“Finally waiting on me,” he tried to say, but his voice was thready and cracked. He stopped to cough.

Mrs. Pennyworth bent down and kissed his forehead gently. “Now then,” she said, and he had the feeling she was addressing Casey, “ye see what has to happen to get him to not talk so much.”

Casey laughed, reaching to squeeze his arm. “I’m going to tell Tom you’re awake. We’ll give you two a few minutes.”

Sam turned his eyes back to Mrs. Pennyworth to see that she was picking up a glass of water with a straw. That sounded like the best idea in the world, and he let her put the straw in his mouth. He pulled the water in with strong gulps and coughed again.

She put the glass back and he reached up to wipe the tears from her face. “Hey,” he said, his voice a little clearer this time, “it sure is good to see you.” He didn’t know what his injuries were, but he sat up, ignoring the pain, and took her into his arms, holding her while she cried.

“I’ve never been so scared in all my life, Sam Altair,” she told him, voice muffled in his chest. “We didn’t know where ye were and then the hospital called…” She raised her head to look at him, touching his face. “But ye’ll be all right. That’s what the doctor says and I believe him. We’ll bring ye home and I’ll take care of ye.”

He smiled at her. “I can’t think of anything I’d enjoy more,” he said, then kissed her tenderly.

~~~

“You were in a deserted farmhouse outside of town,” Tom told him later that day, after Mrs. Pennyworth had returned home to pick up a few personal items for Sam. Casey sat in a chair next to Tom, legs pulled up against her as she rested her chin on her knees and gazed at Sam. “A passing farmer on his way home from the pub saw the flames. He was sober enough to pull you out of harm’s way and get help to put out the fire. They brought you to the hospital here, but you were unconscious for an entire day. We looked everywhere for you, but didn’t check with this hospital.” He leaned forward and whispered, “You’ll have noticed it’s a Catholic one” his eyes indicating the crucifix on the wall. Sam grimaced. He’d noticed. The nurses were nuns.

Tom leaned back. “Anyway, you came to enough to give them your name and have them call us, but it’s been another day while you’ve been drifting in and out of consciousness. You’re red as a lobster and blistered along your back. Your legs are black and blue and you’ve been throwing up like there’s no tomorrow. You’re lucky to have missed most of it. And that, sir, is all we know.” His eyebrows went up. “We’re hoping you can fill us in.”

Sam did, to the best of his ability, enduring their shocked interruptions and increasing horror.

Tom finally broke in. “You’ll have to talk to the police.”

Sam nodded, but looked uncertain. “What about Riley’s alibi? He’s right, even I thought he was out of town.”

“Well he wasn’t, was he?” Casey asked rhetorically. “Even if he left, he came back and then left again. Someone had to see him. Or maybe find out when he checked into his hotel.” She bounced her chin on her knees as she thought. “Is it too early for fingerprints?”

“I’m afraid so,” Sam told her.

Tom shook his head. “Not our problem. Talk to the police and let them handle it. They’ll take it from there.”

~~~

Since Riley’s conference was in Paris, the Belfast police could not do much to question him. They could not find anyone in town who had seen him on the day Sam was attacked. The university said that Riley had planned on staying in Paris for a few months, so they bided their time. Sam went home and settled down to recover from his ordeal. This was not as easy as he would have thought.

“Guess I’m too old for this sort of thing,” he joked to Casey as she brought him lunch a couple of days after he got home. He had tried to eat with them in the dining room, but his legs weren’t working well enough and he was just too tired. She positioned his tray and sat on the edge of the bed, smiling at him.

“You probably are,” she teased him. “Too old for what, exactly?”

He sighed. “You just wait, dear. One day, you’ll look back and realize that you used to bounce right back after injuries or illnesses. And you’ll wonder why you don’t bounce like that anymore.”

He took a moment to look her over while she laughed. When they’d first met, she’d been practically a child, smart, but light-hearted and hopeful, despite the circumstances. They’d only been here five years, but she had matured far in excess of that time. She still looked like a child. She could pass for eighteen rather than the twenty-five years she was. Except, there was a seriousness that made one pause and re-evaluate her age. Was it due to motherhood? Responsibility? The strain of fear that she carried within her, for all of them?

He sipped his soup and tried to banish morbid thoughts. Casey was fine. The public support she’d received since Tom’s letter was published had heartened her considerably. She was working, unofficially, with the Horticultural Society again, and was a popular figure at ladies’ teas. Where, she often said, they usually managed to solve the world’s crises before the pudding. Quite satisfactorily, too.

May 1911

The early mail on the second Tuesday in May brought a note from Casey’s sister-in-law, Jessie. The letter’s greeting made Casey’s heart squeeze in fear, but as she read on, laughter forced her to a chair in the parlor.

My Dearest Sister, the note began, John and I wish to extend our heartfelt condolences for whatever fate has befallen your husband. It has come to our attention (so we have acknowledged to each other), that the dear Fellow perhaps fell into the Lagan one day. Is it possible Uncle Willie neglected to inform you?

Well, we want you to know your family is ever full of love for you. As such, John and I request the honor of your presence at Maxwell Court for dinner, this Friday night. If, by some joyful miracle, you find our Tommy before then, by all means, bring him along. We shall expect you no later than seven o’clock, although I extend my personal wish to see your arrival even earlier than that.

In deepest love, Mrs. John M. Andrews

As it happened, Casey did not see Tom that night, but she left the note in his dressing room, where he would find it. The next morning it was on his pillow, with his scribbled note promising to be home early on Friday.

Wednesday night, as Casey sat in bed reading, the bedroom door silently opened and her husband crept into their bedroom. When he saw that Casey was still awake, he sighed, and continued the removal of clothes that he’d begun on the way up the stairs.

Casey watched him place coat and cravat on the dresser, and slip his suspenders off his shoulders. When he sat on the divan to remove his shoes, she closed her book and joined him, gazing at his face.

He smiled at her, but the smile did not quite erase the wrinkles of exhaustion at the corners of his eyes. “I’m pretty sure I still live here,” he said, his tone lightly questioning. “I did sleep in that bed for a few hours last night.”

“Did you?” she asked. “I must have missed it. In fact, I’ve been thinking of renting the space out, it’s been vacant so often.”

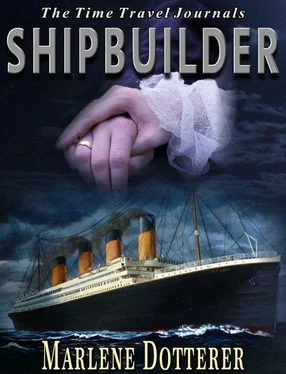

He laughed, but pulled her possessively against him with one arm, while the other hand buried itself in her hair, tilting her face up so he could look at her. “I miss you,” he said. “I can’t do anything about all the work, but I promise it won’t be like this forever. Once Olympic is turned over to White Star, and Titanic is launched…”

Читать дальше