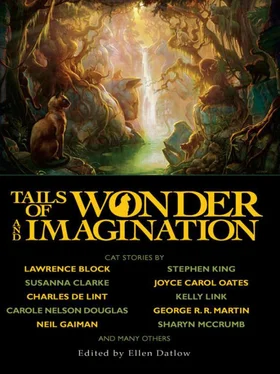

Ellen Datlow - Tails of Wonder and Imagination

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Ellen Datlow - Tails of Wonder and Imagination» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2010, ISBN: 2010, Издательство: Night Shade Books, Жанр: Фэнтези, Фантастика и фэнтези, Ужасы и Мистика, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Tails of Wonder and Imagination

- Автор:

- Издательство:Night Shade Books

- Жанр:

- Год:2010

- ISBN:978-1-59780-170-6

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Tails of Wonder and Imagination: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Tails of Wonder and Imagination»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

collects the best of the last thirty years of science fiction and fantasy stories about cats from an all-star list of contributors.

Tails of Wonder and Imagination — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Tails of Wonder and Imagination», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

“You sound like the old priest who taught me philosophy,” said Esteban. “His world—his Heaven—was also philosophy. Is that what your world is? The idea of a place? Or are there birds and jungles and rivers?”

Her expression was in partial eclipse, half-moonlit, half-shadowed, and her voice revealed nothing of her mood. “No more than there are here,” she said.

“What does that mean?” he said angrily. “Why will you not give me a clear answer?”

“If I were to describe my world, you would simply think me a clever liar.” She rested her head on his shoulder. “Sooner or later you will understand. We did not find each other merely to have the pain of being parted.”

In that moment her beauty—like her words—seemed a kind of evasion, obscuring a dark and frightening beauty beneath; and yet he knew that she was right, that no proof of hers could persuade him contrary to his fear.

One afternoon, an afternoon of such brightness that it was impossible to look at the sea without squinting, they swam out to a sandbar that showed as a thin curving island of white against the green water. Esteban floundered and splashed, but Miranda swam as if born to the element; she darted beneath him, tickling him, pulling at his feet, eeling away before he could catch her. They walked along the sand, turning over starfish with their toes, collecting whelks to boil for their dinner, and then Esteban spotted a dark stain hundreds of yards wide that was moving below the water beyond the bar: a great school of king mackerel.

“It is too bad we have no boat,” he said. “Mackerel would taste better than whelks.”

“We need no boat,” she said. “I will show you an old way of catching fish.”

She traced a complicated design in the sand, and when she had done, she led him into the shallows and had him stand facing her a few feet away.

“Look down at the water between us,” she said. “Do not look up, and keep perfectly still until I tell you.”

She began to sing with a faltering rhythm, a rhythm that put him in mind of the ragged breezes of the season. Most of the words were unfamiliar, but others he recognized as Patuca. After a minute he experienced a wave of dizziness, as if his legs had grown long and spindly, and he was now looking down from a great height, breathing rarefied air. Then a tiny dark stain materialized below the expanse of water between him and Miranda. He remembered his grandfather’s stories of the Old Patuca, how—with the help of the gods—they had been able to shrink the world, to bring enemies close and cross vast distances in a matter of moments. But the gods were dead, their powers gone from the world. He wanted to glance back to shore and see if he and Miranda had become coppery giants taller than the palms.

“Now,” she said, breaking off her song, “you must put your hand into the water on the seaward side of the school and gently wiggle your fingers. Very gently! Be sure not to disturb the surface.”

But when Esteban made to do as he was told, he slipped and caused a splash. Miranda cried out. Looking up, he saw a wall of jade-green water bearing down on them, its face thickly studded with the fleeting dark shapes of the mackerel. Before he could move, the wave swept over the sandbar and carried him under, dragging him along the bottom and finally casting him onto shore. The beach was littered with flopping mackerel; Miranda lay in the shallows, laughing at him. Esteban laughed, too, but only to cover up his rekindled fear of this woman who drew upon the powers of dead gods. He had no wish to hear her explanation; he was certain she would tell him that the gods lived on in her world, and this would only confuse him further.

