decisive moment had arrived. From this instant, the world would never be the same.

Quickly, Hitler’s Nazis moved to take over the entire government and virtually all aspects of German commerce, society, and culture. Der Fuhrer wanted an Aryan Germany to dominate all of Europe with a master race subjugating all non-Aryans. For Jews, Hitler had a special plan: total destruction. There were no secrets in Hitler’s vision. He broadcast them loudly to the world. They exploded as front-page headlines in every major city, on every radio network, and in weekly cinema newsreels. Ironically, Hitler’s fascism resonated with certain men of great vision, such as Henry Ford. Another who found Hitlerism compelling was Thomas J. Watson, president of one of America’s most prestigious companies: Inter national Business Machines. 1

The roads traveled by Hitler and Watson began in different parts of the world in completely different circumstances with completely different intentions. How did these two men—one an extreme capitalist, the other an extreme fascist—form a technologic and commercial alliance that would ultimately facilitate the murder of six million Jews and an equal number of other Europeans? These men and their philosophies could not have been more dissimilar. Yet as history proved, they could have hardly been more compatible.

It all began decades before in New York during the last gasp of the nineteenth century, at a time when America’s rapid industrial growth spurred inventions to automate virtually every manual task. Swells of immigrants came to American shores to labor long days. But some dreamed of a better way to be industrious—or at least a faster and cheaper way. Contraptions, mechanizations, and patented gadgets were everywhere turning wheels, cranking cogs, and saving steps in workshops and factories. The so-called Second Industrial Revolution, powered by electricity, was in full swing. Turn-of-the-century America—a confluence of massive commerce and clickety-clack industrial ingenuity—was a perfect moment for the birthplace of the most powerful corporation the world has ever seen: IBM. 2

IBM’s technology was originally created for only one reason: to count people as they had never been counted before, with a magical ability to identify and quantify. Before long, IBM technology demonstrated it could do more than just count people or things. It could compute, that is, the technology could record data, process it, retrieve it, analyze it, and automatically answer pointed questions. Moments of mechanized bustle could now accomplish what would be an impossibility of paper and pencil calculation for any mortal man.

Herman Hollerith invented IBM. Born in 1860, Hollerith was the son of intellectual German parents who brought their proud and austere German heritage with them when they settled in Buffalo, New York. Herman was only seven when his father, a language teacher, died in an accident while riding a horse. His mother was left to raise five children alone. Proud and independent, she declined to ask her financially comfortable parents for assistance, choosing instead a life of tough, principled self-reliance. 3

Young Hollerith moved to New York City when, at age fifteen, he enrolled in the College of the City of New York. Except for spelling difficulties, he immediately showed a creative aptitude, and at age nineteen graduated from the Columbia School of Mines with a degree in engineering, boasting perfect 10.0 grades. In 1879, Hollerith accepted the invitation of his Columbia professor to become an assistant in the U.S. Census Bureau. In those days, the decennial census was little more than a basic head-count, devoid of information about an individual’s occupation, education, or other traits because the computational challenge of counting millions of Americans was simply too prodigious. As it was, the manual counting and cross-tabulation process required several years before final results could be tallied. Because the post-Civil War populace had grown so swiftly, perhaps doubling since the last census, experts predicted spending more than a decade to count the 1890 census; in other words, the next census in 1900 would be underway before the previous one was complete. 4

Just nineteen years old, Hollerith moved to Washington, D.C., to join the Census Bureau. Over dinner one night at the posh Potomac Boat Club, Director of Vital Statistics, John Billings, quipped to Hollerith, “There ought to be a machine for doing the purely mechanical work of tabulating population and similar statistics.” Inventive Hollerith began to think about a solution. French looms, simple music boxes, and player pianos used punched holes on rolls or cards to automate rote activity. About a year later, Hollerith was struck with his idea. He saw a train conductor punch tickets in a special pattern to record physical characteristics such as height, hair color, size of nose, and clothing—a sort of “punched photograph.” Other conductors could read the code and then catch anyone re-using the ticket of the original passenger. 5

Hollerith’s idea was a card with standardized holes, each representing a different trait: gender, nationality, occupation, and so forth. The card would then be fed into a “reader.” By virtue of easily adjustable spring mechanisms and brief electrical brush contacts sensing for the holes, the cards could be “read” as they raced through a mechanical feeder. The processed cards could then be sorted into stacks based on a specified series of punched holes. 6

Millions of cards could be sorted and resorted. Any desired trait could be isolated—general or specific—by simply sorting and resorting for data-specific holes. The machines could render the portrait of an entire population—or could pick out any group within that population. Indeed, one man could be identified from among millions if enough holes could be punched into a card and sorted enough times. Every punch card would become an informational storehouse limited only by the number of holes. It was nothing less than a nineteenth-century bar code for human beings. 7

By 1884, a prototype was constructed. After borrowing a few thousand dollars from a German friend, Hollerith patented and built a production machine. Ironically, the initial test was not a count of the living, but of the dead for local health departments in Maryland, New York, and New Jersey. 8

Soon, Hollerith found his system could do more than count people. It could rapidly perform the most tedious accounting functions for any enterprise: from freight bills for the New York Central Railroad to actuarial and financial records for Prudential Insurance. Most importantly, the Hollerith system not only counted, it produced analysis. The clanging contraption could calculate in a few weeks the results that a man previously spent years correlating. Buoyed by success, Hollerith organized a trip overseas to show his electromechanical tabulator to European governments, including Germany and Italy. Everywhere Hollerith was met with acclaim from bureaucrats, engineers, and statisticians. 9His card sorter was more than just a clever gadget. It was a steel, spindle, and rubber-wheeled key to the Pandora’s Box of unlimited information.

When the U.S. Census Bureau sponsored a contest seeking the best automated counting device for its 1890 census, it was no surprise when Hollerith’s design won. The judges had been studying it for years. Hollerith quickly manufactured his first machines. 10

Читать дальше