When Hitler finished speaking there was a moment of stunned silence. But he had scarcely left the room before the marshals besieged Commander in Chief Brauchitsch, talking and gesticulating wildly. No one had any doubt, it seems, about the real meaning of Hitler’s words. Brauchitsch stood firm against the waves of complaints and references to international law, saying he had already done all he could but Hitler was not to be dissuaded. According to a Statement that Jodl made at the Nuremberg trials, Brauchitsch and Hitler did indeed have a number of “very heated conversations.” Halder tried to persuade Brauchitsch that the two of them should resign together, but the commander in chief was incapable of making a decision of that magnitude. 4

Hitler knew better than to rely solely on appeals for harshness. A number of preparatory guidelines were soon issued transferring the Wehrmacht’s responsibility for the administration of the occupied territories to special Reich commissioners. Heinrich Himmler and four Einsatzgruppen were commissioned to undertake “special tasks” arising “from the final battle of two opposed political systems.” The dry administrative language outlining directives for the planned “war of ideologies” could hardly disguise the extent to which the basic principles of international law and warfare were being thwarted. Two of the most infamous directives were the decree on military law and the so-called Commissar Order. The former transferred responsibility for punishing crimes against enemy civilians from military courts to individual division commanders, while the latter required that Red Army political commissars be segregated upon capture and, “as a rule, immediately shot for instituting barbaric Asian methods of warfare.” When Oster produced the documents at a meeting in Beck’s house, “everyone’s hair stood on end,” according to one who was there, “at these orders for the troops in Russia, signed by Halder, that would systematically transform military justice for the civilian population into a caricature that mocked every concept of law.” They all agreed that, “by complying with Hitler’s orders, Brauchitsch is sacrificing the honor of the German army.” 5In the first half of June, two weeks before the invasion was launched, the “Commissar Order” was issued to the staffs at the front as the last of a series of preparatory edicts.

* * *

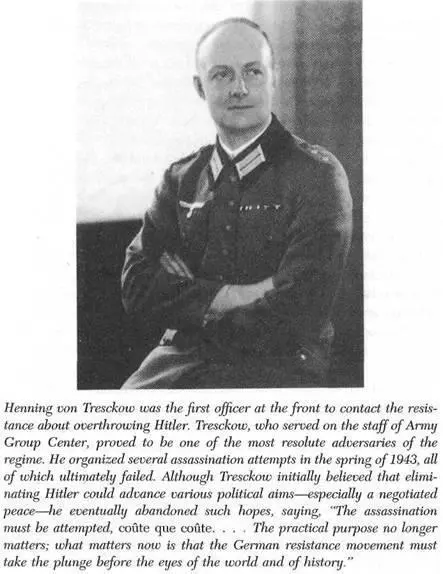

Henning von Tresckow was the first general staff officer of Army Group Center, headquartered in Posen at the time. Those who were close to him all recalled the strong impression he made, his “leadership qualities,” “distinguished manner,” “sense of honor,” and “Prussianness.” These descriptions do more, however, to obscure his character than to illuminate it.

Next to Stauffenberg, he was the most remarkable figure in the military resistance, displaying not only the mental discipline and passionate moral sense of the other conspirators but also great coolness under pressure, decisiveness, and daring. The so-called Kaltenbrunner reports of the interrogations carried out after the July 20 assassination attempt describe him as the “prime mover” and the “evil spirt” behind the plot. 6Originally an admirer of National Socialism, Tresckow did not have to wait for Hitler’s blatant warmongering to see the error of his ways. The continual illegal acts, the persecution of minorities, the suppression of free speech, and the harassment of churches had long since turned him against the party. Unlike many others, he realized early on that the “excesses” of the Nazi regime were not excesses at all but its real nature. And with the same frankness with which he had once supported Hitler, he now began to criticize him. When one of his army comrades defended the regime, Tresckow vehemently disagreed and ended by predicting that a dispute like this could easily lead to their taking up arms on opposite sides some day. Indeed, the commander of the First Regiment of Foot Soldiers had once prophesied that young officer Tresckow would end up as either chief of general staff or a mutineer mounting the scaffold. 7

