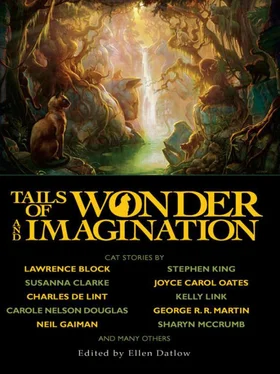

Ellen Datlow - Tails of Wonder and Imagination

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Ellen Datlow - Tails of Wonder and Imagination» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2010, ISBN: 2010, Издательство: Night Shade Books, Жанр: Фэнтези, Фантастика и фэнтези, Ужасы и Мистика, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Tails of Wonder and Imagination

- Автор:

- Издательство:Night Shade Books

- Жанр:

- Год:2010

- ISBN:978-1-59780-170-6

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Tails of Wonder and Imagination: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Tails of Wonder and Imagination»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

collects the best of the last thirty years of science fiction and fantasy stories about cats from an all-star list of contributors.

Tails of Wonder and Imagination — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Tails of Wonder and Imagination», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

The red cat slept beside Ga-sho and kept him warm at night. In the morning, she gently woke him by nudging his cheek. When the poet ate, he always saved bits of fish for his companion. When he had little money for food, or forgot to eat, Clean-ears would slip silently as a sigh from his tiny room and make her way to the city docks. An hour or so later she would return, bearing a fish, or perhaps a prawn, that she would lay upon the poet’s wooden pillow. Always she would politely refuse to dine until he was finished, and in return he was careful to save for her the choicest parts of the head, particularly the eyes, to which the red cat was very partial.

One of the few people Ga-sho could afford to do business with was an inkmaker whose shop was not far from the poet’s cramped room. The inkmaker was a poor man himself, but poverty had made him neither kindly nor patient toward those who owed him money. Rather, he was mean-spirited, craven to those with more wealth than his meager savings, and to one person at least he was downright cruel.

This was his stepdaughter, Ukon. He had married her mother under the misprision that she had a small fortune; upon discovering that she did not, he had hounded her to her death (or so it was believed in that part of the city, where gossip ran hot and destructive as the fires that often broke out during the winter months). Ukon’s mother was also reputed to have been a fox-fairy, and for several weeks after she died the inkmaker kept a cudgel by his bed, in case her vengeful spirit returned to harm him.

But either because she was not a fairy, or because she feared for her daughter’s well-being, the ghost did not appear, and poor Ukon was left alone to her fate. Neighbors could hear her piteous cries late at night when her stepfather beat her—bamboo-and rice-paper walls do little to hide such things—but no one moved to help her. A man’s daughter, even a stepdaughter, was his own concern. So, as her father spent his days and nights drinking with his customers and creditors, the brunt of the work of making ink was left to his stepdaughter.

It was Ukon who tended to the small stove where red pine wood and red pine resin were burned, all through the autumn and winter months. It was Ukon who then scraped the resulting soot from inside the stove, placing it in a bowl to which she added fish glue. The fish glue she made herself, begging fish bones from the docks, then boiling them on another stove. It smelled horrible, so she added plum and peony blossoms, and sometimes even sandalwood, if she could afford it. She mixed the fish glue and the soot together on a wide wooden plank, kneading the thick paste until it became soft and pliable as sweet rice cakes, then pressed the soft ink into wooden pattern blocks, square and round and rectangular. But the ink could not be left in the pattern molds, or it would crack as it dried. Ukon had to very carefully remove the blocks of ink, transferring them to wooden boxes filled with damp charcoal. Here the sumi ink would dry slowly, for days or even weeks, and Ukon had to replace the charcoal as it dried. Finally the sumi was dry enough to be wrapped in rice paper and hung to cure for another month, in the little shed in the alley behind the shop where she and her stepfather lived. Only then would Ukon carefully mark each sumi stick with her stepfather’s mark, wrap it in fine paper, and pile them all in neat stacks in the rear of the little shop. Her hands and fingers had become so stained by sumi ink that they never washed clean, nor did the rank smell of fish bones ever leave her skin; rather than help her, though, her drunken stepfather only mocked the girl.

