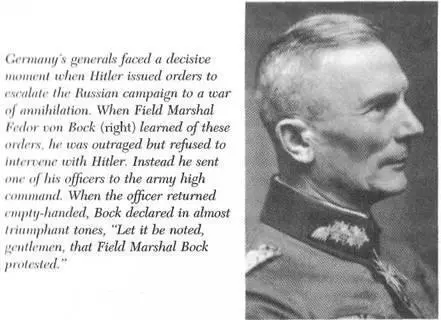

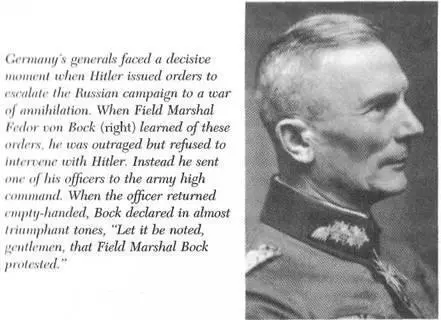

After reflecting for a while Bock decided despite Tresckow’s constant objections to send Gersdorff to OKH (Army) headquarters in Berlin with the message that Field Marshal Bock vehemently protested the orders and demanded that they be rescinded at once. Since Brauchitsch was absent, Gersdorff met instead with General Eugen Müller, who informed him that the high command did not disagree with the army group. In fact Brauchitsch had already attempted on numerous occasions to have the orders canceled or at least amended. But each time, Hitler burst into a rage; during Brauchitsch’s last visit, he had even “hurled an inkwell” at him. “He won’t go see the Führer anymore,” Müller concluded laconically. Returning to the army group that evening, Gersdorff found Bock dining with his chief of general staff, Hans von Greiffenberg, and Tresckow, Hardenberg, and Lehndorff. When Gersdorff reported the failure of his mission a deep hush descended. Then Bock, who was the first to regain his composure, remarked “almost triumphally”: “Let it be noted, gentlemen, that Field Marshal Bock protested.” 10

Gersdorff later pointed out that if the commanders in chief of the army groups had jointly refused to obey Hitler, as Tresckow suggested, the Führer would have been forced to yield. It would have been impossible to replace such key commanders just ten days before the start of the campaign. We also know through Gersdorff that all the senior officers, at least in Army Group Center, objected to the orders and did what they could to prevent their being carried out. Tresckow made some attempts to influence the other two army groups in this direction. Considerable controversy persists, however, as to the extent to which these and other such efforts were successful.

Tresckow realized, of course, that opposition from army commanders could do little to prevent the Einsatzgruppen from carrying out mass murders behind the front. Army Group Center could, however, bring some influence to bear. Arthur Nebe, the leader of Einsatzgruppe B in its area, had moved in opposition circles since 1938 and had only accepted his assignment after great emotional conflict and largely at the urging of Oster and Gisevius, who hoped that he would be able to supply the opposition with information from the innermost sanctums of power in the SS. Nebe hinted to Tresckow that he intended to report his missions completed when in fact they were not. Ultimately, Field Marshal Bock came to an agreement with Field Marshals Kluge and Weichs and General Guderian that it was “undesirable” for the orders to be carried out. In the spring of 1942, almost one year later, the Commissar Order was officially rescinded. 11

Still, the army had hardly covered itself with glory. For the first time Hitler had tried to make it an accomplice in his crimes without receiving a clear refusal. Since the Röhm affair, the army had been careful not to allow itself to be drawn directly into criminal activities; at most, it exposed itself to accusations of standing aside and failing to help the victims. Now Hitler had succeeded on his first attempt in eliminating the distinction-still maintained in Poland up to this point-between military men engaged in traditional warfare and the murderousEinsatzgruppen. The one became caught up with the other in a war of annihilation that criminalized everyone who took up arms in the name of the German Reich. There could be no more talk of the sort that was common in the apologia written by former members of the Wehrmacht after the war, of having been “swept away” by events against one’s will and without sufficient knowledge. Hitler had without a doubt been encouraged to believe that he could get away with this final step by the supine resignation demonstrated by the generals over the years, their occasional outbursts of indignation not-withstanding.

