Getting a bomb near Hitler proved to be far more difficult than originally Imagined, The Führer was growing increasingly distrustful and solitary, he seldom left his headquarters and then often altered his travel plans without warning. Arrangements were made for him to visit Field Marshal Weichs’s army group in Poltava, where a group of officers was also prepared to overpower him; he abruptly changed his route, however, and flew instead to Saporoshe. There, ironically, he barely escaped an attacking Russian tank unit that had run out of fuel at the edge of his landing field.

After turning down a number of requests, Hitler finally agreed to visit Army Group Center in Smolensk in the early morning of March 13, 1943, on his way from his headquarters in Vinnitsa back to Rastenburg. Shortly before the three aircraft carrying the Führer, his staff, and the SS escort touched down, Kluge suddenly sensed something and turned to Tresckow, saying, “For heaven’s sake, don’t do anything today! It’s still too soon for that!” 34In fact, Tresckow, believing that the most opportune time had already passed with the battle of Stalingrad that winter, had taken the precaution of developing a number of assassination plans simultaneously. One of them called for a bomb to be placed in Hitler’s parked vehicle during the visit, but all attempts to slip through the phalanx of SS men to reach the car failed. A second plot was to be carried out if possible by Georg von Boeselager, who had begun assembling a unit near Army Group Center for use in the impending coup. Tresckow was apparently prepared to ignore Kluge’s concerns-so long as there was some assurance that the field marshal himself would not be put in danger-and had positioned Boeselager’s officers and soldiers near Hitler’s SS units as additional “security.” In reality, it seems that they were supposed to open fire on Hitler if an opportunity presented itself. 35

After a briefing in Kluge’s barracks, Hitler’s party headed for the nearby officers’ mess. As one witness described the scene, Hitler was sitting with his head hunched over his plate, shoveling in his vegetables, when Tresckow turned to Lieutenant Colonel Heinz Brandt, who was seated next to him, and asked if he minded taking two bottles of Cointreau back to headquarters on the flight. When Brandt readily agreed, Tresckow explained that they were part of a bet he’d made with Colonel Stieff and that Schlabrendorff would hand over the package at the airfield. When the visitors left shortly thereafter, Hitler not only took a different route than previously arranged, but also invited Kluge to ride in his car, thus ruling out any further action at this point. Meanwhile, Schlabrendorff sent Berlin the code word signaling the beginning of the operation and drove off after the column of vehicles.

At the airfield he waited until Hitler had boarded one of three waiting planes, then squeezed the acid detonator and handed the package to Brandt. The bomb was set to go off in thirty minutes, and since the planes took off immediately, Schlabrendorff and Tresckow calculated that the explosion would occur just before Minsk. They returned to headquarters and waited for news of the Führer’s plane from one of its fighter escorts. But nothing happened. Having carried out countless test explosions during the previous weeks, not one of which had failed they were certain of success. But now two hours passed and still there was no word. The conspirators were waiting with mounting anxiety when a message finally arrived from Hitler’s headquarters: the Führer and his escorts had arrived safely in Rastenburg.

The reasons for the failure of the assassination attempt of March 13, 1943, have never been fully clarified. The major problem immediately facing the conspirators, however, was how to undo their plan and recover the package before an accident occurred or the contents were discovered. Tresckow decided to telephone Brandt. Coolly he asked him to hold on to the package-there had been an unfortunate mix-up. Schlabrendorff would come the next day on the daily courier flight to Rastenburg and exchange it for the right one.

Fortunately, Brandt still had the original package the next morning when Schlabrendorff arrived, and the exchange was made. Schlabrendorff headed for the waiting train, which was to take him to Berlin that evening. Once in a closed compartment, he opened the bomb with a razor blade and removed the detonator. He found that the capsule had broken, the acid had eaten its way through the wire holding the firing pin, the firing pin had struck as intended, and even the percussion cap seemed to have ignited. But the explosive had not gone off. Among the theories that have been advanced to explain this mystery, the most likely is that the heater in the plane’s cargo hold had malfunctioned, as it sometimes did, and the explosive, which was sensitive to cold, failed to ignite as a result. The most promising assassination plot of the war years had come to naught. 36

