We pounded across the sand toward that distant craft, tipped askew on the beach high above the breaking surf. Lieutenant Handeson took quick stock of the machinery and then all but threw two containers at me. “Quick! Fill those. Salt water is not the best, but—” I did not hear the end of his sentence, for Miriam had taken one of the containers, and we were already moving toward the sea.

While the two of us worked, the lieutenant and Suhail banged about the caeliger, cursing steadily. It seemed that something had broken, and must be wedged. “A branch!” Suhail shouted as we returned with water. “About this long—no thicker than my thumb—”

The beach was a bad place to look for branches; every tree in the vicinity was a palm. But Miriam and I ran up the slope and began rooting around in the fallen leaves, trying to find one whose stem was of a suitable size. In the middle distance, the knot of men was still deep in their scuffle around the huts. Someone had begun running toward us—a Keongan, by his size—but the engine of the caeliger was going; as soon as we found a wedge, we might take off and leave him behind. My hand closed on one at last, and I sprinted for the caeliger, calling for the princess to follow me.

From behind me, I heard a cry.

The messengers had gone for reinforcements; now the reinforcements had arrived. Two had come out of the trees, and they must have overcome their reluctance to lay hands on royalty, for they had Miriam in their grasp. I stopped dead in the sand, palm leaf clutched in my hand. I could not possibly free her from them, and if Suhail and the lieutenant came to my aid, the Keongan running toward us would stop the caeliger from taking off.

“Go!” Princess Miriam called, her voice more steady than I would have believed possible. Steady, and commanding. “Go! Find the admiral, and tell him where I am!”

To this day, I do not know if it was obedience or cowardice that turned my feet toward the caeliger. Suhail helped me over the edge; I tumbled to the floor, and a moment later that floor swayed beneath me as we left the beach behind.

Over the sea—Something in the gondola—Sails on the horizon—We flee—More sails—The wishes of the senior envoy—The Battle of Keonga

“She expected that to happen,” I said dully, staring up at the web of ropes that held the caeliger’s balloon. “She did not think she would get away with us.”

“I think it would be better to say, she planned for the possibility.” Suhail took the palm leaf from me, stripped it, and jammed it in among the recalcitrant machinery.

Lieutenant Handeson helped me to my feet. “She gave the orders ages ago, not long after we were taken. If anybody had a chance to escape, they should go. The Keongans won’t hurt her, and this way, we can send a rescue.”

Whereas if she came with us, they would move heaven and earth to retrieve her. I wondered suddenly if she had ever intended to get on board the caeliger. It would fly farther and faster with only three passengers—and if we were lost at sea, she would not be lost with us. No, I thought, not that last; she had shown no fear of drowning. But our chances were indeed better without her, even if Hannah and Captain Emery would have preferred to have her away from the Keongans at once.

Of course, any rescue would depend upon our speed. The Yelangese did not yet know that the missing princess was on Lahana, but no doubt they would wonder at the failure of their caeliger to return. Furthermore, the Keongans must assume that we would reach other territory and pass word along to our people. They would move Miriam, and soon.

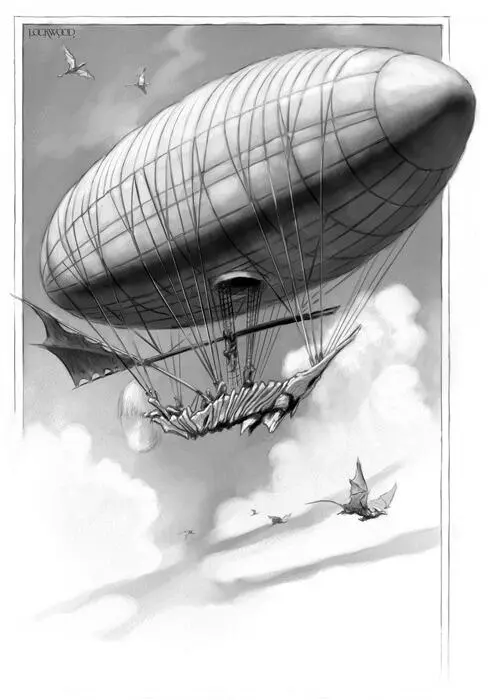

THE CAELIGER

I rose to my feet, moving carefully in the gondola. Dragonbone might be highly resistant to impact, but its light weight made the whole structure feel alarmingly flimsy. “What can I do to help?”

The answer was, very little. Between the two of them, Suhail and Lieutenant Handeson had sorted out the controls; the caeliger did not need three people to operate it. “Ordinarily I would say that flying at night is very hazardous,” the lieutenant said dryly. “But there is nothing out here for us to hit except the sea, and perhaps the occasional gull. So long as we keep a reasonable altitude, we should be fine. You should get some rest, Mrs.…” He trailed off, plainly realizing he had no idea who I was and why I had been included in the escape group.

“Camherst,” I said. We had a brief discussion of our plans; they amounted to “fly toward Kapa Hoa and hope we do not crash before we get there,” which did not leave much to discuss. Then I attempted to bed down, for I was indeed very tired.

There was a straw mat in one end of the gondola that I thought was intended as a place for crewmen to catch naps. When I settled into it, however, I found something else occupying the corner: the petrified egg from Rahuahane. Suhail had untied it from his body while we flew across to Lahana, and it had been overlooked in the crash.

I angled myself to hide the egg from Handeson’s eyes. This, too, was a secret, and one I could yet protect. If the Scirling navy learned there was an enormous cache of firestone on Rahuahane, the princess would not be the only thing they brought home from Keonga. I did not want the island raided for its treasure, and especially not before it could be properly studied.

Fortunately Handeson was busy with Suhail. They seemed quite impressed with the engine, which was, I gathered, a substantial improvement in smallness over the ones to which Handeson was accustomed. I wondered if that, too, had dragonbone components in it. (I later discovered that it did.) I tucked the egg into a coil of rope and then lay before it, hoping I could smuggle it off the caeliger without anyone else seeing. It did not look like firestone—the outer shell was dull rock—but I did not want it to attract any curiosity.

My thoughts would not permit me to rest. It was all too much, and too rapid; our discoveries on Rahuahane had been knocked clean out of my head by the encounter with the princess, let alone my breathless experience riding the sea-serpent. I wanted a moment somewhere quiet to ponder what I had seen, and paper on which to sketch it before the details slipped from my memory. But the gondola of the world’s first truly effective caeliger was not the place for such things, and our flight to obtain a rescue for the king’s niece was not the moment. I lay in the darkness, looking at Suhail’s profile against the brilliant background of the stars, listening to him murmur belated prayers in Akhian. I could not remember the last time I had prayed. I hoped Tom, Jake, and Abby were not too worried for me. Had anyone told them we had been found on Lahana?

And so the hours passed, until dawn came, and with it, sails on the horizon.

* * *

I had risen as soon as the light began to grow, having slept only in the most fitful snatches. Suhail had not slept at all, and looked as drawn and weary as I had ever seen him. He and the lieutenant were growing concerned about fuel; the wind was not entirely cooperating in our efforts to reach Kapa Hoa, and their best guess at reading the Yelangese navigational instruments said we were at risk of falling short. It was a pity, I reflected, that no one had thought to make the gondola watertight, for dragonbone floats quite well. Cut away the balloon, and we might have had ourselves a perfectly serviceable canoe—albeit one without a sail or paddles.

Because they were occupied with the caeliger’s machinery, I was the one who first spotted the sails. “Come look,” I said, breaking into their low-voiced discussion. “Are those not ships in the distance?”

Читать дальше