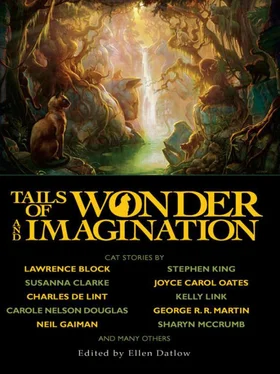

Ellen Datlow - Tails of Wonder and Imagination

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Ellen Datlow - Tails of Wonder and Imagination» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2010, ISBN: 2010, Издательство: Night Shade Books, Жанр: Фэнтези, Фантастика и фэнтези, Ужасы и Мистика, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Tails of Wonder and Imagination

- Автор:

- Издательство:Night Shade Books

- Жанр:

- Год:2010

- ISBN:978-1-59780-170-6

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Tails of Wonder and Imagination: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Tails of Wonder and Imagination»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

collects the best of the last thirty years of science fiction and fantasy stories about cats from an all-star list of contributors.

Tails of Wonder and Imagination — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Tails of Wonder and Imagination», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

We went into an old-fashioned smoking-room after dinner, with the brandy and cigarettes—it was a tradition of Arthur’s, because smoking otherwise was permitted everywhere about the house.

The velvet curtains were drawn, and another fire sparkled. Everything all told was very appealing and comfortable. Had it not been for the constant sense of unease and alertness—most like a vague, almost undetectable smell—that also hung over virtually every instant. Even Arthur’s relaxed periods had begun to seem forced. What was bothering him? I had come to the conclusion, whatever it was, it would be the very same matter that had prompted him to invite me to his home. I’m afraid I felt quite irritable at this. Once tomorrow dawned, I would have my hands full with the theatrical event in the town, and little time for sudden extra dramas.

Throughout dinner we’d spoken only of trivial things, mostly to do with the family. Arthur had remarked that I resembled my grandfather, when young, which I valued. In him, although I didn’t say so, I could see no likeness to any of our tribe.

Once in the smoking-room, a silence drifted down. We sat in armchairs, and Arthur stared long into the fire. And I thought, by now highly apprehensive myself, any minute and he’ll come out with it. Whatever the hell it is. And then let’s hope it can be put right very simply. Otherwise it must wait until the play is done.

Arthur said, again, “Yes, I can see my father in you. My brother must have grown to be a strong, well set-up young man. I know he can have been afraid of absolutely nothing. As a little child, even, he was fearless. I remember his nanny, the very woman who had terrified me as a child with her ghost stories, having no effect on him whatsoever.”

I said, “Yes, he was a brave man. I’ve seen as much myself from his war record.”

“Indeed. But I suppose,” said Arthur softly, “we are all of us, in the end, afraid of something. Otherwise, could we be human?”

“Certainly, I’m terrified of several things. The British tax system for one thing. Oh, and I admit, a certain well-known actress who shall be nameless.”

Arthur smiled, but the smile slipped off like water.

His face was closed-in, bent to the fire, his eyes viewing, it seemed, only that.

“Yes, but there are other fears, aren’t there? Inner fears. Fears located—how do they say it now—within the Id.”

I said nothing. This promised to be more weird and much more time-consuming than I’d supposed.

Arthur stirred the fire slowly with a poker. Then he sat there, holding the poker loosely in his hand.

“Since I was a boy,” he said, “since then, about six years of age. Something. I saw it first in a book, one of those stupid highly-coloured old illustrated books for children. Though I’d guess now it was meant for a much older child than I then was. It was on a low table, in the library. Thinking back, I believe it must have been my father’s property, when he was little. Had it terrified him? Apparently not. And why anyway was it lying out open where I could find it? I’ve often wondered that. I’d think, really, almost any child might have been frightened by it. The drawn picture—was very crude, all reds, yellows, blacks—horrible—” He raised his eyes straight up to mine. And they were full of utter terror, that glowed like tears. “I know now it was a book about Ancient Rome. And this picture concerned the Emperor Nero’s habit of having Christians thrown into the arena, and savage hungry animals let loose on them. An awful subject to illustrate. Probably meant to be improving. But me it did not improve. I rather think,” he lowered the poker slowly back into its place, “it ruined me.”

I was then, and am, no psychiatrist. I said, no doubt with inappropriate foolishness, “Of course, as a child, you might be afraid at it. But—how can it have ruined you?”

“I’d been quite a bold little boy. Always in scrapes. Brave. I used to lead a little local gang. We had some piratical name. But after I saw in that book—after I saw that picture, a change came over me. I used to dream, you see. I used to dream over and over about the picture.”

“The Christians being killed in the arena by the animals.”

“Killed, and devoured. Yes. They were—” he hesitated, and the oddest small twist of a smile distorted his lips, “they were lions,” he said. And then again, “Lions.” As if to repeat the name took a great effort of will, which he must exert.

Something in how he had stirred the fire had upset the logs. It sank and darkened, and the room seemed to darken too, despite the electric lamps.

