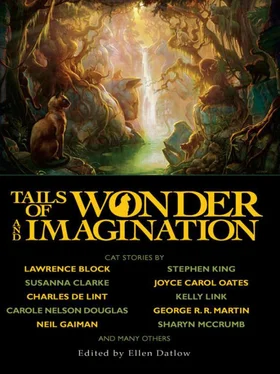

Ellen Datlow - Tails of Wonder and Imagination

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Ellen Datlow - Tails of Wonder and Imagination» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2010, ISBN: 2010, Издательство: Night Shade Books, Жанр: Фэнтези, Фантастика и фэнтези, Ужасы и Мистика, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Tails of Wonder and Imagination

- Автор:

- Издательство:Night Shade Books

- Жанр:

- Год:2010

- ISBN:978-1-59780-170-6

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Tails of Wonder and Imagination: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Tails of Wonder and Imagination»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

collects the best of the last thirty years of science fiction and fantasy stories about cats from an all-star list of contributors.

Tails of Wonder and Imagination — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Tails of Wonder and Imagination», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

And as she gazed at him, her face reddened even more, though not from fear or pain. The poet took the sumi ink and stared back at her musingly.

She is nothing like Fair Flower, Ga-sho thought. There is no fragrance here but the reek of boiling fish guts, and her hands are black as my cat’s paws, and her skin is as red as—well, as red as Clean-ears’s fur. And everyone says the old man beats her…

And yet her smile was sweet, her voice low, her gaze gentle. And she had shown kindness to a stray cat….

“Thank you,” he said, too quickly, then turned and left.

That night Ga-sho wrote a poem in praise of the inkmaker’s daughter. He could not, in good conscience, compare her to a flower, or even a blossoming weed. But the Japanese have many poems that honor cats, and so he began by comparing her to Clean-ears. After some time spent thus, his thoughts began to move from feline virtues to more feminine ones, and he found himself composing verse that (to his own mind, at least) was at least as fine as those poems inspired by Fair Flower. He recited the best of these several times to Clean-ears, who sat washing her paws (which became no whiter than Ukon’s palms) beside the lamp.

Red cheek, raven hair,

Her hands night-shaded and raw—

I would know her name!

He took a sheet of paper, withdrew the sumi stick he had bought that afternoon, and unwrapped it.

“Ah!”

The poet’s eyes grew wide and wondering. He held up the blossom-shaped ink block, glossy, with a telltale reddish tinge. He felt his cheeks grow hot, and looked furtively aside at the cat, as though to make sure she did not notice his blush.

But the cat was gone. And so, smiling to himself as he ground the vermillion ink on his inkstone and licked the sable tip of his brush, Ga-sho began to record his poem.

Meanwhile, Ukon was waiting up for her stepfather in the back of the shop, where her bed was a thin pallet on the floor. She dared not sleep before he returned; in any event, her thoughts were too full of the young poet to be at rest. So she busied herself tending the small hearth that heated the shop, and removing dry sumi sticks from their rice husks and wrapping them in paper.

It was past midnight when she heard the sound of stumbling footsteps in the alley, followed by the creaking of the door as it was pulled open.

“Father,” she called softly, going to greet him.

Her stepfather stumbled into the room, robes awry and his thin hair disheveled. Ukon drew up alongside him, trying to help him keep from falling.

“Lazy bitch!”

He struck at her furiously, but in his drunkenness he went flailing wildly, bashing against one thin wall. Ukon ran to his side, but he lashed out at her again, striking her so that she fell, weeping, by the hearth.

“You have been seeing men in here,” he gasped, struggling to his feet. “The old woman next door said she saw that layabout from the next street—”

“He was a customer, most watchful of stepfathers,” Ukon pleaded. “You must remember him, he is the poet—”

“Poet! He is worthless, as you are! Whoring like your mother before you!”

But at the word “customer” his eyes had gone to the metal strongbox where each day’s accounts were kept. He grabbed it, shaking it; opened it, then glared accusingly at Ukon.

