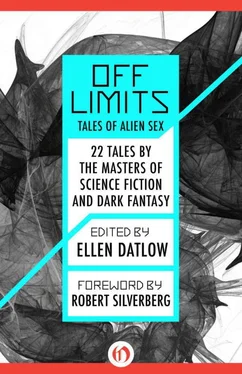

OFF LIMITS

Tales of Alien Sex

Edited by Ellen Datlow

Foreword

ROBERT SILVERBERG

THE ESSENTIAL THING TO keep in mind about sex is that its inherent purpose is to bring two alien beings together to create a third being different from them both.

I’m talking strict biology here, of course, taking things right down to the teleological nitty-gritty. Whatever sex may happen to mean to you or you or you or me, the inarguable fact remains that the whole sexual thing was programmed into most living organisms above the level of viruses and bacteria for the primary sake of bringing about an exchange of genetic material between two individuals who belong to the same species but otherwise may have very little in common—who resemble each other physically in a certain superficial way, but who have different identities and perceptual equipment, a whole array of different secondary physiological characteristics, and even, to some extent, different kinds of internal organs. (Some different external ones, too!)

That’s really at the bottom of it all, you know: moving those gametes around, getting sperm and egg together, bringing about fertilization, calling into being a single-celled zygote that carries one set of chromosomes from its male parent and another from its female one. If all goes well, cells divide, the zygote expands to become an embryo, and in time a new individual comes forth, carrying a mix of chromosomes that will cause it to resemble its parents in most major respects but to be, nonetheless, something new and unique.

This procedure, this business of sexual reproduction, is high-priority stuff indeed in the evolutionary scale of values. Without it, without the constant shuffling of genetic information that the meeting of gametes creates, species would never vary from one generation to the next. The newborn organisms would be exact replicas of their progenitors—carbon copies, xeroxes, backup disks, whatever metaphor you want to use. Exact replicas, that is, except for the inevitable entropie degradation that eventually would set in, comparable to the blurriness that occurs when you photocopy something that is already a tenth generation copy of the original document. There would be no evolution, no recombination of genetic matter to bring new and perhaps improved models of the organism into existence. There would only be the slow, steady slide for generation after generation toward looking like something that has been passed through the photocopy machines of ten different offices.

Nature takes the concept of sexual reproduction so seriously that it has programmed all these interesting pleasure-syndromata into us to make sure that we keep on doing it. No matter how we think about the need to have gametes meet and shuffle their chromosomes together, we tend to keep on engaging in sexual acts because doing so is, for most of us, an extremely enjoyable thing. (And, because we are highly evolved beings as a result of thousands of generations of combination and recombination of chromosomes, we have in relatively recent times cleverly figured out ways of receiving the pleasure without following through with the biological consequences. The childless but sexually active heterosexuals of the world, the homosexuals of various sorts, and many purely solitary folk as well, have all separated themselves from the business of gametes and zygotes but most assuredly are still paying attention to those hardwired pleasure impulses that were installed in them at the moment of conception to keep those moments of conception coming along.)

You see, I hope, where this line of reasoning is heading. Sex is an innate drive, put there for significant biological reasons; it impels each organism in a centrifugal fashion, outward from the center of its own biological boundaries to seek physical union with an organism that is fundamentally different from itself in many ways—that is, in fact, an alien being with its own identity, behavior patterns, and physical form; and human beings, although they are driven by this innate need just as much as nematodes and fruit flies and salamanders are, are such complex and ornery creatures that they have extended the definition of what is an acceptable sexual partner far beyond the innately prescribed one of same-species-other-sex. As the stories in this book demonstrate, we are capable of reaching quite far afield indeed.

But always—whether the love object is the girl or boy next door or some sleek aquatic being native to Betelgeuse XII—the process involves opening the boundaries of one’s being to something alien, something that is not-oneself, something that differs from oneself in a fundamental way. The chromosomes tell the tale. There is only one of me on this planet, and only one of you, because nobody else has my particular mix of genes, and nobody else has yours, and therefore we are really alien beings in respect to each other. Yet we each have something that the other wants; and so we come together, in trepidation and hope, attempting to transcend the boundaries that separate us from each other. Sometimes the effort is successful, sometimes not. In any case, it remains fundamentally true that all sexual encounters are meetings between aliens who must transcend the barriers of their alienness if they are going to attain any kind of union—whether they be those kids holding hands outside the movie theater or Mrs. Tompkins getting it on with the thing from the Aldebaran system during the interstellar cruise. As the stories you are about to read will demonstrate.

ALIEN SEX , PUBLISHED IN 1990, was not so much about aliens and sex but rather about human sexuality in all its strange forms and how men and women interact. It included about half reprints—classics from between 1968 and 1985, and half original stories written around 1989. Science fiction has traditionally been a bit hesitant about dealing with sexual and gender themes. There have always been notable exceptions—Philip José Farmer’s “The Lovers” (1952), Theodore Sturgeon’s Venus Plus X, and the writings of James Tiptree, Jr., Ursula K. Le Guin, Samuel R. Delany, Gardner Dozois, Joanna Russ, Brian W. Aldiss, and John Varley. But in the past ten years, science fiction seems to have become a hothouse of speculation on sexuality and gender. This may be a result of the AIDS crisis or the extraordinary breakthroughs in bioengineering; for whatever reason, there are more writers than ever before exploring and questioning sexuality in their work. Nicola Griffith, Michael Blumlein, Eleanor Arnason, Geoff Ryman, and Richard Calder are just a few of the newer ones.

In contrast to Alien Sex, more of the stories in Off Limits deal with the physical dangers of sex. There appears to me a more overt awareness of the AIDS crisis and how it affects our relations to one another. At least four stories in Off Limits take place in societies beset by sexual plagues and focus on the personal and political ramifications of these plagues for individuals and society at large. Paranoia looms large, it brings out the worst in people, and generally, those in power have not made what most of us would consider the right decisions dealing with the crises. Instead of finding cures they blame the victims (sound familiar?). Brian Stableford, Elizabeth Hand, and Mike O’Driscoll have all imagined worlds in which the worst future has happened and adjustments have been made—usually to the detriment of females.

One thread running through the stories in Off Limits is the “prostitute as protagonist”—the outsider, as independent woman, as whore; prostitution as a means to avoid entanglements. Who has the power in these relationships and why? Is prostitution honorable? Why do men (and occasionally women) feel they need to pay for sex? No matter one’s views, the oldest profession is inextricably tied to gender politics and is here to stay—although some writers see future prostitutes biologically enhanced with special pheromones or as living dolls. Another common thread is the third world serving as fodder for the more “civilized” world, with individuals using the beautiful and alien in unclean ways.

Читать дальше