All things considered, we escaped rather less scathed than we might have been. A few men had been injured by falling debris and the recoil of snapped ropes, but none of the rest suffered more than scrapes. The burst stay was a serious concern, but our mast had not been broken, nor our hull too badly ruptured. We could afford to stay for a time and enjoy the fruits of our victory.

I could also release my pent-up feelings by chastising my son. Fixed as I was upon the battle against the serpent, I did not realize until afterward that Jake had not gone below with Abby as instructed. He had instead climbed the rigging up to the “top”—the platform where the lower section of the mast met the one above. He had taken with him a knife concealed inside his shirt, which he intended to use against the serpent by diving heroically on it from above. Fortunately for both his safety and my own sanity, common sense had prevented him from following through with this plan when he saw the bloody reality below him.

He was not as much daunted by this as I should have liked, though, nor did my reprimand leave much more of a mark. Mine was not the only tongue-lashing he received, though—Abby had already delivered one, as did the sailors in the top, several of the ship’s officers, Aekinitos himself, and Tom—and in the aggregate, they did have the effect of making him promise to be more obedient in the future.

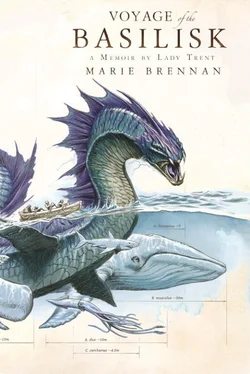

In the meanwhile, we had other tasks to which we must attend. The crew lowered the ship’s boats and used them to tow the beast back to our side, as they do with whales. We had to work quickly; already the carcass was drawing attention. Gulls flapped down to consider it, but disdained the meat after a few pecks; as with terrestrial dragons, the flesh of a sea-serpent is rather foul, owing to the chemical composition of the blood. There are scavengers in the sea, however, who do not mind its taste, and many of these came to investigate as we conducted our studies.

This at least was familiar work, although I had never before carried it out while straddling the carcass with my feet turning to ice in the sea. (I was, of course, wearing trousers, and had been since we left Sennsmouth.) I had to sit atop a piece of tough sailcloth, for the edges of the scales are viciously sharp; their serration had contributed to the destruction of the mainstay. Tom and his two allies had suffered numerous cuts, though that did not prevent him from joining me in the dissection once bandaged.

Those scales were the first focus of our interest. We had studied a few specimens donated to museums, for they are sometimes kept as items of curiosity by the sailors who kill the beasts. Without detailed information on their collection, however, those scales told us little. We hoped that by examining these closely and then comparing them against scales taken from a serpent in the tropics, we might establish more about the relation between the two. We also had the chemical equipment to try preserving a bit of bone, and extracted a vertebra for the purpose.

Then it was the basics, as we had practiced them before: we took a variety of measurements, and then Tom (whose tolerance for the cold water was much greater than my own) cut open the body to survey the internal organs. I meanwhile had the sailors remove the head and bring it on board, where I could study it in peace and relative warmth.

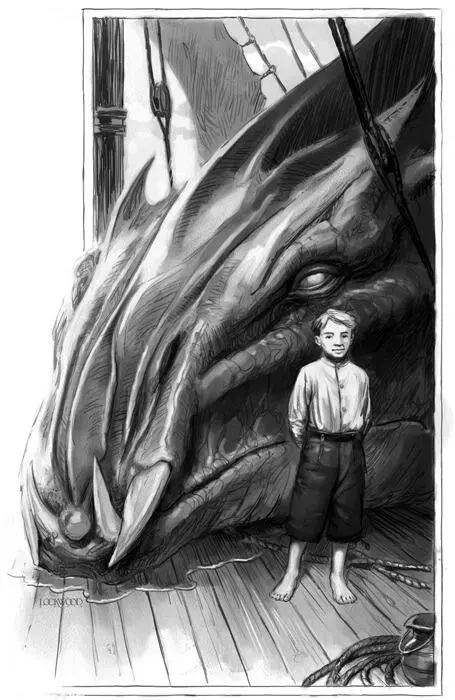

Jake knew I was a naturalist, of course. He had looked through my scholarly works, more for the plates that illustrated them than out of any deep interest in the text. Enough of the plates depicted anatomical drawings that he knew perfectly well what his mother did in her work. Knowing, however, was quite a different matter from seeing her in communion with a severed head.

He made an awed noise and laid his hand on one of its fangs. “Pray do not block my view,” I said, sketching rapidly. I wanted to finish quickly, so that I could deflesh the head and draw the skull. There appeared to be faint scars above its eyes, which suggested it might have once possessed the tendrils seen on its tropical kin.

“Is this bigger than the other dragons you’ve killed?” Jake asked.

“I have not killed any dragons myself,” I said. “Can you open its mouth? Or call one of the sailors to do it.”

Jake pried the head open, giving me a look when I warned him not to cut himself on the teeth. It is a look I think all children master at about his age—the one that insists the looker needs no warning while, by its very confidence, convincing the one looked at that the warning was very necessary indeed.

Open, the jaws could easily have swallowed my son. That gave me an idea. I said, “Stay where you are; I want to use you for scale.”

He mimed being eaten by the serpent, which would have been less unnerving had I not just been reminded of precisely how much danger I was placing him in by bringing him on this voyage. I had underestimated the hazards of hunting a sea-serpent. But I would not do so a second time; I vowed to put him ashore before we went after one in the tropics.

Jake soon tired of pretending to be a victim and so began mock-wrestling with the head, pretending to be its mighty slayer. “I’m going to kill one of these someday,” he proclaimed.

“I should prefer you didn’t,” I said, rather sharply. “I did this for science, but it having now been done, I hope it needn’t be done again. Only the fangs have any real value on the market, and those only as curiosities and raw material for carving; should an entire animal die, just so we might take four of its teeth? I almost feel sorry for it. At the end, it was trying to swim away. It only wanted to live.”

“She,” Tom said, climbing over the railing. He was dripping with bloody water. “No eggs in her abdomen, but the ovipositor marks her very clearly as female. I wonder where they lay them?”

My chastisement had made little mark on my son, but Tom’s revelation silenced him. Much later, he admitted to me that the pronoun was what struck him so forcefully: the pronoun, and the possibility of eggs. With those two words, the sea-serpent changed from a terrible beast to a simple animal, not entirely different from the broken-winged sparrow we had once nursed back to health together. A dangerous beast, true, and one that could have sent the Basilisk to the bottom of the ocean. But she had been alive, and had wanted to go on living; now she was dead, and any progeny she might have borne with her. Jake was very quiet after that, and remained so for several days.

Tom set to work defleshing the skull, and talked with me while he did. “The lungs are much like those we’ve seen in other dragons—more avian in structure than mammalian.” I sighed, thinking of my debate with Miriam Farnswood. I feared I was likely to lose that particular argument. “The musculature around the stomach and oesophagus is interesting, too. I’ll have to look at one of the tropical serpents to compare, but I think the purpose is to allow the creature to suck in water very swiftly, without having to swallow, and then vomit it back up again.”

JAKE FOR SCALE

“The jet of water,” I said, excited. “Yes, we’ll have to compare. If they do not migrate, perhaps their life cycle leads them further north as they age? A creature this large might have a difficult time keeping itself cool in tropical waters. That would explain why those in the north are generally larger, if their growth continues throughout their lives.”

We debated this point until the skull was clear of the bulk of its flesh. As I began sketching again, he asked me, “What do you think? Taxonomically.”

Читать дальше