Al-Jelidah was accustomed to this work, and scrambled about with phenomenal ease, clinging to minute protrusions of rock with fingers like steel bars. He went farther and faster than anyone else in the party. Suhail was not far behind him, though, using ropes where he could to assist his climb. “There are statues and inscriptions in some rather unlikely places,” he explained with a laugh, when I expressed my surprise. Tom, Andrew, and Haidar tramped about on the easier paths, searching every nook and cranny of the Labyrinth for possible clutches.

Which left me with the camels. Oh, I searched when I could—but my clothing hampered me, and even when I donned trousers, I lacked the strength and physical conditioning of my male companions, and could not get nearly so far. (Remembering this, I took the precaution of training before my next expedition, which came very much in handy.) I consoled myself by working on a map of the area, which Suhail said might be the first accurate attempt anyone had made since Mithonashri a hundred and fifty years before.

Our search took us deeper and deeper into the Labyrinth. One clutch we found had been raided by predators, like our original target; another had already hatched, which made me fret with impatience. Tom and I conferred and agreed that we should move onward, rather than studying the signs left behind at that one. What little we might learn was not worth the risk of missing the event itself elsewhere. If all else failed, we could always come back.

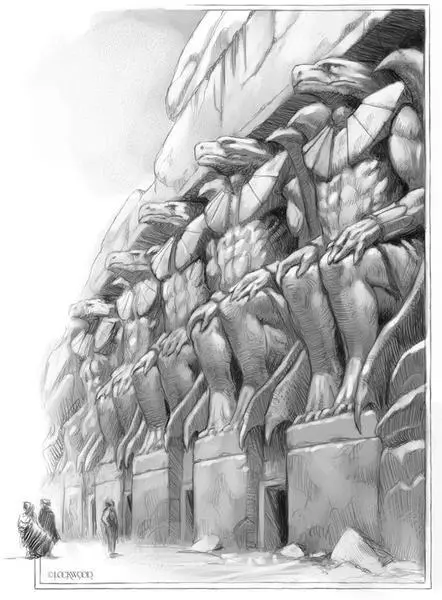

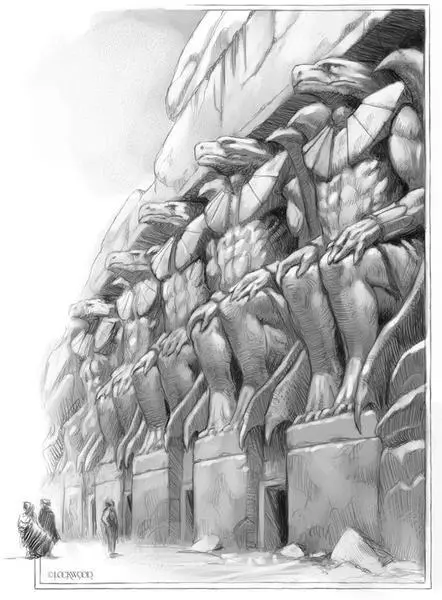

Suhail steered us a little, at the end. Not so far as to potentially miss a good spot—he would never have put our work at risk for a mere side trip—but when the choice came of going either left or right, he chose left, because he knew where it would lead. And so, on a morning in early Caloris, when the light was at its most dramatic angle, we emerged from a canyon barely wide enough for our camels to find ourselves facing the Watchers of Time.

* * *

If you have seen any images from the Labyrinth of Drakes, you have seen this site. The Watchers are five seated figures, fully twenty meters in height, carved into the sloping face of a canyon wall. They have the draconic heads and wings so typical of Draconean statuary, and seem to be gazing to the ends of eternity itself. Between them are four doorways, and above is an intricate frieze, depicting small flying dragons and human figures in chains.

The space that lies beyond those doorways has long been a mystery. All four open onto the same shallow antechamber, from which only a single archway gives access to the larger space within. This must have once contained furniture, paneling, or something else similarly flammable, for the walls of that chamber are covered with soot, which has almost completely obscured the murals that once decorated every square inch. Only bits and pieces can be made out, and efforts to clean away the soot have in many cases removed the murals as well. There is hope nowadays that our methods have improved, and the ancient artwork of that place might be seen at last… but so far, it has come to naught.

