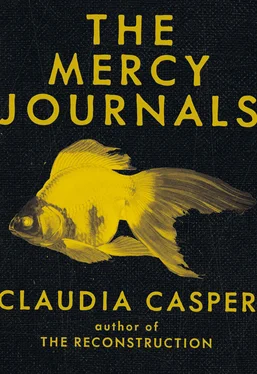

I went back to the kitchen for a soup ladle. Ruby was crouching in front of the shelf under the windows, looking through my micro library. Her jacket had fallen open. She wore a slip of sky blue silk — an arresting garment in these times. Its shimmer reminded me of the fish’s scales.

Just be a minute, I said, and disappeared back into the bathroom where I spooned the fish out of the toilet bowl back into the glass bowl and, for lack of any better place, hid it under my bed. I came back out and put the kettle on, closed the window, put the soup ladle in a pot to sanitize later, plugged the heater into my battery, set it in front of her, and asked if she was hungry. Before she answered I went to the coolbox, opened the door and announced, egg, sausage, and toast on the menu tonight.

She was back in the armchair, feet up on the ottoman, immersed in a book she’d chosen from the shelf. That blue silk clung to her. Starved, she said. Are you a decent cook? You don’t mind if I read while you work?

I can find my way around a frying pan. Read. More peace for the chef.

I was glad of the chance to get used to her presence without having to talk. I lay the sausages in the frying pan with a sizzle and stared out the window while they cooked, then broke the eggs into the pan and watched the tide of white move from the edges to the vortex.

She had ravaged me the last time and there was a predatory aspect to her now, like our family cat who used to pretend to sleep in the backyard while birds hopped closer.

I forked the sausages onto two plates, and the egg and toast, and called madam to dinner. I had one hand on the back of a kitchen chair while the other hung by my side, fluttering, as though I were playing alternating notes on a piano with my thumb and baby finger. She looked at that hand and lay the book down.

We sat at the table watching the goldfish while we ate. I berated myself for offering her dinner. It was much more awkward than just having sex. At least she was hungry. She ate voraciously.

Do you come from a large family? I inquired.

No. She took another bite and asked with her mouth full, Why?

Usually people who eat that fast had to compete for seconds.

No, I was an only child. I guess I just like to get to my pleasures fast.

I choked and laughed at the same time.

It was then I asked about her, where she grew up, that kind of thing. She gave me the thin version. A résumé.

I’m from Bellingham, former Washington State. Only child, older parents, both dead. Before the die-off I was a custom’s officer at the Peace Arch/Blaine border crossing. I did that for seven years. It got tough when people started trying to move north and the Canadians made us turn everyone back. The job got a lot better after annexation and all we had to do was direct people to the nearest resources. When OneWorld came into play I could’ve switched to doing city borders, but a lot of folks wanted that gig and I was done. I travelled for a couple of years, then I started performing. I sing and dance now to cover my rations and such. Though I could use a larger food ration.

It wasn’t hard to notice what was not being said. I travelled for a couple of years. What that would have meant for a lone woman in the early days of OneWorld. And then the next thirteen years— I sing and dance to cover my rations. I sensed a fellow loner marching with oblivion’s band, yet she seemed also to be facing forward, taking risks the way I used to. I admired her. She finished eating and lay her fork and knife neatly across the centre of her plate, pushed her chair out from the table, and tilted it back on two legs.

I looked up. The widest point of her face was just below where her eyes were. Her brows were dark and defined.

The last time someone looked at me, Allen Quincy, the way she did, was … never. I felt like a package being opened with an exacto knife.

She took my hand and led me to my own bedroom. She undressed me and then undressed herself. Her eyes were filled with light. She pulled me down to my bed and helped take off my prosthesis and put her lips to my stump and kissed it. Every nuance of movement between us seemed to spark another nuance. The feeling of skin, naked skin, was like waking up from a dream.

Next morning I woke up first. She was still in the bed beside me. It was my day off, it was Sunday, we could go to a teahouse, I could treat her to something. I was thinking maybe I could pull this off, this romance thing. I felt fine.

Usually I would have caught up on the news, maybe doubled up on my daily calisthenics, washed the laundry and hung it out if it wasn’t raining. I would’ve spent the afternoon at the library, come home, made dinner, and gone to bed.

Instead I doubled up on the porridge and tea and served madam in bed. She was strong, wiry, and hungry — a perfect combination of satiation and desire. A deep burn ignited in me, holding her that morning.

We stepped out together. The wind was up, the temperature suddenly warmer, warm for winter, even now, and the sky was brown. We could taste the dust from the Great Plains Desert a thousand kilometres to the east. Fine sand piled up in small drifts. We bent over to avoid the sting on our faces, held our coats closed, and pushed forward toward a new establishment announced in the news banners. We stopped under the viaduct for relief from the dust and wind. Our clothes and hair were covered. I blew sand out of Ruby’s eyelashes and she did the same for me.

I pointed out the putty-coloured man. She smiled and ran over to another painting of a window frame with fish swimming through it, placed one hand as though on the ledge, and turned and faced the fish so they seemed to be about to swim around her.

I can’t believe it, I said. I’m standing here with Mary Poppins in a sidewalk chalk drawing.

She pirouetted over to the giant, so that the large figure looked down at her with one eye and up at her with the other one.

Who’s Mary Poppins? This is excellent down here, Quincy. This one’s like Humpty Dumpty, but he’s not sure he wants to get back up on that wall. Who’s painting them? Where do they get the paint?

We walked back out into the driving airborne desert and continued forward. When we passed the old post office, we saw there was some kind of new indoor market happening. Plastic sheeting was tacked up over the broken windows near the ceiling, and it snapped and cracked like a rodeo whip in the wind. We went inside and wandered down the aisles, Hump and Stump and Twinkletoes, and looked at all the stalls where people sold or traded clothes, crockery, kitchen ware, home-brewed beer, baked goods, dried herbs, teas, home gadgetry, wood-working.

Ruby started to get excited. Flowers! Scones! She pulled me over to a stall. Look at this dress! I could create a piece around this. She smelled the armpits and crinkled her face. I don’t own enough perfume to cover that. She turned it inside out looking for a label. McQueen, she whispered to herself. How much? The woman in the stall turned around and looked Ruby up and down. She was missing two teeth. A mole near the corner of her mouth had sprouted several long hairs. She touched the hem of the garment lightly, gently rubbing the fabric between her thumb and forefinger, a slight tremor revealing itself when her hand stilled.

A movie star wore that exact same dress. One of the exotics. Was it Tilda Swinton?

Is it washable?

I don’t know. You can have it. A gift. The woman looked at me and winked. The only clothes I could imagine getting excited about when it came to Ruby was no clothes, but I was glad she was happy.

Ruby’s manner, usually so direct and self-possessed, had changed. A girlish side had surfaced. It was sweet but overdone and strained — like a daughter trying too hard to charm her father, not manipulatively but because she loves him and doesn’t know how else to connect. It surprised and touched me. As we walked together she began to dash about, exclaiming over everything and returning, eyes sparkling, putting her hands on my sleeve. I began to feel like a crab with a kitten.

Читать дальше