He stopped me with one hand on my arm. So small a contact should not have meant so much—and yet it did. “For tonight,” he said, “we will find a place to stay in the city. I look forward to sharing your work with you, my love… but there are some parts of you I will not share with your work. And tonight is one of them.”

In which we discover a good deal more than anyone expected

Together in the House of Dragons—Ancient words—Testing to destruction—The desert in summer—Al-Sindi—Sandstorm—Broken shells

It is a common trope of romantic tales that the heroine declares she would gladly live in a garret if it meant being with her love. I was not prone to such dramatic utterances; but looking back on my actions, I suppose it would not have been far off the mark.

We resided at Dar al-Tannaneen for the remainder of my time in Qurrat, for Suhail remained unwelcome in his brother’s house. I shifted my belongings to a larger chamber (one which, coincidentally, was farther removed from the barracks in which the others slept), and we made plans for furnishing the room in a comfortable style—but it will surprise few of my readers, I think, if I say that we never followed through on those plans. Our arrangements there were haphazard, and remained so until I departed.

What need had I of furnishings? I had Suhail; I had Tom; I had dragons. Under no circumstances was I going to drag Jake with us into the desert—no matter how much he might have pleaded to go—but I wrote to him saying that he could miss the fall term at Suntley and come join us in Akhia instead. Even if my commission ended before then, I thought Jake deserved to reunite with his new stepfather and see where Suhail came from.

Much of the clutter in our new quarters belonged to Suhail, who relocated his entire library from his brother’s house to Dar al-Tannaneen. “I’ve had to keep half of this hidden under my bed,” he admitted, prying the lid off the first crate. “It will be nice to feel like an adult again.”

I borrowed his crow-bar and opened another crate. It is inevitable, I suppose, that one cannot unpack a box of books efficiently, at least not when the books belong to someone else; I was immediately diverted by looking through them. Of course I could not read three-quarters of their titles, as they were in Akhian or some other language I did not know—but that did not stop me from looking. And when I lifted a heavy green volume from the bottom, I found something I did recognize.

“Is this Ngaru?” I asked, pointing at the symbol on the front cover.

You may think it strange, but I had quite forgotten about the rubbing of the Cataract Stone I gave to Suhail. He and I had rarely been in the same place since then—and when we were, our minds were fully occupied with other troubles (such as Maazir and the Yelangese poisoner), or else we were busily pretending to be near-strangers to one another. It was not that the Cataract Stone had never crossed my thoughts again; rather that it never did so at a point when I could ask Suhail how he was getting on with it.

As it turned out, he had not gotten very far at all. He said, “That was one of the books I had to hide under my bed. Which is a very great pity, since I had to sell my soul to Abdul Aleem ibn Nahwan to get my hands on it—that’s a glossary and grammar of Ngaru.” A mischievous grin spread over his face, and he took the volume from me. “But I suppose, now that I am the idle husband of a prominent naturalist, I must occupy myself with something . And I have no idea how to do needlework.”

Even with his aptitude for languages, it was slow going. Suhail had never studied Ngaru before obtaining that book from his fellow scholar, and had devoted the months between then and now to the necessary first step of familiarizing himself with it. Translating the inscription was a painstaking process, and he warned me at every turn that he would need an expert to verify his text before he would be at all confident in the result. Indeed, he would not even share what he had with me until he worked his way through the entire piece. It is a very good thing that the House of Dragons kept me busy, or I would have hovered over his shoulder until he went out of his mind with distraction. Even though ancient civilizations and dead languages have never been my greatest love, I was champing at the bit to know what the stone said.

He unveiled the fruits of his labour one night over a private dinner. “The beginning of it is not the kind of thing to make anyone’s heart beat faster, except perhaps a scholar of early Erigan history. It is a list of names—a lineage, I think, for some early king. Then it goes on for some time about how that individual caused the stone to be set up in the ninth year of his reign—”

“Yes, yes,” I said impatiently. “Get to the interesting part.”