THE WATCHERS OF TIME

It was not what I had come to the Labyrinth to see, but even a woman as obsessed with living dragons as myself could not help marveling at the place. Had I grown up with such relics nearby, who is to say that I, too, would not have formed a fascination like Suhail’s? The Draconean ruins in Scirland are few and disappointing. The Watchers of Time took my breath away.

We camped nearby that night. Suhail admitted he had once laid his pallet within the antechamber itself—“But never again,” he said with feeling. “I hardly slept a wink that night. I was convinced the Watchers knew I was there, and did not approve.” I knew what he meant. Though I am not a superstitious woman, I did not want to sleep with their stony eyes on me; we went around a corner to a spot out of their sight.

We stood watches during the night while we were in the Labyrinth, for the groundwater allows vegetation to persist through the summer—which attracts various herbivores—which, in turn, attracts carnivores. Our tiny fires, built from camel dung, were not enough to keep them away. I alone was not expected to stand sentry, less on account of my sex, and more on account of having refused Andrew’s offer to teach me to shoot… but that night I slept very little regardless, thinking of the Draconeans and the world they had known.

The next morning my companions searched the area, while I stayed below and sketched the Watchers. (It was hardly necessary, as they have been a popular subject for every traveller who passes through the area and even some who have never even seen them—but I could not look upon those ancient guardians and not wish to render them with my own pencil.) We would not be able to stay long, and knew it. There had once been a well nearby, whose site Suhail pointed out, but it was so thoroughly collapsed that it would be less effort to dig a new one entirely. For water we would have to go some distance. One of our milk camels had foundered after the sandstorm, and the other was not giving as much as we had hoped.

From high above, I heard a triumphant shout.

I twisted on my seat to find Tom standing at the edge of the plateau across from the Watchers. He was a dusty blot against a sun-bleached sky, but he waved his hat to attract my gaze, and put his other hand to his mouth to direct his voice. “Up here!”

He had scraped his hands bloody getting up there—a fact I discovered after Suhail led me by an easier route. (I say “easier”; it is not the same thing as “easy.”) But his suffering paid off, for he had located a clutch of eggs, nestled in the cup of sand above.

From a dragon’s perspective, the site was ideal. The plateau was high enough that it received almost no shade, except in the very late morning and afternoon. It had a little dip in its center, though, which caught sand that would otherwise have blown away; and in this sand, the dragon had laid her eggs.

(I had the utterly fanciful thought that she had laid them: the first drake whose mating flight we observed, the one I lost track of when al-Jelidah prevented me from riding onward into the Labyrinth. The odds of it were small… but my mind does not always weigh odds rationally.)

From a naturalist’s perspective, the site left something to be desired. It was not close to water; furthermore, if Tom and I wished to observe the hatching, we would either have to sit in that cup with the newborn drakes—not a very wise idea—or else climb an even steeper hill a little way off and watch through field glasses.

This last, as you may imagine, is what we chose to do, while Andrew and al-Jelidah took our camels and went to acquire water.

There is nothing like an intellectual victory to distract one from miserable heat and thirst. We had found the clutch just in time: the very next day, when Tom and I were still trying to tent our cloaks over ourselves as shelter from the sun, the eggs began to hatch. I lay full-length on the burning stone for hours, field glasses glued to my face, putting them down only when necessary to sketch what I had seen. Suhail stepped around and over us with fabric and sticks, trying to make sure we would not die of heat exhaustion while we were too busy to notice. By the end of the day I had an excruciating headache, but I hardly cared—for I had, at last, seen desert drakes hatch.

Tom and I had both read Lord Tavenor’s accounts of the hatchings at Dar al-Tannaneen, of course. Many of those eggs produced unhealthy results, though, and we could not be certain how the change in their circumstances had altered the process. Watching that day, we treated the entire affair as a new observation, discarding all of our assumptions and noting every detail, no matter how small.

Читать дальше