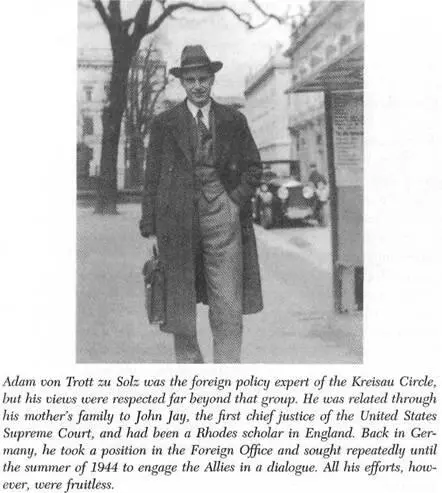

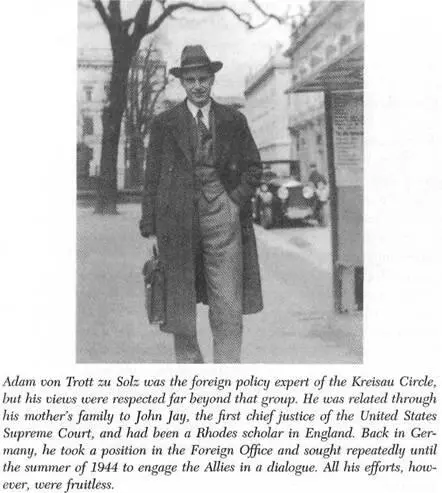

This was the crux of the matter, the issue that many believed would make or break the resistance. If the leverage Germany still had, however weak it might be, could not be used to negotiate a peace treaty, then the resistance might as well avoid the extremely dangerous, if not suicidal, risk of a coup attempt and simply watch the regime go down in flames. The opposition’s foreign policy experts-primarily Ulrich von Hassell but also Adam von Trott and others-decided after much deliberation that in view of all the Nazis’ broken promises, violence, and crimes, there was no certainty that an “acceptable peace” could be negotiated, but that at the very least it remained a possibility. 5

Such a hope was inconceivable unless the Allies were prepared to distinguish between Hitler and the German people. The conspirators based the plans for their own uprising entirely on the belief that this distinction existed and on the need to emphasize it for the benefit of everyone, so as to expose the falsity of the Nazi propaganda campaigns that depicted the Führer and the Volk as one. It is true that that hope for a negotiated peace revived many of the opposition’s shattered illusions and unrealistic aspirations, but despite the criticism that has in hindsight been levied against it, the resistance did have a legitimate basis for the way it proceeded. Neither the keenness nor the morality of its opposition to the regime is diminished by the fact that it continued to take the national interest into account. One could even say that those who combined their moral outrage at Hitler with an awareness of the political disaster he was heaping on Germany understood more thoroughly than anyone else the nature of the regime and the possibilities of taking action against it.

From a practical point of view, this meant they needed to be clear about the prospects facing a German government once the Nazis had been overthrown. Realizing that many concessions and guarantees would inevitably be extracted from Germany, the members of the resistance wanted to find out what the Allies’ maximum demands might be and to ensure that they themselves would be recognized, in theory at least, as equal partners in a European peace plan. What they did not want was to become the managers of a “liquidation commission” that simply carried out the dictates of the Allied powers. The opposition fully realized that such a situation would leave it standing “right in the middle of all the filth,” in the dramatic words of one member. 6

The resistance continued to pin its hopes on London, despite the misunderstandings, exasperation, and devastating setbacks that had characterized its overtures in the late 1930s. In focusing on this relationship, the German resistance considerably overestimated Britain’s role and influence in the Allied coalition; for quite some time London had not had the power to sign agreements of its own with anyone. Most of the conspirators felt, however, that Britain was somehow closer to them-and not just geographically. In comparison with the other two great powers, the United States and the Soviet Union, Britain seemed to stand for a less foreign, more European world. Just as opposition emissaries had traveled to the British capital in the late thirties, they now sought to pave the way for talks with London through British posts in neutral countries.

Theo Kordt had already attempted to do so at the outset of the war, having been dispatched by the Foreign Office to Bern, Switzerland, for precisely that purpose. All his efforts came to naught, however, as did those of Josef Wirth, the former German chancellor, who had emigrated to Switzerland; Carl Jacob Burckhardt; Willem Adolf Visser’t Hooft, the secretary-general of the provisional World Council of Churches in Geneva; and many others. In May 1941 Goerdeler passed along to the British government a peace plan approved by Brauchitsch; the cabinet declined even to acknowledge it. The British middleman informed his German contact that he had been forbidden to accept any such documents in the future.

