‘Oh, please mind what you’re doing!’ cried Alice, jumping up and down in an agony of terror. ‘Oh, there goes his delicious nose’; as an unusually large saucepan flew close by it, and very nearly carried it off.

‘If everybody minded their own business,’ the Duchess said in a hoarse growl, ‘the world would go round a deal faster than it does.’

‘Which would not be an advantage,’ said Alice, who felt very glad to get an opportunity of showing off a little of her knowledge. ‘Just think of what work it would make with the day and night! You see the earth takes twenty-four hours to turn round on its axis—’

‘Talking of axes,’ said the Duchess, ‘chop off her head!’

Alice glanced rather anxiously at the cook, to see if she meant to take the hint; but the cook was busily stirring the soup, and seemed not to be listening, so she went on again: ‘Twenty-four hours, I think ; or is it twelve? I—’

‘Oh, don’t bother me ,’ said the Duchess; ‘I never could abide figures!’ And with that she began nursing her child again, singing a sort of lullaby to it as she did so, and giving it a violent shake at the end of every line:

‘Speak roughly to your little boy,

And beat him when he sneezes:

He only does it to annoy,

Because he knows it teases.’

CHORUS.

(In which the cook and the baby joined):

‘Wow! wow! wow!’

While the Duchess sang the second verse of the song, she kept tossing the baby violently up and down, and the poor little thing howled so, that Alice could hardly hear the words:

‘I speak severely to my boy,

I beat him when he sneezes;

For he can thoroughly enjoy

The pepper when he pleases!’

CHORUS.

‘Wow! wow! wow!’

‘Here! you may nurse it a bit, if you like!’ the Duchess said to Alice, flinging the baby at her as she spoke. ‘I must go and get ready to play croquet with the Queen,’ and she hurried out of the room. The cook threw a frying-pan after her as she went out, but it just missed her.

Alice caught the baby with some difficulty, as it was a queer-shaped little creature, and held out its arms and legs in all directions, ‘just like a sweet little meat pie,’ thought Alice, licking her lips and smacking her mouth. The poor little thing was snorting like a steam-engine when she caught it, and kept doubling itself up and straightening itself out again, so that altogether, for the first minute or two, it was as much as she could do to hold it.

As soon as she had made out the proper way of nursing it, (which was to twist it up into a sort of knot, and then keep tight hold of its right ear and left foot, so as to prevent its undoing itself,) she carried it out into the open air. ‘ If I don’t take this child away with me,’ thought Alice, ‘they’re sure to kill it in a day or two: wouldn’t it be murder to leave it behind?’ She said the last words out loud, and the little thing grunted in reply (it had left off sneezing by this time). ‘Don’t grunt,’ said Alice; ‘that’s not at all a proper way of expressing yourself.’

Alice gazed down into the wee face, wondering if anyone would notice if she took a bite of his fat little cheek, just something to nibble. Surely he had plenty of cheek to go round; no one would be the wiser if she had something to fulfill this mind-numbing hunger inside her. But before she could decide which cheek to taste first, the baby grunted again, and Alice looked very anxiously into its face to see what was the matter with it. There could be no doubt that it had a very pale cast to it now, and its eyes were rolled to the back of its head; its pink tongue was now blue and cold: altogether Alice did not like the look of the thing at all. ‘But perhaps it was only holding its breath to keep from sobbing,’ she thought, and looked into its eyes again, to see if there were any tears.

No, there were no tears. ‘If you’re going to turn into a corpse, my dear,’ said Alice, seriously, ‘I’ll have nothing more to do with you. Mind now!’ The poor little thing groaned and squirmed in her arms and they went on for some while in silence.

Alice was just beginning to think to herself, ‘Now, what am I to do with this cold thing when I get it home?’ when it groaned again, so violently, that she looked down into its face in some alarm. This time there could be no mistake about it: it was neither more nor less than a dead baby, and she felt that it would be quite absurd for her to carry it further.

So she set the little creature down, and felt quite relieved to see it crawl away quietly into the wood. ‘If it had stayed alive for a bit longer,’ she said to herself, ‘it would have made a wonderful meal: but it makes rather a handsome corpse, I think.’ And she began thinking over other children she knew, who might do very well as dinners and lunches, and was just saying to herself, ‘if one only knew the right way to serve them—’ when she was a little startled by seeing the Cheshire Cat sitting on a bough of a tree a few yards off.

The Cat only grinned when it saw Alice. It looked good-natured, she thought: still it had very long claws and a great many teeth and its sleek body and midnight black, so she felt that it ought to be treated with respect.

‘Cheshire Puss,’ she began, rather timidly, as she did not at all know whether it would like the name: however, it only grinned a little wider. ‘Come, it’s pleased so far,’ thought Alice, and she went on. ‘Would you tell me, please, which way I ought to go from here?’

‘That depends a good deal on where you want to get to,’ said the Cat.

‘I don’t much care where—’ said Alice.

‘Then it doesn’t matter which way you go,’ said the Cat.

‘—so long as I get somewhere ,’ Alice added as an explanation.

‘Oh, you’re sure to do that,’ said the Cat, ‘if you only walk long enough.’

Alice felt that this could not be denied, so she tried another question. ‘What sort of people live about here?’

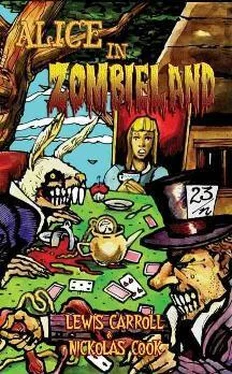

‘In that direction,’ the Cat said, waving its right paw round, ‘lives a Hatter: and in that direction,’ waving the other paw, ‘lives a Dead Hare. Visit either you like: they’re both zombies.’

‘But I don’t want to go among dead people,’ Alice remarked.

‘Oh, you can’t help that,’ said the Cat: ‘we’re all dead here. I’m dead. You’re dead.’

‘How do you know I’m dead?’ said Alice.

‘You must be,’ said the Cat, ‘or you wouldn’t have come here.’

Alice didn’t think that proved it at all; however, she went on ‘And how do you know that you’re dead?’

‘To begin with,’ said the Cat, ‘a living cat eats mice. You grant that?’

‘I suppose so,’ said Alice.

‘Well, then,’ the Cat went on, ‘you see, I like to eat little girls, not mice. Although a little girl and a mouse are quite the same in my eyes.’ And with that the Cheshire Cat’s eyes grew wider and wider until they were as large as two saucers full of milk and blood.

‘Little girls?’ said Alice. Suddenly her shivers were for an altogether different reason as the Cat’s teeth glistened under the sickly dim sunlight.

‘Yes, indeed. Little girls taste oh so delicious after a swift chase in the forest,’ said the Cat. ‘Do you play croquet with the Queen to-day?’

‘I should like it very much,’ said Alice, relieved that the conversation had turned away from eating young girls, ‘but I haven’t been invited yet.’

‘Surely an oversight, I’m certain,’ said the Cat. ‘Not to worry. The Red Queen always greets newcomers and visitors to Zombieland. She’s quite particular about making sure they know the rules.

Читать дальше