I said, encouragingly, “Well, what you describe could be enough to give any kid nightmares.”

“Perhaps. But I must explain. My dreams were very specific. I was in the arena, you see. I, as a child. And I was alone. Alone that was but for a huge, formless, faceless crowd shouting and baying all around me from the seats. And I would stand there on the sand, naked, shivering and afraid—sickeningly afraid—and then a kind of black hole would come in the side of the arena, and a lion would come out. Only one, you see. Only one.” Arthur stopped. He put his head into his hands, but not before I’d seen his face was now almost green.

“Don’t go on if it distresses—”

“I must go on,” he said. He lifted his head and brought his brandy to his mouth and gulped the lot. “One lion,” he said. “I know him so well. A huge ochre beast, with a vast black-ruffed head. There were bloody welts on his side—they must have whipped him up from the cages below—that filthy book showed all that too… Each of his eyes were like yellow-red coals. He stank. I could smell him. He stank of butcher’s meat. And then he ran towards me—right at me—and I stood there screaming—and as he leapt his great claws flashed like silver hooks—and I woke—always I woke—just before his weight could come down and his talons and teeth could go into me. Always. And always, screaming. It happened every night, yet only ever once—once every night. It happened once every night for a whole year. I was afraid to go to bed. I would make myself keep awake, sitting up in the darkness—but in the end always I fell asleep. And then I’d be in the arena, alone but for the crowd, and he would come, the lion. And he would run and leap and in that split second, when the rush of his stinking flesh and his claws already felt like a boiling wind across my body—I’d wake up. I would escape him.”

“My God,” I said. Finally, I thought, the elements of his fear had truly communicated themselves to me. As with a powerful acting performance, the catharsis of empathically induced emotion. I was shaken.

“Well,” Arthur said presently. “I must tell you why the dreams stopped. First my parents tried to laugh and tease me out of them. Then they tried to bully me out. You perhaps have wondered why I’ve been a stranger to my own family all these years. Partly it began there. I never forgave them for it, their crass lack of understanding. And though in later years I could grasp almost perfectly that it came not from cruelty, but from a genuine, if entirely misplaced, conception of how best to deal with me—the rift had widened and was too enormous to heal. However, long before that, when I was seven years old, I met a gypsy in our garden. He’d just walked in at the gate, and was going round to the back of the house with some tinker’s stuff he’d got for the kitchen. But seeing me, he pulled a face, and then called to me, quite politely and gently. Come here, young master. That was what he said. And for some reason, to him I went. I was by then a thin, pale-faced child, with rings under my eyes from never sleeping well. I must have looked haunted enough; our doctor had already apparently warned my father I might be in the early stages of some incurable malady—which idea alarmed mother, but my father scoffed at it, saying I was just in a silly mood, trying still to be a baby, and waking everyone by yelling every night. But the gypsy man stared into my face, and then he said, ‘I can make him go away. One day he will come back. But you’ll be a man then, and perhaps a man will have the strength to turn him off for good.’ I gaped at him, and because I’d been brought up a certain way, I feebly said to him, ‘What do you mean?’ ‘Hush now,’ he answered. Then he put his hand on my head. It felt scalding hot, his hand, and he breathed in my face, and his breath was bad, because I suppose, poor fellow, his teeth weren’t up to much. But somehow that didn’t repulse me. When he lifted his hand away, I felt something go with it. He said, ‘Done now. Not till you’re a man will it come back. Go and tell the cook you took a toy off me from my sack, and I’m owed half a shilling.’ I did what he said, and later I received a smacking from my father, who told me off for making the cook pay for a paltry toy for me. He asked where the toy was. I said it had broken, and my father said that served me right. He would have broken it if I had not. That night I crept up to bed, and sat there in the dark as usual, my back sore from the blows, and biting my hand to keep awake. But I kept thinking of the gypsy, too. And in the end I let go. I let go and I slept. I slept right through. It was the first night in a year I didn’t have the dream. But after that, night followed night without it. Gradually then my general health improved. I was soon at school, and began to lead my own boy’s life again. Although I was never as I had been before I saw the book. I hadn’t the stamina I had had, even though I’d grown older and bigger. I tended to weight rather than muscle, I had headaches and once or twice fainted, if I was too hot or cold, and sometimes in church. But the dream was entirely gone. Gone till I should be a man and have the strength to face it once more, and then be able to send it away, to turn it off for good. Nevertheless—I could never be reconciled to that word, that name, or if I saw any picture of them, even a fine painting. Or if it was in a lesson. In Latin, for example. I even fainted then, too. Something in Suetonius, I think it was, about the Roman Circus.”

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

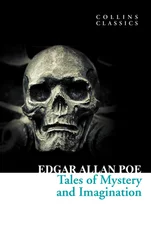

Похожие книги на «Tails of Wonder and Imagination»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Tails of Wonder and Imagination» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Tails of Wonder and Imagination» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.