I’d come home from Mexico, before the final collapse of the United States of North America, my last tour of duty, and we only managed to get back because we’d carried all the fuel for the return journey with us on the buses when we deployed. I was going through the motions of being a father to the boys — picking them up, swinging them round — but I was numb inside. Everyone in the military knew about PTSD by then, but somehow I figured my life had to have been threatened for me to have it. Jennifer and I made love that first night I came back, and I managed to hide what was going on inside my head, but after that I always begged off tired.

A year later, I took her out for a romantic dinner at one of the few restaurants still running in all the chaos and talked obsessively about the Mexican landscape, the cacti, the rodents and birds and insects. It was her birthday. She asked if I was all right, and I said I was. We drove home through a windstorm, paid the sitter, went upstairs. I kissed her, felt nothing, led her to bed and undressed her, felt nothing, which was, ironically enough, agony. I managed a fragile erection — my penis must have managed to have its own memory — and I entered Jennifer as quickly as I could before the whip cracked and horrible images stormed my mind.

My erection faded almost immediately. Jennifer tried to get me going. It was unbearable watching her from a thousand miles away. I put my hand on her head and whispered, stop. She rolled onto her back and looked at the ceiling, not breathing and then taking in the lightest wisp of air through her nose. I have never seen a human so alive yet so still.

What about me? she asked eventually. Then looked to the wall away from me. Is this ever going to end?

It’s not that I don’t want you. I actually suggested that they’d put too much potash or whatever in the bagged meals, and that maybe it would wear off. I put my arms around her, pulled her against me, and tried to console her, but it was like holding a giant bagged meal. She stuck with me for another year.

Stop, I ordered myself. Starlight from the window revealed the faint mass of the furniture in my bedroom in front of me. No reminiscing. A sudden snore-gasp came from Leo in the living room. I rolled onto my back and stared at the ceiling, taking in the lightest wisp of air through my nose.

In the morning, Leo groaned himself awake from the floor as I made tea. He seemed to expect me to serve his tea to him, which I did. When I last saw Leo, his business was starting to tank but he was still wealthy. Our mother’s funeral. Funeral is not the right word. The state was collapsing around us and formal annexation had done nothing to slow it. Hers was one of the last cremations. We intended to scatter her ashes at the cabin with Dad’s, but we couldn’t get the gas to make the trip north.

Nice apartment, he said, leaning on an elbow and looking around.

Don’t get any ideas.

You’ve taken neat to a whole new fucking level.

As you have slob.

He took a sip of his tea. Why did you come to Seattle anyway?

I brought the boys here after Jennifer died. We all needed a change of scene, and I thought Mom’s relatives could help with the boys while I looked for work.

You never called. You never wrote. He mimicked a complaining mother.

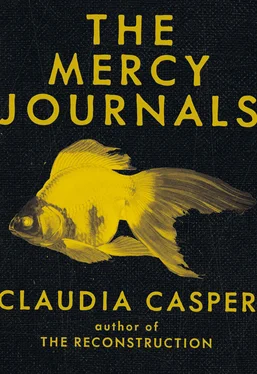

Never did. I got out the fish food. Never called the rellies either. I fed the fish.

I didn’t want to give him an opening, but I threw caution to the wind and asked what had happened to him since I last saw him.

Leo had always lived faster than anyone I knew. In grade six he sold fireworks; in high school he sold dope. He invested his earnings in stocks before he finished grade twelve. At university, while barely scraping through a degree in accountancy, he put together a stock deal that made millions. He moved to Seattle and invested in real estate. By age twenty, he had a yellow Corvette and partied hard six nights out of seven. A woman was sexually assaulted at a party at his place, but no charges were laid. Even when we knew for sure what was coming with climate change, even when everyone did, he was of the school that still wanted to take the planet out for one last, hard spin before trying to fix it. He was a let’s-have-fun-and-go-out-in-a-wild-beautiful-explosion kind of guy. His philosophy distilled down to, Nothing lasts forever.

And yet he always knew to the dollar bill what his net worth was and to the minute what time it was. He knew the exact number of kilometres his Corvette had logged, how much money friends owed him, how far he’d jogged in the past week, how many calories he’d eaten that day.

Daytime, he lived in a rapid-fire world of numbers, nighttime, in a euphoric, somewhat paranoid, substance-induced whirlwind. I didn’t see much of him after he moved to Seattle and Jennifer and I got married. He’d tried to get us to invest in a deal he was putting together, and tried to get our parents to as well, said we’d make a lot of money, and when we said no, he amped up the pressure. He went behind my back and tried to get Jennifer on board. When I confronted him he weaselled out, saying, I was only trying to help. If we had invested, we would have lost our shirts. Leo would probably have bailed us out but then we would have been beholden. I did not want to be beholden. My mother told me that a man had come looking for Leo and asked her how Leo made his money. Shortly after that Leo met and married Evie, an Australian working at a Tokyo chat bar. He got a job in a multinational life insurance company developing actuarial models for insurance against catastrophic weather events. He copyrighted his work and started his own business. Within five years, he was able to reveal that he was very, very rich. Evie and he had two girls as well as her son Griffin from a previous relationship.

Leo was unlucky in his parents. Our father, who adored the quasi-communal life of the army, might have accepted Leo’s wealth if he’d kept it hidden, but he didn’t know how to love a son who flaunted it, and our mother the high school English teacher was a socialist at heart. Leo was not someone I would have ever known if he wasn’t my brother, but I always felt connected.

He put his empty teacup on the floor, sat up, wrapped the blanket around his shoulders, and leaned against the wall. He spoke loud enough I could hear him over the noise of stirring the porridge I was making for our breakfast.

I managed to take out enough cash for Evie and me and the girls before the shit really started hitting the fucking fan. Buried it in a safe in the garden. We moved our beds into the kitchen and only heated that room. I had no work to go to, so I hung around the house all day driving Evie nuts. She got me digging up the lawn so she could put in some vegetables. She made me teach the girls how to read and do math. One day she told me to take some cash and see if I could buy some live chickens. I ended up walking way too far — I was blown away by the changes in the city, you know what it was like — I just kept walking and didn’t get back that night. I slept in a garden shed somewhere, woke up hungry, and ate some wormy apples. I went around knocking on the doors of houses where I smelled chickenshit, but no one wanted to trade the birds for cash. I slept out a second night and before dawn stole three chicks from one of the houses I’d visited.

I got depressed and just sat around watching Evie and the girls do all the work. She started giving me less and less food when she divvied up the dinner. I started to wander the city and sleep out more often, until finally I never went back.

The car you ticketed was stolen. I wanted to come and find you. I want to go to the cabin together. I’ve come to the end of myself.

I put in supplies for Jennifer, me, and the kids. Maybe they’re still there.

Читать дальше