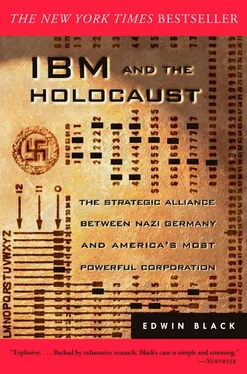

Despondent and unapproachable for months during the self-inflicted Census Bureau debacle, Hollerith refused to deal with an onslaught of additional bad business news. Strategic investments porously lost money. Several key railroad clients defected. Tabulating Machine Company did, however, rebound with new designs, improved technology, more commercial clients, and more foreign census contracts. But then, in 1910, in an unbelievably arrogant maneuver, Hollerith actually tried to stop the United States from exercising its constitutionally mandated duty to conduct the census. Claiming the Census Bureau was about to deploy new machinery that in some way infringed his patents, Hollerith filed suit and somehow convinced a federal judge in Washington, D.C., to issue a restraining order against the Thirteenth Census. But the courts eventually ruled against Tabulating Machine Company. Hollerith had lost big. 24

Continuing in denial, the wealthy Hollerith tinkered with new contrap-tions and delved into unrelated diversions while his company floundered. His doctors insisted it was time to leave the business. Frustrated stockholders and management of Tabulating Machine Company welcomed that advice and encouraged Hollerith to retire. Ambivalently, Hollerith began parceling out his interests. 25

He began with Germany. In 1910, the inventor licensed all his patents to a German adding machine salesman named Willy Heidinger. Heidinger created the firm Deutsche Hollerith Maschinen Gesellschaft—the German Hollerith Machine Corporation, or Dehomag for short. This firm was owned and controlled by Heidinger; only a few of his relatives owned token shares. As a licensee of Tabulating Machine Company, Dehomag simply leased Hollerith technology in Germany. Tabulating Ma chine Company received a share of Dehomag’s business, plus patent royalties. Heidinger was a traditional German, fiercely proud of his heritage, and dedicated to his family. Like Hollerith, Heidinger was temperamental, prone to volcanic outbursts, and always ready for corporate combat. 26

The next year, a disillusioned, embittered Hollerith simply sold out completely. Enter Charles Flint, a rugged individualist who at the edge of the nineteenth century epitomized the affluent adventurer capitalist. One of the first Americans to own an automobile and fly an aeroplane, an avid hunter and fisherman, Flint made his millions trading in international commodities. Weapons were one of those commodities and Flint didn’t care whom he sold them to. 27

Flint’s war profiteering knew no limits. He organized a private armada to help Brazilian officials brutally suppress a revolt by that nation’s navy, thus restoring the government’s authority. He licensed the manufacture of the newly invented Wright Brothers aeroplane to Kaiser Wilhelm to help launch German military aviation and its Great War aces. Indeed, Flint would happily sell guns and naval vessels to both sides of a brutal war. He sold to Peru just after leaving the employ of Chile when a border skirmish between them erupted, and to enemies Japan and Russia during their various conflicts. 28

Of Flint it was once written, “Had anyone called him a merchant of death, Flint would have wondered what the fellow had in mind. Such was the nature of the Western World prior to the Great War.” 29

Flint had also perfected an infamous business modality, the so-called trust . Trusts were the anti-competitive industrial combinations that often secretly devoured competition and ultimately led to a government crack-down. The famous Sherman Anti-Trust Act was created just to combat such abuses. Newspapers of the day dubbed Flint, the “father of trusts.” The title made him at once a glamorous legend and a villain in his era. 30

In 1911, the famous industrial combine maestro, who had so deftly created cartel-like entities in the rubber and chemical fields, now tried something different. He approached key stockholders and management of four completely unrelated manufacturing firms to create one minor diversified conglomerate. The centerpiece would be Hollerith’s enterprise. 31

The four lackluster firms Flint selected defied any apparent rationale for merger. International Time Recording Company manufactured time clocks to record worker hours. Computing Scale Company sold simple retail scales with pricing charts attached as well as a line of meat and cheese slicers. Bundy Manufacturing produced small key-actuated time clocks, but, more importantly, it owned prime real estate in Endicott, New York. Of the four, Hollerith’s Tabulating Machine Company was simply the largest and most dominant member of the group. 32

Hollerith agreed to the sale, offering his stock for about $1.21 million, plus a 10-year consulting contract at $20,000 per year—an enormous sum for its day. The resulting company was given a prosaic name arising from its strange combination: Computing-Tabulating-Recording Company, or CTR. The new entity was partially explained by some as a synergistic combine that would bring ready cash and an international sales force to four seemingly viable companies stunted by limited growth potential or troubled economics. Rather than bigness, Flint wanted product mix that would make each of the flagging partners stronger. 33

After the sale was finalized, a seemingly detached Hollerith strolled over to his Georgetown workshop, jammed with stacked machine parts in every corner, and declared to the workers matter-of-factly: “Well, I sold the business.” Approaching the men individually, Hollerith offered one curt comment or another. He was gracious to Bill Barnes, who had lost an arm while assembling a belt mechanism. For Joe, a young shop worker, Hollerith ostentatiously handed him a $50 bill, making quite an impression on someone who had never seen so large a bill. 34

Hollerith withdrew as an active manager. 35The commercial extension of his ingenuity and turbulent persona was now in the hands of a more skilled supranational manipulator, Charles Flint. Hollerith was willing to make millions, but only on his terms. Flint wanted millions—on any terms. Moreover, Flint wanted CTR’s helm to be captained by a businessman, not a technocrat. For that, he chose one of America’s up and coming business scoundrels, Thomas J. Watson.

* * *

CARVED AMONGthe densely wooded hills, winding, dusty back roads connected even the remotest farm to the small villages and towns that comprised the Finger Lakes region of New York State in the 1890s. Gray and rutted, crackling from burnt orange maple leaves in the fall and yielding short clouds of dust in the summer beneath the hoof and wheel of Thomas J. Watson’s bright yellow horse-drawn organ wagon, these lonely yet intriguing by-ways seemed almost magical. Pastoral vistas of folding green hills veined with streams lay beyond every bend and dip. But even more alluring was the sheer adventure of selling that awaited Watson. Back then, it was just pianos and sewing machines. 36But it took all-day tenacity and unending self-confidence to travel these dirt roads just for the opportunity—not the certainty, only the opportunity—to make a sale.

Yet “making the sale,” that calculating one-on-one wizardry that ends as an exhilarating confirmation of one’s mind over another’s motivation, this was the finesse—the power—that came naturally to Watson. Tall, lanky, handsome, and intelligent, he understood people. He knew when to listen and when to speak. He had mastered the art of persuasion and possessed an uncanny ability to overcome intense opposition and “close the deal.”

All born salesmen know that the addicting excitement of a sales victory is short-lived. No matter how great the sale, it is never enough. Selling, for such people, becomes not an occupation, but a lifestyle.

Any salesman can sell anything. Every salesman alive knows these words are true. But they also know that not all salesmen can go further. Few of them can conquer.

Читать дальше