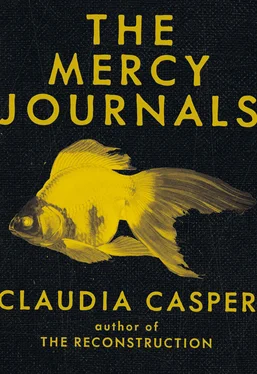

Claudia Casper

The Mercy Journals

To James Griffin, the love of my life

On October 15, 2072, two Moleskine journals were found wrapped in shredded plastic inside a yellow dry box in a clearing on the east coast of Vancouver Island near Desolation Sound. They were watermarked, mildewed, and ragged but legible, though the script was wildly erratic. Human remains of an adult male were unearthed nearby along with a shovel and a 9mm pistol. Also found with the human remains were those of a cougar. The journals are reproduced in their entirety here, with only minor copy-editing changes for ease of reading.

My name is Allen Levy Quincy. Age 58. Born May 6, 1989. Resident of Canton Number 3, formerly Seattle, Administrative Department of Cascadia.

This document, which may replace any will and testament I have made in the past, is the only intentional act of memory I have committed since the year 2029. I do not write because I am ill or because I leave much behind. I own a hot plate, three goldfish, my mobile, my Callebaut light, my Beretta M9, the furniture in this apartment, and a small library of eleven books.

I sit at my kitchenette island in this quasi-medieval, wired-by-ration, post nation-state world, my Beretta on my left, bottle of R & R whiskey on my right, speaking to the transcription program on my mobile.

I was sober for so long. Eighteen years. I was sober through what seems to have been the worst of the die-off. Three and a half to four billion people, dead of starvation, thirst, illness, and war, all because of a change in the weather. The military called it a “threat multiplier.”

You break it, you own it — the old shopkeeper’s rule. We broke our planet, so now we owned it, but the manual was only half written and way too complicated for anyone to understand. The winds, the floods, the droughts, the fires, the rising oceans, food shortages, new viruses, tanking economies, shrinking resources, wars, genocide — each problem spawned a hundred new ones. We finally managed to get an international agreement with stringent carbon emissions rules and a coordinated plan to implement carbon capture technologies, but right from the beginning the technologies either weren’t effective enough or caused new problems, each of which led to a network of others. Within a year, the signatories to the agreement, already under intense economic and political pressure, were disputing who was following the rules, who wasn’t, and who had the ultimate authority to determine non-compliance and enforcement.

Despite disagreements, the international body made headway controlling the big things — coal generators, fossil fuel extraction, airplane emissions, reforestation, ocean acidification — but the small things got away from them — plankton, bacteria, viruses, soil nutrients, minute bio-chemical processes in the food chain. Banks and insurance companies failed almost daily, countries went bankrupt, treaties and trade agreements broke down, refugees flooded borders, war and genocide increased. Violent conflict broke out inside borders, yet most military forces refused to kill civilians. Nation-states collapsed almost as fast as species became extinct. Eventually the international agreement on climate change collapsed completely, and the superpowers retreated behind their borders and bunkered down. The situation was way past ten fingers, eleven holes; it was the chaos that ensues after people miss three meals and realize there’s no promise of a meal in the future.

Our dominion was over.

A group of leaders — politicians, scientists, economists, religious and ethnic leaders, even artists — people with a vision, called a secret conference with the remaining heads of state and emerged with an emergency global government, agreed-upon emergency laws, and enforcement protocols. The new laws included a global one-child limit and a halt to all CO2 emissions. The provision of food and health care to as many people as possible was prioritized, along with militarily enforced peace, severe power rations, and further development of renewable energy. The agreement was for one year, but it’s been renewed every year for the past fifteen.

Why am I voicing all this? You already know it, I already know it, but I rehearse the events again and again, looking for what we could have done differently; there were so many things, so many ways we could have avoided most of the deaths, but really, were we ever going to act differently? I pour another drink. I drink it.

I was sober through most of that history. I stayed sober when my ex-wife died of a deadly new variant of the hantavirus that had spread north, and I stayed sober when I took care of my sons. Sober even though they acted like I was the volatile element in their lives and looked only at each other when I spoke to them. When I left for work and listened at the door, they finally became animated and relaxed enough to be afraid of everything else in the world crashing down on them. I tried to be tender with them, to lay my hand on their heads, put an arm around their shoulders, but they’d wince or stay perfectly still. I was sober through all that.

But now I’m drunk.

Last week I went out and got a mickey of whiskey from the bootleg. This week, a bottle a night is barely touching it, so I went down to the corner. It was still the corner. I’m not fussy, I told the guy, just get me out of my mind. He hunched deep in his coat, causing his demi-gray ponytail to fan out at the collar. He sucked mucus in and horked, a gesture communicating both his contempt and camaraderie for his customers. Whole ecosystems have vanished but …

Ambien, O.C.? I suggested. Triple C, anything. Walking away with four pills in my pocket, I passed a scattering of young women and men trying to get shelter in a loading bay from a wind that peppered us all hard with squally rain. They looked like they were waiting for a delivery. I felt sorry for them and hoped it wasn’t long in coming.

I don’t know what he sold me — something new: Mimosa. You’ll feel mellow as butter in ten minutes, he said, with no weirdness. I dropped by the bootleg and bought a couple of bottles just in case. Took a slug, wrapped a sweater round one of the bottles so they wouldn’t clank in my pack, and headed for home. I started to feel the relief of knowing I had something that would bring relief. A few blocks from my apartment I got dizzy, which happens periodically since my condition started. I managed to make it to a small park and lean against one of the scrawny trees the city planted to replace the ones that keeled over in the last windstorm. I lay my cheek up against its cool, wet bark and closed my eyes. I don’t know how long it took for my head to clear, ten minutes, two hours, but eventually I opened my eyes again. I was staring at the sparse grass at my feet. The earth between some of the blades began to move as pea-sized balls of dirt were pushed up from below. Then I glimpsed what was pushing the dirt — worms — purply-pink, the colour of cold lips.

They finished clearing out the entrances to their holes and popped out, eight of them, sticking up like baby fingers. They were a real demographic mix — from young to old, hermaphroditic to gendered, light pink to medium purple. They waved their stick arms in cheery exuberance and were almost endearing, if you can say that about worms. They smiled at me like they knew me, then glanced at each other in nervous excitement, and one of them counted off, A one, and a two, and a one, two, three … They broke into song, harmonizing like a barbershop octet, with fake British accents:

Читать дальше