Oh no! She covered her face with her hands. Her delight in serving the young poet had blinded her to duty—she had forgotten to get payment for the ink stick!

“Father,” she stammered, but it was too late. He began beating her with the strongbox, battering at the poor girl’s face and shoulders until she collapsed onto the floor in a heap.

“I will find this poet and kill him,” she heard her stepfather mutter thickly as he flung the metal box aside. “That I will…”

Ukon was too weak to do more than pull herself to a corner, watching through swollen eyes as her stepfather lurched out the back door into the alley. But soon sheer exhaustion washed over her pain, as with time the tide will cover a littered beach, smoothing out the soiled sand and, for a little while at least, making the world seem at peace. So it was that Ukon fell into fitful sleep upon the dirt floor, one arm still flung protectively over her poor battered face.

She woke to a low voice calling her name.

“Ukon… Ukon, you must wake!”

She raised her head groggily, the torn sleeve of her robe catching on the edge of a small table, and looked up. In her dreaming she had half-imagined the voice belonged to the young poet.

But as she blinked in the darkness she saw a woman standing before her. She was older than Ukon, her neat coif showing wisps of gray beneath thick black hair lacquer; for an instant, Ukon thought it was her mother. Then she saw that while the woman’s pointed face had the same piquance as her mother’s, her eyes were a very pale gray, like seawater, and she wore a kimono of deep scarlet silk, a color her mother would never have worn.

“You must come with me,” the woman said, calmly but with great urgency. As Ukon began to stammer a question, she raised a hand, its palm smudged as black as Ukon’s own. “There is no time—come!”

Ukon got to her feet. Her ears rang from the blows her stepfather had given her, and she thought she could hear another sound, oddly familiar, but the strange woman did not give her the opportunity to look around the shop for its source.

“This way!” she hissed; grabbing Ukon’s wrist, she dragged her out to the street. They began running along the narrow way, their wooden shoes sliding in the sleet and dirty snow. As they ran, Ukon began to hear agitated voices behind her, and then a sudden shout.

“Fire! The inkmaker’s shop is on fire!”

“Aiie!” With a cry, Ukon stopped and looked back. From the alley behind her stepfather’s shop rose a plume of smoke. Abruptly the wind shifted, carrying the smell of burning pine. “He must have overfilled the stove in the shed! I must go—”

“No.” This time the woman’s voice was a command. Her hold on Ukon’s wrist tightened. Her breath as she pulled the girl to her smelled of rotting fish. “Your life there is over. You will come with me now. Do not look back again.”

In a daze, Ukon turned and let herself be led along twisting alleys, away from the inkmaker’s shop. A great clamor of gongs and bells now arose from the streets, as people signaled that the quarter was in danger of burning; as dozens of men raced toward the shop carrying wooden buckets of water and sand, few noted the inkmaker’s stepdaughter hurrying in the opposite direction, a small red cat at her side. Afterward, those who had seen her running displayed neither recrimination nor much remorse for her leaving her stepfather to perish in the flames. His cruelty and drunkenness were well-known; the fire, which had indeed started in the shed, was contained to his quarters, and no one else was harmed.

Ukon followed the strange woman to a narrow street where she had never been.

“Here,” the woman said, bowing as she gestured at the door. “Here you will find safety.”

And before Ukon could protest, or give voice to her questions, the woman was gone. The poor girl stood shivering in the snow, tears once more springing to her eyes, when suddenly the little door slid open, and who should be standing there, yawning and rubbing his face, but the young poet, Ga-sho.

“Why…?” He stared at her in disbelief. Ukon dropped her head, abashed and ashamed, and had begun to turn away when he grabbed her hand. “Don’t go! Please, come in. You look half frozen, and”—his voice dropped, and he chuckled—“and look who you’ve found! Kury-ri, you naughty creature…”

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

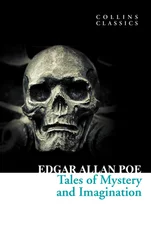

Похожие книги на «Tails of Wonder and Imagination»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Tails of Wonder and Imagination» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Tails of Wonder and Imagination» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.