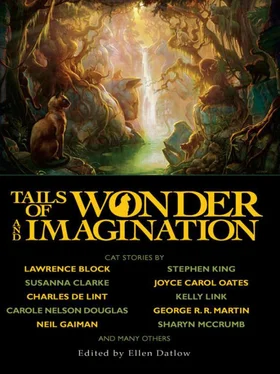

Ellen Datlow - Tails of Wonder and Imagination

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Ellen Datlow - Tails of Wonder and Imagination» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2010, ISBN: 2010, Издательство: Night Shade Books, Жанр: Фэнтези, Фантастика и фэнтези, Ужасы и Мистика, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Tails of Wonder and Imagination

- Автор:

- Издательство:Night Shade Books

- Жанр:

- Год:2010

- ISBN:978-1-59780-170-6

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Tails of Wonder and Imagination: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Tails of Wonder and Imagination»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

collects the best of the last thirty years of science fiction and fantasy stories about cats from an all-star list of contributors.

Tails of Wonder and Imagination — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Tails of Wonder and Imagination», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

“Rubbish,” I said. “Utter rot.”

Behind me, some entity stirred, a velvet sound, edged with something rasping and barbed. Like the noise of a cat, amplified.

I stood up and looked round again. Something was there. No doubt of it. In deep shadow, between the top of a wooden cupboard and the cornice of the ceiling. It looked most like a large full trunk. It hadn’t, I thought, been there previously.

My conclusion was that my Uncle Arthur had become insane, and was playing some type of bizarre, possibly dangerous, trick on me. I’ve had dealings with the unstable before—the profession on whose perimeter I work has presented to me some fine examples. To humour Arthur therefore seemed the best course.

Reluctant to stay with my back to whatever it was which had manifested in the corner, I moved my chair to a different angle, before sitting back down.

“Very well,” I said. “But you’ve got your answer to it, haven’t you? Cast out fear. Then it will go.”

“I try,” he said. “I try. It’s a war that never stops. That gypsy man who helped me in my childhood, he thought I might eventually prove the stronger, and the victory be mine. Or maybe that was only his pretense, because he could foresee what was more likely. I try, and try, and try. But the fear never goes. How can it? The evidence of what there is to fear is frequently in front of me. Besides, by now, I believe it is less fear—than how mighty that fear it has already fed on has made the—creature. How else has it done what it has? Perversely, at last, it’s only in sleep I ever evade it. Others here,” he said, with a weary, flat, matter-of-factness, “see the thing too. Oh yes, that’s how actual, despite my resistance, it has become. They see it. As you just did over there, up by the ceiling. And look now, the shadow on the carpet moving, the tail of it wagging slowly to and fro.”

I stared resolutely into the fire. Behind me, far off, vague, I heard a kind of soft grumbling guttural, that might only be some freak sound of the autumn wind in the chimneys.

“You should pack up and leave this house,” I said, lighting another cigarette.

“It would go with me,” he said. “By now it goes with me always. Sometimes it disappears, as if it has other little tasks it likes to see to about the place. Then it’s there again. My housekeeper has seen it. You can ask her. She’s decided it’s the ghost of a dog that once lived here. And my butler. The cook and maids somehow generally refuse to see it. Those that do sometimes complain of a large cat that has got into the main house from the kitchen.”

There was a long, slipping, heavy noise.

Arthur’s eyes went over above me. I saw him watch something move quickly across the upper air. His face was green again, but again he smiled. He nodded. He said, “It’s gone for the moment. I could see them then, the welts on its side. Poor thing. It must suffer. Poor damnable thing.”

I’d had enough. I got up again and said, “Sir, I have a very busy schedule, which begins quite early tomorrow. I understood you were aware of that when you invited me here. This matter, whatever it is, is beyond me. I don’t know what you expect me to do.”

“Only to listen. What else is feasible? I’d ask you to shoot it, if that were any good. But how could it be? It came out of the dark inside me. The dark where we go in dreams. It wants to take me back there, to keep me, to play with perhaps, or only to fulfill its function. Rend me. Devour me. Like the hapless Christians in the book.”