Later that day as Esteban was cleaning the fish, while Miranda was off picking bananas to cook with them—the sweet little ones that grew along the riverbank—a Land Rover came jouncing up the beach from Puerto Morada, an orange fire of the setting sun dancing on its windshield. It pulled up beside him, and Onofrio climbed out the passenger side. A hectic flush dappled his cheeks, and he was dabbing his sweaty brow with a handkerchief. Raimundo climbed out the driver’s side and leaned against the door, staring hatefully at Esteban.

“Nine days and not a word,” said Onofrio gruffly. “We thought you were dead. How goes the hunt?”

Esteban set down the fish he had been scaling and stood. “I have failed,” he said. “I will give you back the money.”

Raimundo chuckled—a dull, cluttered sound—and Onofrio grunted with amusement. “Impossible,” he said. “Incarnación has spent the money on a house in Barrio Clarín. You must kill the jaguar.”

“I cannot,” said Esteban. “I will repay you somehow.”

“The Indian has lost his nerve, Father.” Raimundo spat in the sand. “Let me and my friends hunt the jaguar.”

The idea of Raimundo and his loutish friends thrashing through the jungle was so ludicrous that Esteban could not restrain a laugh.

“Be careful, Indian!” Raimundo banged the flat of his hand on the roof of the car.

“It is you who should be careful,” said Esteban. “Most likely the jaguar will be hunting you.” Esteban picked up his machete. “And whoever hunts this jaguar will answer to me as well.”

Raimundo reached for something in the driver’s seat and walked around in front of the hood. In his hand was a silvered automatic. “I await your answer,” he said.

“Put that away!” Onofrio’s tone was that of a man addressing a child whose menace was inconsequential, but the intent surfacing in Raimundo’s face was not childish. A tic marred the plump curve of his cheek, the ligature of his neck was cabled, and his lips were drawn back in a joyless grin. It was, thought Esteban—strangely fascinated by the transformation—like watching a demon dissolve its false shape: the true lean features melting up from the illusion of the soft.

“This son of a whore insulted me in front of Julia!” Raimundo’s gun hand was shaking.

“Your personal differences can wait,” said Onofrio. “This is a business matter.” He held out his hand. “Give me the gun.”

“If he is not going to kill the jaguar, what use is he?” said Raimundo.

“Perhaps we can convince him to change his mind.” Onofrio beamed at Esteban. “What do you say? Shall I let my son collect his debt of honor, or will you fulfill our contract?”

“Father!” complained Raimundo; his eyes flicked sideways. “He…”

Esteban broke for the jungle. The gun roared, a white-hot claw swiped at his side, and he went flying. For an instant he did not know where he was; but then, one by one, his impressions began to sort themselves. He was lying on his injured side, and it was throbbing fiercely. Sand crusted his mouth and eyelids. He was curled up around his machete, which was still clutched in his hand. Voices above him, sand fleas hopping on his face. He resisted the urge to brush them off and lay without moving. The throb of his wound and his hatred had the same red force behind them.

“…carry him to the river,” Raimundo was saying, his voice atremble with excitement. “Everyone will think the jaguar killed him!”

“Fool!” said Onofrio. “He might have killed the jaguar, and you could have had a sweeter revenge. His wife…”

“This was sweet enough,” said Raimundo.

A shadow fell over Esteban, and he held his breath. He needed no herbs to deceive this pale, flabby jaguar who was bending to him, turning him onto his back.

“Watch out!” cried Onofrio.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

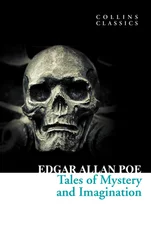

Похожие книги на «Tails of Wonder and Imagination»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Tails of Wonder and Imagination» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Tails of Wonder and Imagination» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.