Since the equivalence principle is essentially the condition that the law of inertia holds in small regions of space-time, and all clocks rely in one way or another on inertia, this is the ultimate explanation of why it is relatively easy (nowadays at least) to build clocks that all march in step. They all tick to the ephemeris time created by the universe through the best matching that fits it together.

A SUMMARY AND THE DILEMMA

We have reached a crucial stage, and a summary is called for. In all three forms of classical physics – in Newtonian theory, and in the special and general theories of relativity – the most basic concept is a framework of space and time. The objects in the world stand lower in the hierarchy of being than the framework in which they move. We have been exploring Leibniz’s idea that only things exist and that the supposed framework of space and time is a derived concept, a construction from the things.

If it is to succeed, the only possible candidates for the fundamental ‘things’ from which the framework is to be constructed are configurations of the universe: Nows or ‘instants of time’. They can exist in their own right: we do not have to presuppose a framework in which they are embedded. In this view, the true arena of the world is timeless and frameless – it is the collection of all possible Nows. Dynamics has been interpreted as a rule that creates histories, four-dimensional structures built up from the three-dimensional Nows. The acid test for the timeless alternative is the number of Nows needed in the exercise. If two suffice, perfect Laplacian determinism holds sway in the classical world. It will have a fully rational basis. There will be a reason for everything, found by examination and comparison of any two neighbouring Nows that are realized. There is perfection in such dynamics: every last piece of structure in either Now plays its part and contributes, but nothing more is needed.

In non-relativistic dynamics, Newton’s seemingly incontrovertible evidence for a primordial framework and the secondary status of things can be explained if the universe is Machian. Then the roles will be reversed, things will come first, and the local framework defined by inertial motion will be explained. However, without access to the complete universe such a theory cannot be properly tested. In any case, the Newtonian picture is now obsolete even if it did clarify the issues. In general relativity the situation is much more favourable and impressive, since the best matching is infinitely refined and its effects permeate the entire universe. We can test for them locally. Finding that they are satisfied at some point in space-time is like finding a visiting card: ‘Ernst Mach was here’. The strong evidence that Einstein’s equations do hold suggests that physics is indeed timeless and frameless.

For all that, the manner in which space-time holds together as a four-dimensional construct is most striking. It is highlighted by the fact that there is no sense in which the Nows follow one another in a unique sequence. This is what, in the Newtonian case, gives rise to the beautifully simple image of history as a curve in Platonia. But in special relativity and, much more strikingly, in general relativity such a unique curve of history is lost. One and the same space-time can be represented by many different curves in Platonia. Even though no extra structure beyond what already exists in Platonia is needed to construct space-time, the way it holds together convinces most physicists that space-time (with the matter it contains) is the only thing that should be regarded as truly existing. They are very loath to accord fundamental status to 3-spaces in the way the dynamical approaches of Dirac, ADM and BSW require. Even though most of them grant that quantum theory will almost certainly modify drastically the notion of space-time, they are still very anxious to maintain the spirit of Minkowski’s great 1908 lecture. They are convinced that space and time hang together, and they want to preserve that unity at all costs. Within the purely classical theory, it seems to me that the argument is finely balanced. Perhaps an unconventional image of space-time will show how delicate this issue – space-time as against dynamics – is.

