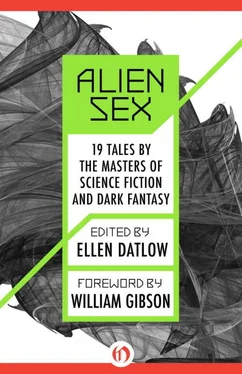

ALIEN SEX

19 Tales by the Masters of Science Fiction and Dark Fantasy

Edited by Ellen Datlow

FOREWORD: STRANGE ATTRACTORS

WILLIAM GIBSON

THIS FAR INTO THE twentieth century, writing science fiction or horror about sex is a tricky proposition. A vast and growing number of the planet’s human inhabitants have been infected with a sexually transmitted virus of unknown origin, a terminal disease for which there is no known cure. Considered as a background scenario, this situation is so unprecedentedly grim as to send the bulk of science fiction’s folk-futurists, myself included, cringing and yelping back to our warp drives and all the rest of it.

Beam us up, Scotty. (Please.)

Chaos theory, the hot new branch of science that reads as though it tumbled intact from the womb of some vast unwritten Phil Dick novel, suggests that the human immune system currently finds itself in the vicinity of a “strange attractor.” Which is to say that the biochemical aspect of humanity dedicated to distinguishing self from other is already on a greased slide known as the “period-doubling route to chaos,” wherein things get weirder and weirder, faster and faster, until things change, quite utterly, signaling the emergence of a new order. Meanwhile—if there can be a meanwhile in chaos theory—we have real-life scientists intent on downloading human consciousness into mechanical “bodies,” injecting subcellular automata into bodies of the old-fashioned kind, and all that other stuff that makes it so hard for science-fiction writers to keep up with the present.

Against that kind of global backdrop, how do you go about writing fiction about the alienness of sex?

A look at the history of horror fiction may provide a partial answer. Bram Stoker’s Dracula is a horror story about sex, a Victorian shocker centered on dark drives and addictions of the flesh. H. P. Lovecraft, in his cranky neo-Victorian way, went a similar route, though he lacked Stoker’s physicality, Stoker’s sense of lust, so that all those oozing floppity horrors from the basements of Arkham seem finally to suggest the result of playing around under the bedclothes. Stephen King, retrofitting the horror novel for the age of MTV, cannily targeted the bad thing, the central obscenity, the dark under all our beds, as death. Sexual paranoia can still do yeoman duty producing narrative traction, but the thought that we ourselves are sexual beings has lost its power to make us shudder and turn pages.

In the post-King era of horror fiction, we find Anne Rice, whose sulkily erotic reading of Stoker finally brings the potent S&M aspect of the vampire text into overt focus, and Clive Barker, whose postmodern splatter-prose often overlays a disturbingly genuine insight into the nature of human sexual dependence. Rice and Barker have both used horror, to some extent, as an exploratory probe, a conscious technique owing more to modern science fiction than to the pre-Freudian nightmares of Stoker or Lovecraft.

Think of the stories assembled in this collection as exploratory probes—detectors of edges, of hidden recesses, of occluded zones, of the constantly shifting boundaries between self and other, of strange attractors and their stranger fields of influence. Because these are things we speak of when we speak of sex, whether in the best of times or the worst.

SEXUALITY, HUMAN OR OTHERWISE, has not traditionally been a major concern in science fiction—possibly because the genre was originally conceived for young adults. However, there was some early pioneering in the field. In 1952 Philip José Farmer explored the theme of interspecies love and sex in “The Lovers” and Theodore Sturgeon examined the nature of sexual roles in Venus Plus X (1960). Then, during the late 1960s and the 1970s, more science-fiction writers began to explore the issues of sexuality and relationships, and authors such as James Tiptree, Jr. (“The Women Men Don’t See”), Ursula Le Guin (The Left Hand of Darkness), Samuel R. Delaney (Dhalgren), Norman Spinrad (Bug Jack Barron), Brian Aldiss (Hothouse), and J. G. Ballard (Crash) wrote major works that treated the subject of sexuality seriously and occasionally explicitly. Part of the reason Harlan Ellison’s anthologies Dangerous Visions and Again Dangerous Visions were such breakthrough volumes was their inclusion of stories on previously taboo subjects. There have been three previous SF anthologies on sexual themes: Strange Bedfellows: Sex and Science Fiction, edited by Thomas N. Scortia (1972); Eros in Orbit, edited by Joseph Elder (1973); The Shape of Sex to Come, edited by Douglas Hill (1978), and a collection, Farmer’s Strange Relations (1960).

Sex in SF generally deals more often with the obsessions of human sexuality and relationships than it does with actual human-alien sex. For example, John Varley’s story “Options” created a society in which anyone could choose to alter their sexuality, physically and emotionally, at will. Le Guin’s novel The Left Hand of Darkness, while concentrating on gender and its relationship to social and sexual roles, incidentally created the perfect sexuality: the inhabitants of the planet Winter are an androgynous species. During their periodic sexually active phase, they can alter their sexual identities to complement the person to whom they are attracted.

When I first had the idea for this anthology, I honestly intended it to be stories specifically about “alien sex,” concentrating on the alien as in “other world.” But as the book began to take shape, I realized that what the material was really about was the relationships between the human sexes and about how male and female humans so often see each other as “alien”—in the sense of “belonging to another country or people; foreign; strange; an outsider” (Webster’s New World Dictionary of the American Language, college edition, 1966). Alien Sex offers a template for human relationships.

The stories herein encompass many of the ways the sexes perceive each other and deal (or don’t deal) with each other, even when actual, off-world aliens are depicted. Most were written since the 1970s, when feminism changed forever the way men and women (in the United States at least) relate to one another. Since then, relationships between the sexes have continued to be in flux, making for “interesting times,” as in the ancient Chinese curse. What do women want? What do men want? Indeed, do we want the same things? Less from design than circumstance, the stories are roughly balanced between male and female writers. While I don’t think that on the whole this anthology is particularly downbeat, I do think it gives a rather dark view of male/female relationships. Obviously, both sexes feel this way, and perhaps that in itself lends hope to the future of human sexuality.

My greatest problem in putting together the anthology was to find the perfect title—the best in my view, Strange Bedfellows, had already been used. I came up with Dark Desires but was persuaded that it sounded too much like a Gothic romance. Then I asked various writers for suggestions. The following were offered: Inter s tellarcourse, Love with the Proper Alien, Love Without Feet, Love Is a Many-Headed Thing, Strange Bedthings, In Bed with Darkness, Close Encounters of Another Kind, Looking for Mr. Goodtentacle, Loving the Alien, Bems, Boobs & Bimbos, Fucking Weird, Bedrooms to the Stars, Dangerous Virgins —you get the idea. After much thought, my title of choice was Off Limits: Sex and the Alien. Unfortunately, when my agent submitted the anthology, she (and I, I admit) kept calling it the “alien sex” anthology, which led my editor at Dutton to refer to it that way to her colleagues. Everyone loved it and it stuck. Thus, you have the genesis of a very catchy title (after all, you do have the book in your hands, don’t you) for a thought-provoking book. The stories here may intrigue, horrify, and possibly offend you, but I guarantee they won’t bore you.

Читать дальше