“Are you sure?” This time his grin was more diabolical than mischievous. “I could read that part to you, if you like, complete with footnotes about my uncertainty regarding case endings—”

“We are alone, Suhail. There is no one to see if I throw food at you.”

He laughed. Then, composing himself, he recited:

We are the patient, the faithful, those who continue when all others have abandoned the path. Obedient to the true masters, we make this stone in their name, in their hand as we remember it. Here the gods will be born anew: the jewels of the precious rain, the sacred utterances of our hearts, the transcendent ones, the messengers between earth and heaven. On their wings we will ascend once more to the heights. May the blood of the traitors be spilt on barren stones of their sin. Hear us, gods of our foremothers. We keep the faith, until the sun rises in the east and the Anevrai return.

Rapt though I was, that did not preclude my mind from seizing upon his words and picking them apart for meaning. “The sun rises in the east every morning. Either that is an error in your translation—which I doubt—or an error in their carving, or else some kind of ancient idiom. In which case we will likely never understand what they meant. ‘Gods of our foremothers’… I suppose they were matrilineal, as many Erigan peoples are today. But what does ‘Anevrai’ mean?” My breath caught. “Ngaru post-dates the fall of Draconean civilization, does it not? Is—is that what the Draconeans were called?”

“It might be.” Suhail was grinning from ear to ear. “Or it is the name of their gods. I cannot tell, from one text alone.”

And a brief text at that, if one discounted all the folderol about lineages and such. But there were hundreds, perhaps even thousands of texts out there. “Now that you can read the language, though—”

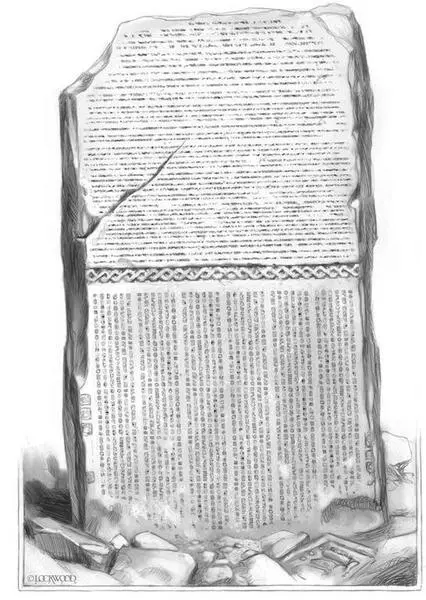

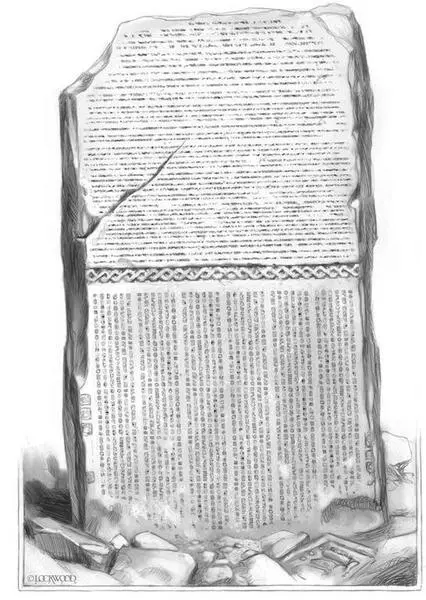

CATARACT STONE

He held up a cautioning hand, stopping my excitement before it flew away with me. “I cannot read Draconean. Not yet.”

I stared at him, confused. “But you know what it says.”

“Yes. My next challenge is to figure out how it says that. Which symbols say ‘gods’ in the Draconean tongue? Which ones say ‘faithful’? Are those single words in their tongue, or several? How do their verbs conjugate? What order do they phrase their sentences in? I gave it to you in Scirling, but in the Ngaru order you would say ‘stones barren’ instead of ‘barren stones.’ I cannot even be positive that the Draconean text reads the same—though ‘in their hand as we remember it’ suggests that it does.”

Читать дальше