As a result of the massacres in the East, relations between Hitler and the officer corps, which had always been cool, despite a momentary reconciliation at the time of the great triumphs in France, began to deteriorate rapidly. “By nature I belong to an entirely different genus,” Hitler had once said-and the feeling was mutual. 16Hitler’s speech to the assembled officers on March 30 and the subsequent orders putting his message into legal language had conclusively refuted the belief that Nazi excesses were the work of “lower-level authorities” carrying on behind Hitler’s back, a misapprehension that had long inhibited action. Now the resistance gathered strong new support. Yorck showed up at Army Group Center headquarters passionately voicing his anger; Gersdorff finally overcame his lingering abhorrence of treason; Stieff turned away from the regime, sickened by what was happening. And it was apparently at this time, too, that Stauffenberg resolved to do everything in his power to remove Hitler and overthrow the regime. 17The biographies of several members of the resistance, especially the younger conspirators, show just how crucial the horrendous crimes in the East were in motivating them to act.

Differences of opinion over military operations soon erupted between Hitler and his army commanders, exacerbating the latent tensions that already existed. German units had succeeded, to be sure, in slicing deep into the Soviet Union and running up an impressive series of victories. Yet it was becoming increasingly apparent that each triumph only carried them further and further into the endless expanses of the Soviet Union, while the front was becoming more and more disjointed.

Attention therefore turned to how the army could use its available forces most effectively. Whereas the OKH and Army Group Center advocated a concentrated assault on Moscow, Hitler insisted on “pushing through the Ukraine into the Caucasus” and beyond to the oil fields of the Caspian Sea and Persian Gulf. At the same time he ordered the troops to advance in the north so as to cut the enemy off from the Baltic Sea. The fractious dispute that ensued did not revolve around two rival strategies so much as around one strategy and one fantasy, consisting of Hitler’s faith in his own invincibility, concern about increasingly noticeable shortages of goods and raw materials, and an unrestrained lust for land. By August 1941 general staff officers were already muttering about Hitler’s “bloody amateurism.” 18

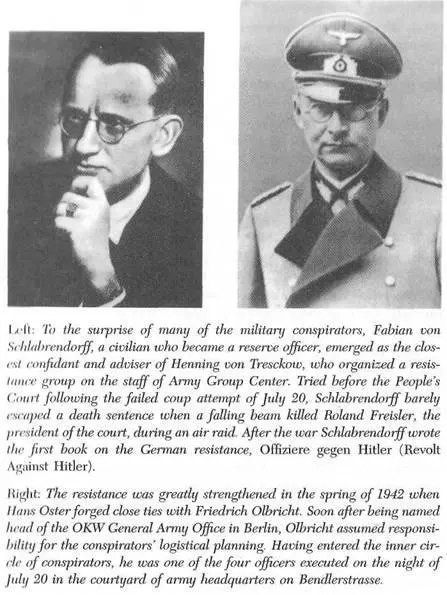

After a long spell in the doldrums the resistance was buoyed by rapidly spreading rumors about the tensions in Hitler’s headquarters. In the early autumn General Georg Thomas visited the army groups to assess their willingness to take action. He learned that the swift advance through the Soviet Union and the unease it was creating in the various headquarters prevented any serious planning for a coup. The idea of striking from France with Witzleben’s help was raised briefly but soon dropped. In late September Tresckow decided to send Fabian von Schlabrendorff to Berlin to let the circle around Ludwig Beck know that Army Group Center was “prepared to do anything” if a coup was launched. There is no doubt that this message vastly exaggerated current sentiments in the army group and was more an expression of the sense of mounting exasperation in the face of the increasingly pointed conflict between honor and obedience, the oath of allegiance and the barbarous methods of war. Schlabrendorff conferred in Berlin with Hassell, who noted in his diary the one truly notable feature of Tresckow’s project: for the first time in the history of the resistance “an initiative of sorts” for overthrowing the regime had come from the army rather than the civilian opposition. 19