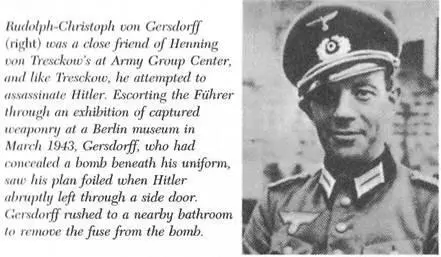

Schlabrendorff and Tresckow were “shattered” by the inexplicable outcome of their attempt on Hitler’s life, for which they had run so many risks and spent so much time laying secret plans. Tresckow refused, however, to allow himself to grow despondent, nor did he following the failures that were still to come. Typically for him, he did not waste a single second bemoaning his ill fortune, and when another opportunity happened to fall into his lap just a few days later he seized it. News arrived from Führer headquarters that “Heroes’ Memorial Day” would be celebrated on March 21 and that, after attending a service in the glass-roofed hall of the Berlin Zeughaus, Hitler wanted to visit the exhibition of captured enemy weaponry in the same building. Since Army Group Center had arranged the exhibition, Hitler expressly requested the attendance of Field Marshal Kluge.

It was much more important to Tresckow that Gersdorff be there, and since it was Tresckow’s department that had actually put the exhibition together, he had a perfect pretext to seek an invitation for the staff intelligence officer. Gersdorff was immediately summoned back to army group headquarters. When he appeared, Tresckow spoke “with the utmost gravity” about the situation and the “absolute necessity” of saving Germany from destruction. Then he abruptly broached the question of whether Gersdorff would undertake an assassination attempt in which he would probably be blown up himself. 37Gersdorff reflected briefly and agreed. Schlabrendorff was asked to remain in Berlin and turn over to Gersdorff the bombs he still had from the assassination attempt of March 13.

But from this point on, the plot-as promising as it seemed- would be plagued by misfortune. At first, Brigadier General Rudolf Schmundt, Hitler’s increasingly suspicious chief aide, refused to allow Gersdorff to take part in the visit or even know when the ceremonies were scheduled to begin (as Hitler’s inner circle was constantly reminded, the divulgence of such information was punishable by death). Then Kluge had to be persuaded not to go to Berlin, even though he had been invited by Hitler himself, because Tresckow wanted lo keep him away from the assassination. Furthermore, when the explosive was turned over to Gersdorff, he learned that in the rush of events the usual short fuses could not be procured. Oster was asked lo help but could do nothing, so Gersdorff was forced to rely on the ten-minute fuses he had brought along just in case.

The memorial service began an hour later than scheduled. After making a short address Hitler walked over to the exhibition with Göring, Himmler, Donitz, and Keitel. Waiting at the entrance were Gersdorff, Field Marshal Walter Model, acting as Kluge’s representative, and a uniformed director of the museum. Gersdorff ignited the disc when he saw the Führer approach and kept close to his side as the Führer went through the exhibition. But Hitler paid scarcely any attention to the explanations Gersdorff wanted to provide about the objects on display. Nervously, as if scenting danger, he hurried through the rooms. Even a standard from the Napoleonic Wars that German engineers had uncovered in the riverbed of the Berezina failed to capture his attention. About two minutes after entering the exhibition, as a radio broadcast reported, Hitler abruptly left through a side door by the chestnut grove on Unter den Linden. Here, outside the building, he finally discovered a captured Soviet tank and was so fascinated by it that he spent considerable time clambering around on it. In the meantime Gersdorff had rushed to the nearest washroom, where he ripped the fuse out of the bomb. To catch his breath he went to the Union Club where he ran into the Cologne banker Waldemar von Oppenheim, who blithely related that he had just been in a position to kill Hitler as the Führer “drove very slowly in an open ear down the Linden right in front of my ground-floor room in the Hotel Bristol. It would have been child’s play to heave a hand grenade over the sidewalk and into his car.” 38

Читать дальше

![Traudl Junge - Hitler's Last Secretary - A Firsthand Account of Life with Hitler [aka Until the Final Hour]](/books/416681/traudl-junge-hitler-s-last-secretary-a-firsthand-thumb.webp)