Atvar glowered at the shiplord, though it was only natural that he try to put the best face on things. “Our facilities may not be badly damaged, but what of our prestige?” the fleetlord snapped. “Shall we give the Big Uglies the impression they can lob these things at us whenever it strikes their fancy?”

“Exalted Fleetlord, the situation is not so bad as that,” Kirel said.

“No, eh?” Atvar was not ready to be appeased. “How not?”

“They fired three more at our installations the next days and we knocked all of those down,” Kirel said.

“This is less wonderful than it might be,” Atvar said. “I presume we expended three antimissile missiles in the process?”

“Four, actually,” Kirel said. “One went wild and had to be destroyed in flight.”

“Which leaves us how many such missiles in our inventory?”

“Exalted Fleetlord, I would have to run a computer check to give you the precise number,” Kirel said.

Atvar had run that computer check. “The precise number, Shiplord, is 357. With them, we can reasonably expect to shoot down something over three hundred of the Big Uglies’ missiles. After that, we become as vulnerable to them as they are to us.”

“Not really,” Kirel protested. “The guidance systems on their missiles are laughable. They can strike militarily significant targets only by accident. The missiles themselves are-”

“Junk,” Atvar finished for him. “I know this.” He poked a claw into a computer control on his desk. The holographic image of a wrecked Tosevite missile sprang into being above the projector off to one side. “Junk,” he repeated. “Sheet-metal body, glass-wool insulation, no electronics worthy of the name-”

“It scarcely makes a pretense of being accurate,” Kirel said.

“I understand that,” Atvar said. “And to knock it out of the sky, we have to use weapons full of sophisticated electronics we cannot hope to replace on this world. Even at one for one, the exchange is scarcely fair.”

“We cannot show the Big Uglies how to manufacture integrated circuits,” Kirel said. “Their technology is too primitive to let them produce such sophisticated components for us. And even if it weren’t, I would hesitate to acquaint them with such an art, lest we find ourselves on the receiving end of it in a year’s time.”

“Always a question of considerable import on Tosev 3,” Atvar said. “I thank the forethoughtful spirits of Emperors past”-he cast his eyes down to the floor, as did Kirel-“that we stocked any antimissiles at all. We did not expect to have to deal with technologically advanced opponents.”

“The same applies to our ground armor and many other armaments,” Kirel agreed. “Without them, our difficulties would be greater still.”

“I understand this,” Atvar said. “What galls me still more is that, despite our air of superiority, we have not been able to shut down the Big Uglies’ industrial capacity. Their weapons are primitive, but continue to be produced.”

He had once more the uneasy vision of a new Tosevite landcruiser rumbling around a pile of ruins just after the Race’s last one had been lost in battle. Or maybe it would be a new missile flying off its launcher with a trail of fire, and no hope of knocking it down before it hit.

Kirel said, “Our strategy of targeting the Tosevites’ petroleum facilities has not yet yielded the full range of desired results.”

“I am painfully aware of this,” Atvar replied. “The Big Uglies are better at effecting makeshift repairs than any rational being could have imagined. And while their vehicles and aircraft are petroleum-fueled, the same is not true of a large proportion of their heavy manufacturing capacity. This also makes matters more difficult.”

“We are beginning to get significant amounts of small-arms ammunition from Tosevite factories in the areas under our control,” Kirel said, resolutely looking at the bright side of things. “The level of sabotage in production is acceptably low.”

“That’s something, anyhow. Up till now, these Tosevite facilities have produced nothing but frustration for us,” Atvar said. “The munitions they turn out are good enough to damage us, but not of sufficient quality or precision to be useful to us in and of themselves. We cannot merely match them bullet for bullet or shell for shell, as they have more of each. Ours, then, must have the greater effect.”

“Indeed so, Exalted Fleetlord,” Kirel said. “To that end, we have recently converted a munitions factory we captured from the Francais to producing artillery ammunition in our calibers. The Tosevites manufacture the casings and the explosive charges; our only contribution to the process is the electronics for terminal guidance.”

Something Atvar said again. “But when our supply of seeker heads runs out-” In his mind that ugly smoke-belching landcruiser came out from behind the pile of ruins again.

“Such stocks are still fairly large,” Kirel said. “Again, we now have factories in Italia, France, and captured areas of the U S A and the SSSR beginning to turn out brakes and other mechanical parts for our vehicles.”

“This is progress,” Atvar admitted. “Whether it proves sufficient progress remains to be seen. The Big Uglies, unfortunately, also progress. Worse still, they progress qualitatively, where we are lucky to be able to hold our ground. I still worry about what the colonization fleet will find here when it arrives.”

“Surely the conquest will be complete by then,” Kirel exclaimed.

“Will it?” The more Atvar looked ahead, the less he liked what he saw. “Try as we will, Shiplord, I fear we shall not be able to prevent the Big Uglies from acquiring nuclear weapons. And if they do, I fear for Tosev 3.”

Vyacheslav Molotov detested flying. That gave him a personal reason for hating the Lizards to go along with reasons of patriotism and ideology. Ideology came first, of course. He hated the Lizards for their imperialism, for the efforts to cast all of mankind-and the Soviet Union in particular-back into the ancient economic system, with the aliens taking the role of masters and reducing mankind to slaves.

But beneath the imperatives of the Marxist-Leninist dialectic, Molotov also despised the Lizards for making him fly here to London. This trip wasn’t as ghastly as his last one, when he had flown in the open cockpit of a biplane from just outside Moscow to Berchtesgaden to beard Hitler in his den. He’d been in a closed cabin all the way-but he’d been no less nervous.

True, the Pe-2 fighter-bomber that had brought him across the North Sea was more comfortable than the little U-2 he’d used before. But it was also more vulnerable. The U-2 seemed too small for the Lizards to notice. Not so the machine he’d flown in yesterday. If he’d gone down into the cold, choppy gray water below, he knew he wouldn’t have lasted long.

But here he was, at the heart of the British Empire. For the five major powers still resisting the Lizards-the five major powers which, before the Lizards came, had been at war with one another-London remained the most accessible common ground. Large parts of the Soviet Union, the United States, and Germany and its European conquests lay under the aliens’ thumb, while Japan, though like England free of invaders, was next to impossible for British, German, and Soviet representatives to reach.

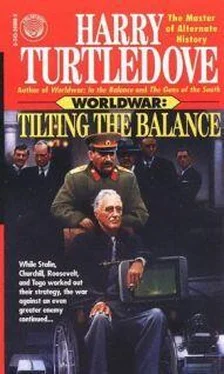

Winston Churchill strode into the Foreign Office conference room. He nodded first to Cordell Hull, the American Secretary of State, then to Molotov, and then to Joachim von Ribbentrop and Shigenori Togo. As former enemies, they stood lower on his scale of approval than did the nations that had banded together against fascism.

But Churchill’s greeting included all impartially: “I welcome you, gentlemen, in the cause of freedom and in the name of His Majesty the King.”

Читать дальше