“You’ll have to excuse me,” I said. “It’s midnight. Perhaps I could ring for your man… Do you have any opiates to help you sleep?”

“Yes, go to bed,” Arthur replied. His face was icy with disgust.

I stood in the doorway of the smoking-room. The hall outside was rosily low-lit from a single lamp standing on a table. At the curve of the staircase, one of the maids was crossing, with an armful of what looked like table linen, to the baise door giving on the servants’ area. I looked at her, her trim brisk figure, and how, just before she reached the baise, something loped across her path, from shade to shadow, and she hesitated, as if to check the fall of one of the pile of linens she held, which were not slipping at all.

I saw its eyes gleam, fitfully. It glanced at me, indifferent. In its half-seen, solid shape was all the intangible presence of the night. But as he had said, it was an indoor beast, a beast of locked houses that left only one door open for it, in the frantic hope it might go out and lose itself. A beast too of the indoors of the brain, the psyche. A beast of the indoors of the human soul.

Like a scene from a play, I saw it, his dream, and how the beast leapt at him, missed him, always missing, as he fled outward to the world. And then his fear coming out of him, rejected, but still inextricably attached. Externalized.

The lion had gone around the corner and the maid passed through the servants’ door and the hall was empty.

I walked back into the smoking-room. He was sitting quietly crying, poor old child, with the welts of horror blistering on his side.

“All right, old chap,” I said. “All right.”

“I don’t,” he said, apologetically, “want to be alone.”

“Then you shan’t be. Hang the theatre. I’ll deal with it tomorrow.”

After a while, we went upstairs, and along one of the corridors to his room. Nothing was about, all was silence, and in the cracks of windows, where curtains didn’t quite meet, a low moon floated on a cloud.

We had another brandy, and he went to bed, or at least lay down with the coverlet over him. His round fallen face on the pillows stared at me.

“Nothing can be done. I know that,” he said. “When it comes back—”

“I’ll wake you,” I said. “Sleep for now.”

I’d asked myself if it could come in when he slept, but of course it could, that was the whole point to it now. It was in the world, and outside of him. And his former fear of meeting it in his mind had been replaced, not unreasonably, by the fear it would eventually seize him while he slept.

The electric light on the upper floors was dimmer. I sat in an armchair in this duller glow, and midnight passed into one, and so on through two. I smoked, and watched the clock, and wished I’d thought to bring some coffee upstairs.

But even so, I was wide awake. Arthur slept, deep and dumb. He might have been dead, I couldn’t help thinking that. I had no inspiration of what I could do. Keep the creature off him, then in the morning drive him somewhere, look up any one of a number of people who dealt in fractured minds and hallucinations—God knows. The brain ticks away in its backrooms often, and we’re unaware of its secret progress. I sincerely hoped it might offer me a plan, but hadn’t much faith it could.

For I knew too, of course I did, this now was more than a dream or mirage. I’d seen it. I’m prosaic enough, and it was merely pragmatic now to admit to having seen it. To deny the situation further would be to enter myself the lists of the fanciful or mad.

It returned when the clock said a quarter past three.

It came up through the floor.

That was like a stage effect, something clever with traps and levers, but involving no dry ice to mask it.

Arrived, it shook itself. The housekeeper had convinced herself it was a phantom dog, and there was something doglike about it certainly, as there often is with the big cats; tigers, panthers, and the rest. But its face was savage and evil, its eyes two mindless sumps of decayed fire that seemed to have given off the smoke of its mane. It did faintly stink, as he’d said. How had he known, as a child, what it might smell of? But perhaps lions don’t smell of meat; it was only something he’d heard and so made this one do it. For it was all his own work—his, and that of the artist who first so luridly depicted it and its kind, in the arena of Nero.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Tails of Wonder and Imagination»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Tails of Wonder and Imagination» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Tails of Wonder and Imagination» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.