This is wat I had done at the weakend.

Miss Raine, Timothy’s teacher, finished reading the report and tapped her lower incisors with the butt of her pen. This made worrying reading; very worrying reading. Something really ought to be done. She took the exercise book, walked out of the marking room through the staffroom, and down the corridor to the headmaster’s study. She knocked and entered at his invitation.

“Good afternoon, Miss Raine,” he said as he finished pencilling in some numbers on the budget figures he was compiling. Miss Raine was notorious for making a big hoo-hah over nothing. He had no doubt that this was going to be more of the same. “And how can I help you?”

“It’s Timothy Chambers, Mr. Tanner. I’m a little concerned about his state of mind.”

“Tim Chambers? Really? He’s always struck me as perhaps a little overimaginative, but nothing that a few years of secondary school won’t knock out of him. What exactly is the problem?”

“He handed in a report today about what he did at the weekend.” She threw it on the desk. “It’s bordering on the psychotic.”

As Tanner leaned forward to pick up the report, he noticed that Miss Raine’s skirt stopped just shy of her knees. This was a new development. He frowned inwardly; there is such a thing as mutton dressing as lamb. On the other hand, they were unexpectedly appealing knees. Very appealing indeed. He flicked through the report but wasn’t really paying much attention. How was it that he’d never noticed what a handsome woman Miss Raine was? Very handsome, most attractive. Perhaps she had changed her hair? She was saying something about calling in the district school psychiatrist, and he nodded absently. A possible threat to the other children? Why, that would be most unpleasant. They must do everything in their power, in his power, to make sure that didn’t come to pass.

In the space of ten minutes, Timothy Chambers stopped being a nice, decent sort of lad, if a little prone to fancies, and had become a potential serial killer, arsonist, and cannibal. Psychiatric reports were a probability, observational internment a possibility, and removal from the school a certainty.

Tanner watched a pleased Miss Raine leave his study, and he wasn’t looking at her back. She turned at the door and added, “After all, I should know. I was at the carnival myself last night. I had a wonderful time.”

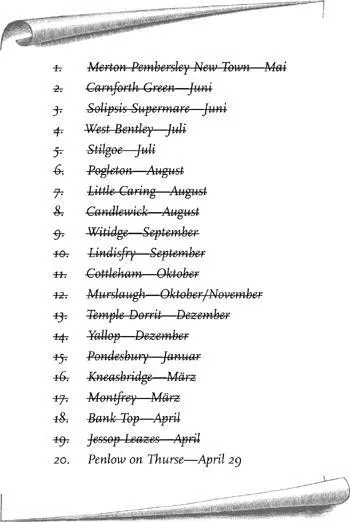

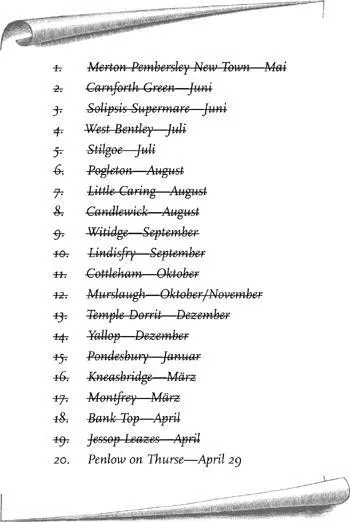

From the journal of the Reverend M***, vicar of Saint Keyna’s, Jessop Leazes. April 25th,

1 *** The rivalry of Mrs. J*** and Mrs. B*** has reached quite incendiary proportions. This week Mrs. B*** was charged with creating the floral arrangements for the church, a task she relishes. Indeed, she has always created quite most competent displays.

This morning, however, I was called to the church by the sexton, who told me, and I use his exact words, “The darrft ol’ biddy’s really done it this time, arr.” At the time I believed he meant that she had excelled herself in a positive sense. I discovered my mistake the instant that I entered the church.

