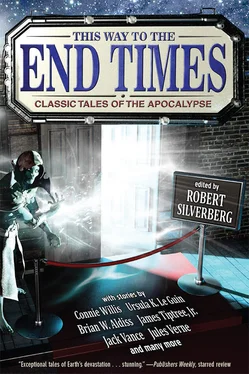

This Way to The End Times

CLASSIC TALES OF THE APOCALYPSE

EDITED BY Robert Silverberg

High Praise for This Way to The End Times

A PESSIMIST’S DREAM comes true in 21 exceptional tales of Earth’s devastation and humans’ inventive, and often ironically self-destructive, ways of surviving. Themes of religion, flooding, Adam and Eve, Atlantis, aliens, misogyny, and government oppression permeate the collection, which contains works written between 1906 and 2016 by science fiction legends as well as new authors. . . . These stunning stories contemplate survival while questioning whether life is worth saving, and many have such rich ideas and settings that they could easily spark full-length novels.

—PUBLISHERS WEEKLY,

Starred Review

APOCALYPTIC FICTION IS still a very hot trend, but as award-winning sf writer and editor of this collection Silverberg notes in the introduction, it’s hardly a new one: “Humankind seems to take a certain grisly delight in stories about the end of the world, and the market in apocalyptic prophecy has been bullish for thousands, or, more likely, millions of years. . . .” With its range of contributors, this is a much needed volume that will both satisfy the high demand for apocalyptic tales and remind readers of the actual breadth and depth of this literature of the end of the world.

—ALA BOOKLIST,

Starred Review

THE STORIES ARE uniformly good and frequently excellent. . . . The variety of ways in which these stories choose to end the world offers a great deal—nightmarish, funny, lonely, or hopeful—for the imagination. Wonderfully written, surprisingly varied apocalyptic tales.

—KIRKUS REVIEWS

SCIENCE FICTION LEGEND Robert Silverberg has picked the best of the very best stories for this volume. Absolute gold, from first word to last gasp!

—JONATHAN MABERRY,

New York Times bestselling author of

Mars One and

Kill Switch

And God saw that the wickedness of man was great in the earth, and that every imagination of the thoughts of his heart was only evil continually.

And it repented the Lord that he had made man on the earth, and it grieved him at his heart.

And the Lord said, I will destroy man whom I have created from the face of the earth; both man and beast, and the creeping thing, and the fowls of the air; for it repenteth me that I have made them.

— GENESIS 6: 5–7

Introduction

BY ROBERT SILVERBERG

THIS BOOK’S EPIGRAPH COMES FROM the one of the earliest pages of the Bible. We are told of the creation of the world in the first chapter of Genesis and by chapter six, after God has brought forth Adam and Eve and their progeny has multiplied greatly, the Lord has tired of His handiwork and, as quoted at the beginning of this book, resolves to cleanse the planet of it by sending a terrible deluge upon our ancestors.

Fortunately for us, He is not bent on total destruction: Noah is instructed to build an ark and bring his family aboard, and it is duly stocked with a host of creatures, “clean beasts and . . . beasts that are not clean . . . fowls . . . every thing that creepeth upon the earth.” Two by two they go aboard, dogs and cats and sheep and, I suppose, elephants and wombats and aardvarks as well, so that when the waters of the flood recede the world can begin anew, and here we are in what we Westerners call the twenty-first century, looking forward to the next terminal convulsion of our Maker’s mood.

The second volume of the Good Book lets us know that another apocalypse will eventually be heading our way. In the Second Epistle of Peter, chapter three, verse ten, we are advised that “the day of the Lord will come as a thief in the night; in the which, the heavens shall pass away with a great noise, and the elements shall melt with fervent heat, the earth also and the works that are therein shall be burned up.” And a few lines later, St. Peter tells us that inasmuch as all things thus shall be destroyed, it behooves us “to be in all holy conversation and godliness, looking for and hasting unto the coming of the day of God, wherein the heavens being on fire shall be dissolved, and the elements shall melt with fervent heat.” We should, we are told, “look for new heavens and a new earth, wherein dwelleth righteousness.” Once again we are given hope of ultimate redemption, although apparently it will be provided us in some other universe.

The apocalyptic warnings of the Bible, which culminate most spectacularly in the technicolor wonders of the Revelation of St. John the Divine (“And there appeared another wonder in heaven; and behold a great red dragon, having seven heads and ten horns, and seven crowns upon his heads. . . .”), were already ancient when the Scriptures, both New and Old, were set down a couple of thousand years ago. For whatever reason, humankind seems to take a certain grisly delight in stories about the end of the world, and the market in apocalyptic prophecy has been a bullish one for thousands or, more likely, millions of years. Even the most primitive of protohuman creatures, back there in the Africa of Ardipithecus and her descendants, must have come eventually to the realization that each of us must die; and from there to the concept that the world itself must perish in the fullness of time was probably not an enormous intellectual leap for those hairy bipedal creatures of long ago. Around their prehistoric campfires our remote hominid ancestors surely would have told each other tales of how the great fire in the sky would become even greater one day and consume the universe, or, once our less distant forebears had moved along out of the African plains to chillier Europe, how the glaciers of the north would someday move implacably down to crush them all. Even an eclipse of the sun was likely to stir brief apocalyptic excitement.

I suppose there is a kind of strange comfort in such thoughts: “If I must die, how good that all of you must die also!” But the chief value of apocalyptic visions, I think, lies elsewhere than in that sort of we-will-all-go-together-when-we-go spitefulness, for as we examine the great apocalyptic myths we see that not only death but resurrection is usually involved in the story—a bit of eschatological comfort, of philosophical reassurance that existence, though finite and relatively brief for each individual, is not totally pointless. Yes, the tale would run, we have done evil things and the gods are angry and the world is going to perish, in a moment, in the twinkling of an eye, but then will come a reprieve, a second creation, a rebirth of life, a better world than the one that has just been purged.

What sort of end-of-the-world stories our primordial preliterate ancestors told is something we will never know, but the oldest such tale that has come down to us, which is found in the 4,500-year-old Sumerian epic of Gilgamesh, King of Uruk, is an account of a great deluge that drowns the whole Earth, save only one man, Ziusudra by name, who manages to save his family and set things going again. Very probably the deluge story had its origins in memories of some great flood that devastated Sumer and its Mesopotamian neighbors in prehistoric times, but that is only speculation. What is certain is that the theme can be found again in many later versions: the Babylonian story gives the intrepid survivor the name of Utnapishtim, the Hebrews called him Noah, to the ancient Greeks he was Deucalion, and in the Vedic texts of India he is Manu. The details differ, but the essence is always the same: the gods, displeased with the world, resolve to destroy it, but then relent and bring mankind forth for a second try.

Читать дальше