“You will never win a suitor,” he said disdainfully, staring at her black hands. “I will be lucky if you don’t frighten away the few customers we have—”

And he cuffed her fiercely on the cheek, sending her reeling back to where the largest ink blocks awaited cutting.

Now, I have written that no one ever moved to help Ukon, but that is not quite true. Because the girl, poor and miserable as she was, yet possessed a kind heart, and like the half-strangled rosebush that still reaches toward a thread of sunlight, so did Ukon strive toward charity. As there was not a single human being in that quarter as poor and unhappy as she, Ukon’s kindnesses by necessity were directed toward other creatures, smaller and even hungrier than herself. So she would rescue crippled crickets trapped in their bamboo cages when the boys grew bored with them and tossed them aside, and save grains of rice to feed half-starved sparrows in the winter snow. And she would secretly feed a cat that often showed up in the alley behind the shop, a small red cat with a puffy bobbed tail like a blossom past its prime. It was drawn like other strays by the smell of rotting fish that rose from the ink shed. But it was smaller than the other cats, and milder-tempered, and Ukon made a point of saving fishtails for it, and fish bones with bits of flesh still adhering to them like hairs to a brittle comb.

It was on one such afternoon, late of a winter day in the Eleventh, or Frosty, Month, that Ukon made one of her furtive forays into the alleyway.

“Ah, suteneko,” she crooned, stooping to stroke the red cat behind its ears. “Poor suteneko, pretty Kinkwa-neko —you are so cold! Here—there is hardly anything, but…”

She held out her ink-blackened fingers, and the cat licked the flakes of fish from them gratefully.

“She’s not a stray, you know.”

Ukon whirled, frightened, and backed against the flimsy wall of the shed. She lowered her head automatically, as she would in deference to any customer, but she also raised her arm, as though to protect herself from a blow.

Peering through her fingers she saw not the threatening figure of her drunken father, but a young man in frayed robes and worn wooden shoes.

The poet, she thought, recognizing him by the ink stains on his sleeves and his hollow cheeks. Slowly she lowered her hand, but remained where she huddled against the wall, heedless of the sleet pelting down on her bare head.

“She stays with me,” the poet went on matter-of-factly. “ Suteneko!” he said chidingly, and bent to pick up the cat. “She thinks you’re a stray!”

He stroked her head, blowing into her pointed ears, then looked at Ukon. “I call her Kuri-ryoumimi,” he said. “Kury-ri.”

“Ah.” Ukon smiled tentatively “‘Clean-ears.’”

The poet smiled back at her. But his smile died as he took in her blackened hands and red face—red and chafed from crying, and still bearing the marks of her stepfather’s blows. “I… I was in the shop, but saw no one,” he said apologetically. “I need some more ink. But I can come back tomorrow—”

“No, no,” Ukon cried, and hurried back inside. “My father is gone on an errand”—in fact, he was drinking at the tavern—“but I will get whatever you need.”

She busied herself with finding and wrapping several rectangular blocks of ink. The poet had asked for the cheapest kind, which was all he could afford, but as she began to pull the ink from its shelf, Ukon suddenly hesitated. She glanced over her shoulder to make sure he could not see, and that no other customers had entered the shop. Then she swiftly replaced the inexpensive sumi stick with a chrysanthemum-shaped block of the most expensive ink her stepfather sold, scented with geranium leaves, and tinted a deep vermillion. She wrapped it in a second sheet of rice paper, so that the poet would not see its value and refuse it. Then she hurried back to the front of the shop.

“Here,” she said, bowing as she handed it to him.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Tails of Wonder and Imagination»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Tails of Wonder and Imagination» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Tails of Wonder and Imagination» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.