The stench was appalling, breathtakingly so, like a poorly run pig farm. The source of the smell was immediately obvious. Where I would have expected to see examples of Mrs. B*** ’s work, there were instead the most extraordinarily repulsive piles of rotting vegetable matter.

I was in the process of discussing with the sexton how we should dispose of the mess, when Mrs. B*** herself entered. I could swear that there was an expression of pride upon her face, but it was wiped away so quickly by the smell, I cannot be sure. She was devastated. Yes, she admitted that she had supplied the floral arrangements as agreed, but could cast no light upon how it was that they had rotted in so short a time. She kept saying how beautiful they had been, how exotic.

I helped carry out the grotesquely wilted remains to the sexton’s wheelbarrow, which he had brought around for the purpose. An unenjoyable process: the flowers were wet and dripped some sort of ichor. The sexton was going to dump the mess on the composting heap in the corner of the churchyard, but I told him that I did not care to have such matter upon consecrated ground, to take it away entirely and burn it. This comment elicited a remarkable reaction from Mrs. B***. She put her hand to her mouth, and I heard her say, “Consecrated!” to herself, as if coming to a horrible realisation.

She was just hurrying off when Mrs. J*** arrived. She had her husband pushing along their own wheelbarrow, upon which were several floral pieces. Word travels quickly around the Green, but I was still astonished at the alacrity with which Mrs. J*** had leapt into the breach. Mr. J*** wheeled them through the gate, and again Mrs. B*** reacted unexpectedly, gasping as the barrow made its way through the churchyard.

There followed a harshly whispered conversation between the two women that seemed very unfriendly. From what little I could make out, it appears that they had both attended the funfair the previous evening. Mrs. B*** had purchased a quantity of exotic plants, the acquisition of which had required her to sell some personal item. These plants she had used in her arrangements, although why they had survived all the evening yet rotted so quickly when in the church defeated me. Mrs. J*** had also bought something there, presumably a book on flower arranging, for her work — though it uses only common, simple flowers — was the best I’ve ever seen.

Mrs. B*** left in a hurry, presumably after the fairground people to demand her money back, although they have already moved on in the night, and nobody seems to know where. I wish her well, but I fear this is most certainly a case of caveat emptor.

CHAPTER 10

in which the carnival reaches journey’s end and difficulties present themselves en masse

Francis Barrow folded the last bit of fried bread with his knife and fork, speared it, and used it to mop up the remains of the cooked yolk that had escaped from his poached egg. Placing his cutlery on the greasy plate, he picked up his tea and took an appreciative look out of his dining-room window It was a horribly unhealthy meal, of course, and one his daughter only allowed him to have once a fortnight. A luxury’s only a luxury if you don’t get it often, he thought, and picked up the local paper.

Leonie came in as he read the front page. “Anything exciting?” she asked as she cleared up the table.

He sniffed and flicked rapidly through the pages. “No, not really. They’re repainting the crossing in front of St. Cuthbert’s Primary, there’s a Beetle Drive at the parish hall on Friday, and we’re playing Millsby at the weekend, of course.”

His daughter laughed. “ ‘We’re playing Millsby’?” she said. “When was the last time you wore flannels?”

“Aye, well,” he said, and put the paper down. “Showing moral support, then.”

“It’ll be you and your cronies on the boundary, sitting there in deck-chairs with a relay of local lads running between you and the beer tent. You’re incorrigible.”

“It’s what cricket’s all about,” he said. He looked at her and could see his wife so strongly in the line of her chin and her nose. The tawny blond hair was all her own, but the way she set her face sometimes … Leonie had just turned twenty-five: the same age her mother had been when they’d married. All those years ago. His smile became sad.

There was a slightly frantic knock at the door. “I’ll get it,” said Leonie, and went out of the room and down the hall. Barrow could hear her speaking to Joe Carlton, who seemed busting to tell her something. After a moment, Joe himself came in, the most excited he’d been since he’d almost become mayor six years ago.

Читать дальше