A few days later General Thomas and General Alexander von Falkenhausen, the military commander in Belgium and northern France, went to see Brauchitsch. They both found him surprisingly receptive to their ideas, probably not least because he was exhausted from the interminable wrangling with Hitler. According to an entry in Hassell’s diary, Brauchitsch acknowledged “what a bloody mess everything had become and even came to see that he himself must be held partially responsible.” 20As if a signal had gone out, activity within opposition circles immediately picked up. At meeting after meeting, “the overall situation was discussed,” Hassell recorded, “just in case…” Other preparatory steps were taken as well: ties were established with Trott, Yorck, and Moltke, and Hassell was requested shortly thereafter to visit Witzleben and Falkenhausen. After the somber mood of the previous months, spirits within the opposition finally began to lift. Tresckow even felt sufficiently encouraged to make a last, although ultimately futile, attempt to draw Bock into the resistance.

At this point the great Russian winter descended on the troops in the field, who were left without appropriate provisions, having charged ahead on the assumption that there would be “no winter campaign,” as Hitler had assured skeptics only shortly before. The German offensive literally froze in its tracks, and confusion spread across the front. With every ounce of the general staffs strength devoted to dealing with the situation of the troops, all planning for a coup ceased. The members of the resistance fell once again into such despondency that they even interpreted Hitler’s dismissal of Brauchitsch on December 19-undertaken in the hope of ending the festering conflict with the OKH-as a blow. The incessant swinging from high to low had so frazzled them that the few strong words Brauchitsch had spoken to Thomas and Falkenhausen had raised their hopes in him, making them forget the countless occasions when he had demonstrated his lack of courage and sown nothing but despair. Hassell gave the figures who appeared in his diary humorously appropriate aliases, and it was no accident that Brauchitsch’s moniker was “Pappenheim,” which means a habitually unreliable person.

As he had done in the past, Hitler attempted to solve his problems with the army by assuming supreme command after Brauchitsch’s dismissal, thus making himself answerable only to himself twice over. The reasons he gave for this step are equally revelatory of his arrogance and his suspicion, as well as of his desire to bring about the ideological radicalization of the army, which had remained noticeably cool to his ideas. “Anybody can handle operational leadership-that’s easy,” he said. “The task of the commander in chief of the army is to give the army National Socialist training; I know no general of the army who could perform this task as I would have it.” 21Hitler used Brauchitsch’s departure as an opportunity to clean house in the upper echelons of the army. A large number of generals and division commanders were ousted, and Bock was replaced as commander in chief of Army Group Center by Field Marshal Hans Günther von Kluge. Relieving Gerd von Rundstedt of command of Army Group South, Hitler installed Field Marshal Walther von Reichenau. For failure to comply with orders to stand firm during the winter crisis, General Heinz Guderian was dismissed and General Erich Hoepner expelled from the army entirely. The commander in chief of Army Group North, Field Marshal Wilhelm von Leeb, resigned voluntarily.

But Hitler’s nervous interventions and the insults and abuse he heaped on his generals could do nothing to dispel the specter of defeat that suddenly hung over the German forces. After striding for almost twenty years from one political, diplomatic, or military triumph to the next, Hitler suffered his first serious setback in the winter of 1941-2. The aura of invincibility that had surrounded Hitler and his armies, keeping them together and holding uncertainty at bay, began to dissipate. Always a gambler, Hitler had bet everything on a single card, and with the defeat before the gates of Moscow, his entire plan collapsed. The blitzkrieg had failed, as he immediately realized, and with it his whole strategy for the war against the Soviet Union.

Читать дальше

![Traudl Junge - Hitler's Last Secretary - A Firsthand Account of Life with Hitler [aka Until the Final Hour]](/books/416681/traudl-junge-hitler-s-last-secretary-a-firsthand-thumb.webp)