This failure meant that the last opportunity of demonstrating to Hitler the limits to his power had been squandered. Brauchitsch would later claim that he sabotaged Hitler’s criminal orders by issuing special instructions stressing that a soldier’s primary duty was to fight and move on, not to engage in search-and-destroy operations. This strategy, however, amounted merely to a repetition of the failed tactic that the army had already practiced in Poland of abandoning conquered territories to the violence of the Einsatzgruppen and conspicuously washing its hands of any responsibility for what would follow.

It is true, of course, that opposition would have had little more than a delaying effect. This is no excuse, however, for either Brauchitsch or the other commanders. They failed to see that the restoration of the long-lost moral integrity of the army was at stake. Their failure to act seems even more egregious in the light of the unanimous sense of outrage expressed by the officers, of which so much was made following the war. It illustrates not only the widespread awareness of criminal activity but also the broad support that a determined commander who refused to carry out orders would have enjoyed. It is difficult to comprehend why three or more commanding generals could not agree to protest the orders as a body. It has repeatedly been argued that such a gesture would have been pointless, but it must be said that it was never really tried. Rundstedt’s aide, Hans Viktor von Salviati, remarked shortly before the Russian campaign began that almost all the field marshals were well aware of what was happening, “but that’s as far as it goes.” 12

* * *

At 3:15 a.m. on June 22, 1941, Hitler launched the war against the Soviet Union under the code name Operation Barbarossa. He had enjoyed an unbroken string of victories, including the last-minute campaigns against Greece, Albania, and Yugoslavia and the brilliant expedition in North Africa, where Rommel had succeeded in less than twelve days in reconquering all of the Libyan territory lost by Germany’s Italian allies. Although these victories had fueled a widespread feeling of invincibility, a nagging sense of foreboding began to arise for the first time. “When Barbarossa starts, the world will hold its breath and keep still,” Hitler crowed just a few days before the invasion.

Most of all, though, it was the Germans who held their breath. Everyone sensed that the mission that had been embarked on was too ambitious even for Hitler’s formidable nerves of steel, his keen intuition, and his eerie ability to stride from one triumph to the next. For the first time, the feeling arose that he was setting out to achieve the impossible. “Our German army is only a breath of wind on the endless Russian steppes,” said a staff officer who knew the terrain well. Almost all contemporary reports of the mood of the German people speak of “dismay,” “agitation,” “paralysis,” and “shock.” Occasionally, as one of the secret agents noted, there were “references to the fate of Napoleon, who was vanquished in the end by the vast Russian spaces.” 13

As the German armies advanced, so did the Einsatzgruppen. They set about their work with such brutality that Colonel Helmuth Stieff wrote in a letter that “Poland was nothing by comparison.” He felt as if he had become the “tool of a despotic will to destroy without regard for humanity and simple decency.” A general staff officer with Army Group North reported that in Kovno, Lithuanian SS squads had “herded a large number of Jews together, beaten them to death with truncheons, and then danced to music on the dead bodies. After the victims were carted away, new Jews were brought, and the game was repeated!” 14Officers in this army group besieged their superiors with demands that the massacres be halted. Similarly, the members of Army Group Center’s general staff, who had by this lime been transferred to Smolensk, urged Field Marshal Bock “with tears in their eyes” to put a stop to the “orgy of executions” being carried out by an SS commando unit about 125 miles away in Borisov and witnessed by Heinrich von Lehndorff from an airplane. Attempts were immediately made to stop the massacre, but they came too late. Bock demanded that the civilian commissioner in charge, Wilhelm Kube, report to him immediately and turn over the responsible SS commander for court-martial. Kube responded curtly that Bock ought rightly to be reporting to him and that he had no intention, in any case, of producing the SS commander. The army group could not even determine his name; the commandant of army headquarters at Borisov, whom the army group accused of failing to prevent the slaughter, committed suicide. 15

Читать дальше

![Traudl Junge - Hitler's Last Secretary - A Firsthand Account of Life with Hitler [aka Until the Final Hour]](/books/416681/traudl-junge-hitler-s-last-secretary-a-firsthand-thumb.webp)