Where’d you meet a woman like that? he asked.

I don’t want to talk about it.

It’s not hard to see why you’d want to keep her all to yourself.

I remained silent.

Allen, give me some money for booze. Don’t worry, I’ll fuck off soon, but I have to have a drink tonight.

I bought him a half-litre of rye on the way to the dining hall. During dinner we asked about each other’s families to fill in the time. Leo said he used to walk by his old house and listen for their voices, but when the garden had been silent for a while, he stopped going by. He hadn’t had the courage to look inside.

It dawned on me to feel guilty that I never tried to contact my nieces. Luke and Sam used to bug me to visit their cousins, then they stopped. Leo and I forked our lasagne in. It had been a kind of madness not to think about my nieces during such dangerous times. I saw those two little girls with their pink ATVS and their big-screen TVS, their pom-poms and purses.

I got unnerved amid the clatter and talk in the cafeteria. Leo asked about Sam and Luke. He latched onto them as a subject. And I thought, why is he worrying about my sons instead of his daughters?

Allen, did you ever think they might have gone to the cabin? Did they ever talk to you about it?

Like I said, I was planning on taking the family there when things got really bad. The boys were young then, but they probably knew.

Allen. Let’s go. Let’s go up there. Let’s see if they’re there.

What about your daughters?

They might be there too.

I looked down at his empty plate and spoke slowly.

If the boys survived, they’re probably fine. If I start worrying about my sons, I will not be able to stay sane. My world is not big enough for that. They don’t need my shame. And I don’t need their forgiveness.

Leo was scanning the cafeteria.

Next morning, he was gone when I woke up.

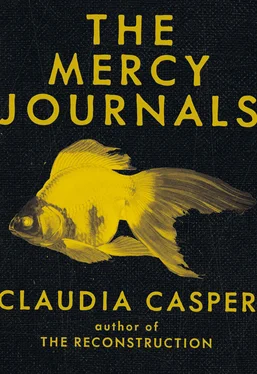

I checked if Leo had taken anything, then fed my fish as my tea was brewing and my porridge was setting. I watched them eat while I ate and drank. The males have longer, lighter-coloured feathery fins, while the females are rounder, bigger, and more efficient. Three of the fish darted with golden brilliance after the desiccated flakes drifting down past the plastic plants to the treasure chest with skull and crossbones that Luke gave me, but the fourth fish, a male, remained hovering near the bottom. I tapped the glass beside the fourth fish with my spoon. It spurted forward a bit, keeled over, then righted itself. They never get better. I tapped again and the sick fish shimmied slowly up to take a few unconvincing bites of a flake on the surface. One of the other fish swam over and jerked the flake away.

The sick fish sank back to the bottom. I finished my porridge. The sick fish depressed me. I washed my spoon and bowl and went to take another sip of tea when, out of the corner of my eye, I saw the sick goldfish give a sudden jerk. Two of the others had muscled into its corner behind the plastic plants and — I saw it — one of them swam up to the sick one and took a bite out of its fin. The sick fish jerked again and moved a couple of centimetres forward.

I sprang into action. I got more food and tried to fob the sons of bitches off with extra flakes. The new food distracted them for a minute or two, but then they closed in again. The sick one flapped its tail and moved a few centimetres as they approached.

My father used to say that only man is truly cruel because he has free will and is conscious of what he does. He said only man kills for fun. I wish he could see this. Try to imagine, I’d like to say to him, two men, stuffed to the gills, so to speak, so definitely not hungry, taking nibbles off a dying man — biting off an occasional toe or ear lobe, unaffected by his cries of pain. They wouldn’t be abnormal men, I’d explain to my father in a deadpan tone, just regular, everyday guys.

I filled a glass bowl with water, matching the temperature as best I could to the tank’s water, and got out my green fish net. I should’ve just flushed the sick one down the toilet. Without a miracle from the fish god — who never seems to dish out miracles — it was going to die. But because this tiny brainless flash of orange was my pet, I felt responsible for it.

I lowered the net into the tank. The sick fish scurried through the plants to the opposite side. The healthy ones also fled. Piscatory helter-skelter. After a couple of passes and a flick of my wrist, I caught the sick one and transferred it to the bowl. I picked out a sprig of fake greenery so the invalid would feel at home and sprinkled in a few flakes, in case it wanted to eat before going belly up.

Experience has taught me that there is no green net in life. I have only seen the opposite. When the other fish in your tank attack, you need your own army to survive, no matter how many representatives you have at the UN or OneWorld’s Regional Council.

I scrubbed the green net gently using dish detergent and a nail brush, rinsed it thoroughly with water from my rainwater bucket, dried it first with a towel, then by waving it in the air, and returned it to its place in the utensil drawer. By the time I pushed the drawer shut, the tremors had come on and I had to get to work.

I was tired that day. Leo’s visit had drained me, but when I handed my scanner back to Velma and hung up my uniform jacket, I got a surge. Ruby! I checked the time on my mobile, thought it must be about the same as the last two times I’d met her. I lounged against the stone wall like a man with nothing to do but wait for a woman. I picked out the sound of her heels from a distance and waited with a silly grin. I invited her for dinner.

I live in an old office building near the original railway yard. It was converted to apartments at the turn of the century. Its front entrance has been boarded shut and a small door fitted inside the old one to minimize heat loss. I unlocked the door and held it open for her. We still had just enough daylight to make our way up the three flights of stairs with me touching the wall and leading the way. I got my key out of my pocket and lifted it to the keyhole. The air in the hallway seemed suddenly sucked away and a shyness came over me, which I tried to hide. I unlocked the door to my apartment, switched on the light, and held the door open.

What a pauper’s gesture! Come in to my garden of earthly delight, my nest, lovingly built to attract a mate. I had never really seen my apartment until this moment. Other than the one coat hook, I had taken no steps to make it home. There were no curtains, no pictures, no vases or trinkets or photographs. The place was the civilian version of a barracks. I also smelled it for the first time, the heretofore invisible scent of self, like the smell of clothes brought out of storage — the musty skin oils that laundering never quite removes. The overall ambience would not be helped by the goldfish, now floating belly-up in the glass bowl beside the kitchen sink, luckily mostly hidden by a tall jar of oats.

Ruby ducked under my arm. Of course she’d already seen my apartment, but not formally, not by invitation, not with my conscious awareness. I followed her in, went directly to the living room window, and opened it. I invited her to sit in the stuffed chair, grabbed Leo’s bedding from the corner, took it into the bedroom, and shoved it in the closet. I had the thought of changing the locks; he was the kind of guy who would get a key copied. Then I picked up the glass bowl, holding it in front of me so my body blocked her sightline, and rushed it to the bathroom. I poured the contents into the toilet, briefly admired the beauty of my fish, and flushed, but the water pressure was too low to push even a raisin down the pipe.

Читать дальше