At the time of the dispute over the western offensive, Tresckow attempted “in total despair” to organize a revolt. He urged his uncle Fedor von Bock, commander in chief of Army Group B, as well as Rundstedt and his chief of staff Erich von Manstein, to take action. But the generals “did not want to hear about any schemes directed against Hitler.” They were merely experts in military strategy, they replied, closing their minds to further persuasion. For the first time, Tresckow felt “contempt for the army leaders,” according to his biographer, Bodo Scheurig, and steeled himself to take matters into his own hands. But ironically, it was probably he who ensured that Brauchitsch and Halder did not scuttle Manstein’s “scythe-cut” strategy for penetrating deep into France with tanks and other armored vehicles, which later proved so successful. Tresckow’s former regimental comrade Rudolf Schmundt was now serving as Wehrmacht adjutant at Hitler’s headquarters, and Tresckow succeeded in persuading him to present Manstein’s plan to Hitler, who immediately saw its daring ingenuity and revised the invasion strategy. 8

Tresckow’s own plans for a coup began to take shape after he was assigned to Posen and the preparations for war against the Soviet Union had begun in earnest. He systematically placed officers who shared his views on the army group general staff, eventually filling all the key positions. First, to the astonishment and probably also the chagrin of his colleagues, he hired the strictly “civilian-minded” lawyer and reserve lieutenant Fabian von Schlabrendorff. Tresckow valued Schlabrendorff’s prudence and judgment and made him his closest adviser. Tresckow also had General Staff Major Rudolph-Christoph von Gersdorff transferred from an infantry division. Gersdorff was a cavalry officer who, as Tresckow had discovered in the course of a chance encounter, agreed with him about the contemptible nature of the Nazi regime. Gersdorff combined rectitude with great presence of mind and courage, as well as a charmingly adroit manner. Tresckow also attracted two other majors, Count Carl-Hans Hardenberg and Berndt von Kleist, and Count Heinrich Lehndorff, a lieutenant, all of old Prussian stock. Eventually they were joined by Lieutenant Colonels Georg Schulze-Büttger and Alexander von Voss, First Lieutenant Eberhard von Breitenbuch, Georg and Philipp von Boeselager, and a number of others. It was later observed quite correctly that the largest and most tightly knit resistance group of those years could be found right on the general staff of Army Group Center.

When the edict on the application of military law and the Commissar Order arrived at Army Group Center, Tresckow immediately had the commander in chiefs plane prepared for takeoff and went, with Gersdorff, to see Bock. On a pathway through a small park leading to Bock’s villa, Tresckow suddenly stopped. “If we don’t convince the field marshal to fly to Hitler at once and have these orders canceled, the German people will be burdened with a guilt the world will not forget in a hundred years. This guilt will fall not only on Hitler, Himmler, Göring, and their comrades but on you and me, your wife and mine, your children and mine,” he said to Gersdorff. “Think about it.” 9

Bock, who had attended the officers’ meeting on March 30, 1941, must therefore have been expecting these orders, but he expressed outrage upon receiving them, repeatedly exclaiming “Unbelievable!” and “Horrible!” during Gersdorff s summary of their contents. Nevertheless, he turned a cold shoulder to the suggestion that he immediately fly to Führer headquarters with Gerd von Rundstedt and Wilhelm von Leeb, the commanders in chief of Army Groups South and North, and disavow obedience to Hitler. The Führer, Bock said, would simply “throw him out” and possibly install Himmler in his place.Tresckow answered coldly that he could handle that.

Читать дальше

![Traudl Junge - Hitler's Last Secretary - A Firsthand Account of Life with Hitler [aka Until the Final Hour]](/books/416681/traudl-junge-hitler-s-last-secretary-a-firsthand-thumb.webp)