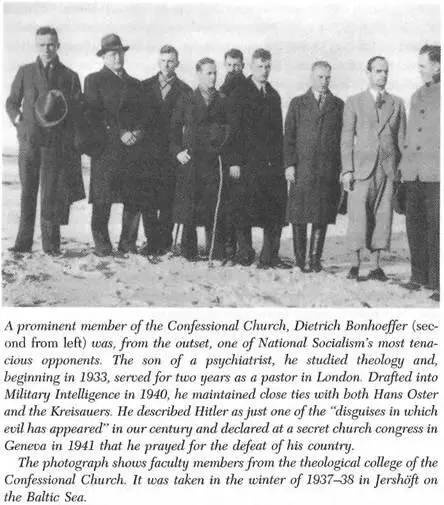

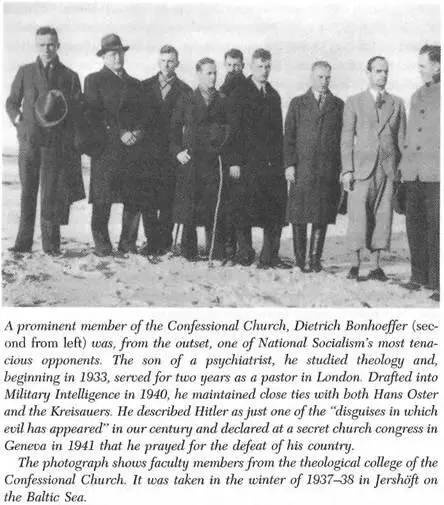

Another series of attempts to establish contact had been under way in Stockholm since the early 1940s and revolved largely around Theodor Steltzer, a key member of the Kreisau Circle. In May 1942 Bishop George Bell of Chichester met with Dietrich Bonhoeffer and his fellow clergyman Hans Schönfeld in Stockholm. Without knowing anything about the plans of the other, the two Germans had both decided to go to Sweden when they learned that Bell would be there. They told him about the opposition and the Kreisauers’ ideas for peace and expressed the hope that some token of encouragement might be offered. Bell was quite well acquainted with Bonhoeffer, who had been a pastor in the German church in London during the 1930s, and knew that he was one of the leading figures in the Confessional Church in Germany. A man of radical religious conviction, Bonhoeffer had repeatedly insisted that Hitler had to be “exterminated” regardless of the political consequences. At a secret church conference in Geneva in 1941 he had gone even further, announcing that he prayed for the defeat of his country because that was the only way Germany would be able to atone for the crimes it had committed. 7Schönfeld, on the other hand, brought only one question: Would the Allies adopt a different stance toward a Germany that had liberated itself from Hitler than they would toward a Germany still under his rule? Bell forwarded a report to the British Foreign Office, but Anthony Eden wrote back only to say he was “satisfied that it is not in the national interest to provide an answer of any kind.” When Bell approached the British Foreign Office again, Eden noted in the margin of his reply, “I see no reason whatsoever to encourage this pestilent priest!” 8

One year later Helmuth von Moltke went to Stockholm for a week, taking with him some information about the White Rose and one of its leaflets, as if he felt impelled to prove the seriousness of his opposition to the Nazi regime. Eugen Gerstenmaier, the theologian, and Hans Lukaschek, a lawyer who had joined the Kreisau Circle, also traveled to Stockholm, as on a number of occasions, did Adam von Trott, whose words sounded a desperate appeal for help: “We cannot afford to wait any longer,” he pleaded to a Swedish friend. “We are so weak that we will only achieve our goal if everything goes our way and we get outside help.” 9

But there was to be no help or any sign of encouragement, just a deep, persistent silence. The Allies did not even trouble themselves to reject the various attempts to contact them; they simply closed their eyes to the German resistance, acting as if it did not exist. Men like Bonhoeffer, Trott, Gerstenmaier, and Steltzer felt united with the Allies in their abhorrence for their common “archenemy” and their realization of the danger that he posed. They therefore imagined themselves closely affiliated with the Allied struggle against this monstrous tyranny, which, in Churchill’s words, had never been surpassed in the “dark, lamentable catalog of human crime.” This was an illusion for which the conspirators would pay with countless humiliations. Perhaps they were ahead of the times in their moral internationalism, which had met with such deep incomprehension in the conversations of 1938-39. At any rate, the sense of common ground on which they based their appeals was not shared by the British, who could never free themselves of the suspicion that they were dealing with a bunch of traitors, or Nazis in disguise. The phenomenon of committing “treason” for high moral or philosophical purpose, which has become so characteristic of the twentieth century, was an enigma to them.

Читать дальше

![Traudl Junge - Hitler's Last Secretary - A Firsthand Account of Life with Hitler [aka Until the Final Hour]](/books/416681/traudl-junge-hitler-s-last-secretary-a-firsthand-thumb.webp)