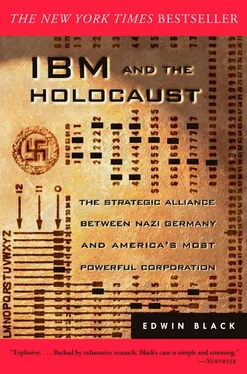

What made me demand answers to the unasked questions about IBM and the Holocaust? I confronted the reality of IBM’s involvement one day in 1993 in Washington at the United States Holocaust Museum. There, in the very first exhibit, an IBM Hollerith D-11 card sorting machine—riddled with circuits, slots, and wires—was prominently displayed. Clearly affixed to the machine’s front panel glistened an IBM nameplate. It has since been replaced with a smaller IBM machine because so many people congregated around it, creating a bottleneck. The exhibit explained little more than that IBM was responsible for organizing the census of 1933 that first identified the Jews. IBM had been tight-lipped about its involvement with Nazi Germany. So although 15 million people, including most major Holocaust experts, have seen the display, and in spite of the best efforts of leading Museum historians, little more was understood about this provocative display other than the brief curator’s description at the exhibit and a few pages of supportive research.

I still remember staring at the machine for an hour, and the moment when I turned to my mother and father who accompanied me to the museum that day and promised them I would discover more.

My parents are Holocaust survivors, uprooted from their homes in Poland. My mother escaped from a boxcar en route to Treblinka, was shot, and then buried in a shallow mass grave. My father had already run away from a guarded line of Jews and discovered her leg protruding from the snow. By moonlight and by courage, these two escapees survived against the cold, the hunger, and the Reich. Standing next to me five decades later, their image within the reflection of the exhibit glass, shrapnel and bullet fragments permanently embedded in their bodies, my parents could only express confusion.

But I had other questions. The Nazis had my parents’ names. How?

What was the connection of this gleaming black, beige, and silver machine, squatting silently in this dimly lit museum, to the millions of Jews and other Europeans who were murdered—and murdered not just in a chaotic split-second as a casualty of war, but in a grotesque and protracted twelve-year campaign of highly organized humiliation, dehumanization, and then ultimately extermination.

For years after that chance discovery, I was shadowed by the realization that IBM was somehow involved in the Holocaust in technologic ways that had not yet been pieced together. Dots were everywhere. The dots needed to be connected.

Knowing that International Business Machines has always billed itself as a “solutions” company, I understood that IBM does not merely wait for governmental customers to call. IBM has amassed its fortune and reputation precisely because it generally anticipates governmental and corporate needs even before they develop, and then offers, designs, and delivers customized solutions—even if it must execute those technologic solutions with its own staff and equipment. IBM has done so for countless government agencies, corporate giants, and industrial associations.

For years I promised myself I would one day answer the question: How many solutions did IBM provide to Nazi Germany? I knew about the initial solution: the census. Just how far did the solutions go?

In 1998, I began an obsessive quest for answers. Proceeding without any foundation funds, organizational grants, or publisher dollars behind me, I began recruiting a team of researchers, interns, translators, and assistants, all on my own dime.

Soon a network developed throughout the United States, as well as in Germany, Israel, England, Holland, Poland, and France. This network continued to grow as time went on. Holocaust survivors, children of survivors, retirees, and students with no connection to the Holocaust—as well as professional researchers, distinguished archivists and historians, and even former Nuremberg Trial investigators—all began a search for documentation. Ultimately, more than 100 people participated, some for months at a time, some for just a few hours searching obscure Polish documents for key phrases. Not knowing the story, they searched for key words: census, statistics, lists, registrations, railroads, punch cards, and a roster of other topics. When they found them, the material was copied and sent. For many weeks, documents were flowing in at the rate of 100 per day.

Most of my team was volunteers. All of them were sworn to secrecy. Each was shocked and saddened by the implications of the project and intensely motivated. A few said they could not sleep well for days after learning of the connection. I was often sustained by their words of encouragement.

Ultimately, I assembled more than 20,000 pages of documentation from fifty archives, library manuscript collections, museum files, and other repositories. In the process, I accessed thousands of formerly classified State Department, OSS, or other previously restricted government papers. Other obscure documents from European holdings had never been translated or connected to such an inquiry. All these were organized in my own central archive mir-roring the original archival source files. We also scanned and translated more than fifty general books and memoirs, as well as contemporary technical and scientific journals covering punch cards and statistics, Nazi publications, and newspapers of the era. All of this material—primary documents, journal articles, newsclips, and book extracts—were cross-indexed by month. We created one manila folder for every month from 1933 to 1950. If a document referred to numerous dates, it was cross-filed in the numerous monthly folders. Then all contents of monthly folders were further cross-indexed into narrow topic threads, such as Warsaw Ghetto, German Census, Bulgarian Railroads, Watson in Germany, Auschwitz, and so on.

Stacks of documents organized into topics were arrayed across my basement floor. As many as six people at a time busily shuttled copies of documents from one topic stack to another from morning until midnight. One document might be copied into five or six topic stacks. A high-speed copier with a twenty-bin sorter was installed. Just moving from place to place in the basement involved hopscotching around document piles.

None of the 20,000 documents were flash cards. It was much more complex. Examined singly, none revealed their story. Indeed, most of them were profoundly misleading as stand-alone papers. They only assumed their true meaning when juxtaposed with numerous other related documents, often from totally unrelated sources. In other words, the documents were all puzzle pieces—the picture could not be constructed until all the fragments were put together. For example, one IBM report fleetingly referred to a “Mr. Hendricks” as fetching an IBM machine from Dachau. Not until I juxtaposed that document with an obscure military statistics report discovered at the Public Record Office in London did I learn who Sgt. Hendricks really was.

Complicating the task, many of the IBM papers and notes were unsigned or undated carbons, employing deliberate vagueness, code words, catchphrases, or transient corporate shorthand. I had to learn the contemporaneous lexicon of the company to decipher their content. I would study and stare at some individual documents for months until their meaning finally became clear through some other discovered document. For example, I encountered an IBM reference to accumulating “points.” Eventually, I discovered that “points” referred to making sales quotas for inclusion in IBM’s Hundred Percent Club. IBM maintained sales quotas for all its subsidiaries during the Hitler era.

Sometimes a key revelation did not occur until we tracked a source back three and four stages. For example, I reviewed the English version of the well-known volume Destruction of the Dutch Jews by Jacob Presser. I found nothing on my subject. I then asked my researchers in Holland to check the Dutch edition. They found a single unfootnoted reference to a punch card system. Only by checking Presser’s original typescript did we discover a marginal notation that referenced a Dutch archival document that led to a cascade of information on the Netherlands. In reviewing the Romanian census, I commissioned the translation of a German statistician’s twenty-page memoir to discover a single sentence confirming that punch cards were used in Romania. That information was juxtaposed against an IBM letter confirming the company was moving machinery from war-torn Poland into Romania to aid Romanian census operations.

Читать дальше