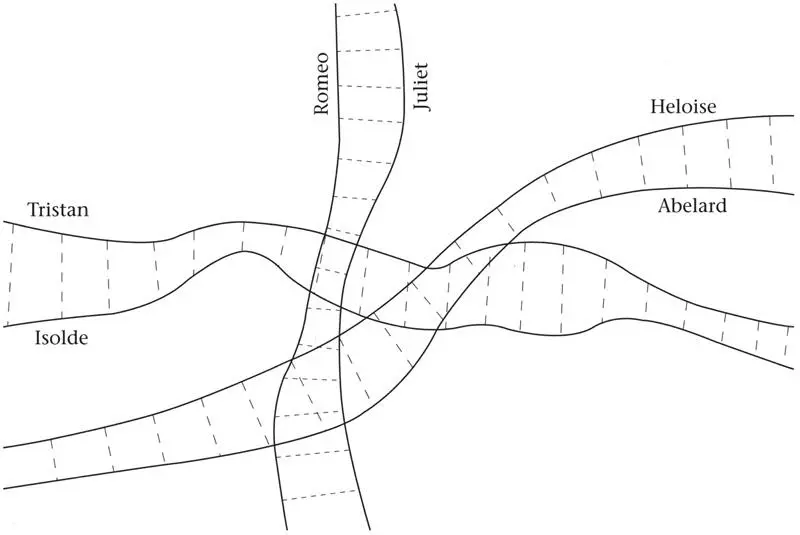

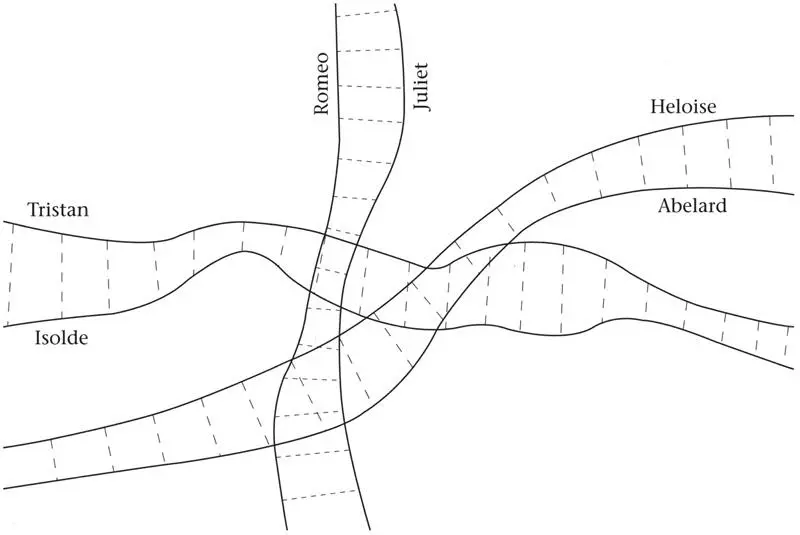

Wagner’s opera Tristan und Isolde is widely regarded as a highpoint of the Romantic movement in music. General relativity is the ne plus ultra of dynamics. More explicitly, the way in which two 3-spaces are fitted together in its dynamical core is like two lovers seeking the closest possible embrace. This is the level of refinement at work in the principles that create the fabric of space-time. It is vastly more than just a four-dimensional block. Everywhere we look, it tells the same great story but in countless variations, all interwoven in a higher-dimensional tapestry. This is what Einstein made out of Minkowski’s magical pack of cards. Look at space-time one way, and we see Tristan and Isolde hanging, Chagall-like, in the sky. Look another way, and we see Romeo and Juliet, yet another way and it is Heloise and Abelard. All these pairs, each perfect in themselves, are all made out of each other. They and their stories stream through each other. They create a criss-cross fabric of space-time (Figure 31).

Figure 31.Space-time as a tapestry of interwoven lovers. Given just the ‘intrinsic structure’ of Tristan and Isolde, the BSW formalism determines in principle all the points on Tristan that will be paired with points on Isolde. The lengths of the struts (proper time between matched points) are obtained as a by-product of the basic problem – finding the ‘best position’ for the closest possible embrace. They are therefore shown as dashes. The lengths of the struts are local analogues of ephemeris time and, as they separate Tristan and Isolde, are simply the most transparent way of depicting the intrinsic difference between the two of them. The struts between the other pairs of lovers are determined similarly. We can see how the difference that keeps Tristan apart from Isolde is actually part of the body of Romeo (and Juliet). The struts between Romeo and Juliet are drawn with short dashes because they have a space-like separation. Einstein’s equations and the best-matching principle hold, however space-time is sliced.

It stretches to the limit the notion of substance. For the body of space-time, its fattening in time, is just the way we choose to hold things apart so that the story unfolds simply. At least, it is in Newtonian space-time. All the dynamics – what actually happens – is in the horizontal placing. We pull the cards apart in a vertical direction that we call time as a device for achieving simplicity of representation. Time is the distinguished simplifier. The substance is in the cards. They are the things; the rest is in our mind.

General relativity adds an amazing twist to this seemingly definitive theory of time. Considered alone, Tristan and Isolde are substance, and the separation between them is just the measure of their difference. They cannot come together completely simply because they are different. This difference we call time. But what is representation of difference between Wagner’s lovers is part of the very substance of Shakespeare’s lovers. Romeo and Juliet would not be what they are if Tristan and Isolde were not held apart by their difference. The time that holds Tristan apart from Isolde is the body of Romeo. This interstreaming of essence and difference all in one space-time is even more remarkable than Minkowski’s diagram containing two rods each shorter than the other.

Читать дальше