“But of iron?” Frances asked.

“Oh yes, the very first rimes were made out of iron, you know.”

“And what of the five hundred years?”

“I think it’s considerate that he would wait five hundred years after you die to take another wife.”

“Yes, I suppose so, Oread.” But Frances wasn’t completely at ease with her family.

Henry always made a good living from his typewriter repair shop, or rather he made a good living from his parts stocks in the rooms behind. Other dealers and repairmen, not just of typewriters but of everything, came to him for parts. His prices were reasonable, and there was never a part that he didn’t have. A dealer would rattle off the catalog number of something for a tractor or a hay-baler or a dishwasher. “Just a minute,” Henry Funnyfingers would say, and he would plunge into his mysterious back rooms. He had a comical little song he would croon to himself as he went:

“Oh Kelmis, Oh Acmon, Oh Damnae all three,

Now this is the number, Oh make it for me!”

And in a second, with the last word of the song just out of his mouth, he’d be back with the required part still hot in his hand. He never missed. Parts of combines, parts of electric motors, parts for Fords, he could come up with all of them instantly with only a catalog number or the broken piece itself or even a vague description to go on. And he did repair typewriters quicker and better than anyone in town. He wasn’t rich, he was fearful of becoming rich; but he did well, and nobody in the Funnyfinger family wanted for anything.

When they were in the sixth grade, Oread had a boyfriend. He was a Syrian boy named Selim Elia. He was dark and he was handsome. He looked the veriest little bit as though he were made of iron; that was the main reason that Oread liked him. And he seemed to suspect entirely too much about the funnyfingers; she thought that was a reason that she’d better like him.

“When you grow up (Oh, Oread, will you ever grow up?) I’m going to marry you,” Selim said boldly.

“Of course I’ll grow up. Doesn’t everyone?” Oread said. “But you won’t be able to marry me.”

“Why not, little horned owl?”

“I don’t know. I just feel that we won’t be grown up at the same time.”

“Hurry up then, little iron-eyes, little basilisk-eyes,” Selim said. “I will marry you.”

They got along well. Selim was very protective of little Oread. They liked each other. What is wrong with people liking each other?

When in the eighth grade, Oread made a discovery about Sister Mary Dactyl, the art teacher for all the grades. Sister Mary D seemed to be very young. “But she can’t be that young,” Oread told Selim. “Some of the mythological things she draws, they’ve been gone a long time. She has to be old to have seen them.”

“Oh, she draws them from old stories and old descriptions,” Selim said, “or she just draws them out of her imagination.”

“A couple of them she didn’t draw out of her imagination,” Oread insisted. “She had to have seen them.” That, however, wasn’t the discovery.

Sister was drawing something very rapidly one day, and she forgot that someone with very rapid eyes might be watching her hands. Oread saw, and she waited around after class.

“You are a funnyfingers,” she said to Sister. “All your fingers are triple-jointed like mine. They can move fast as light like mine. I bet you can pick up iron parts out of the hot pots without getting burned.”

“Sure I can,” said Sister M.D.

“But are you a funnyfingers all the way?” Oread asked. “Papa says that, in the old language, our name Funnyfingers meant both funny-fingers and funny-toes. Are you?”

“Sure I am,” said the very young-looking Sister Mary Dactyl. She took off her shoes and stockings. Sisters didn’t do that very often in the classroom then. Now, of course they go everywhere barefooted and in nothing but a transparent short shift, but that wasn’t so when Oread Funnyfingers was still in the eighth grade.

Yes, Sister was a funny-toes also. She had the triple-jointed fast-as-vision toes. She could do more things with her toes than other people could do with their fingers.

“Did you have a little hill or mountain when you were young, I mean when you were a girl?” Oread asked her.

“Oh, yes, yes, I have it still, an interior mountain.”

“How old are you, sister who always looks so young and pretty?”

“Very old, Oread, very old.”

“ How old?”

“Ask me again in eight years, Oread, if you still want to know.”

“In eight years? Oh, all right, I will.”

High school went by, four years just like a day. Selim had made a big twisted hammered iron thing that said “Selim Loves Oread.” He suspected something very strongly about the iron. But he wasn’t a funny-fingers, so it took him three weeks instead of three seconds to make the thing. Many other things happened in those four years, but they were all happy things so there is no use mentioning them.

When they were in and almost through college (Oread still looked like a nine- or ten-year-old, and this was maddening) they were into some very intricate courses. Selim was a veritable genius, and Oread always knew in which pots the answers might be found, so the two of them qualified for the profound fields. It is good to have a piece of the deep raw knowledge as it births, it is good to see the future lifted out of the future pots.

“We have come to the point where we must invent a whole new system of concepts and symbols,” said the instructor of one powerful course one day. “Little girl, what are you doing in this room,” he added to Oread. “This is a college building and a college course.”

“I know it. We’ve been through this every day for a year,” she said.

“We are as much at a crossroads as was mankind when the concept of a crossroads was first invented,” the instructor continued. “If that concept (excluding choice pictured graphically with simple diverging lines) had not been invented, mankind would have remained at that situation, unchoosing and merely accepting. There are dozens of cases where mankind has remained in a particular situation for thousands of years for failure to invent a particular concept. I suspect that is the situation here; we have not moved in a certain area because we have not entertained the possibility of movement in that area. A whole new concept is needed, but I cannot even conceive what that concept should be.”

“Oh, I’ll make it for you tonight,” Oread said.

“Has that little girl wandered into the class again today?” the instructor asked with new irritation. “Oh yes, I remember now, you always come up with some sort of proof that you’re an enrolled member of the class and that you’re twenty-one years old. You’re not, though. You’re just a little girl with little-girl brains.”

“Oh, I know it,” Oread said sadly, “but I’ll still make the thing for you tonight.”

“Make what thing, little girl?”

“The new concept, and the symbol set that goes with it.”

“And just what does one make a concept out of?” that man asked her with near exasperation.

“I’ll make it mostly out of iron, I think,” Oread said. “I’ll use whatever is in the pots, but I guess it will be mostly iron.”

“Oh God help us!” the man cried out.

“Such a nice expression,” Oread told him, “and somebody had told me that you were an unbeliever.”

“Actually,” said the instructor, controlling himself and talking to the rest of the class and not to Oread Funnyfingers. “Actually, these things often appear simple in retrospect. So may this be if ever we are able to make it retro. The ABCs, the alphabet isn’t very hard, is it? Yes, Mr. Levkovitch, I know all about those hard letters after C. A little humor, it is said, is a tedious thing. But the alphabet was a hard thing when mankind stood at the foothills—”

Читать дальше

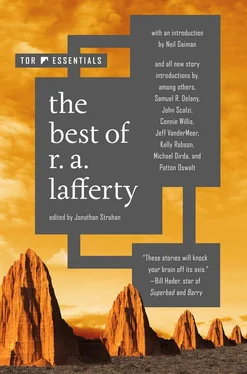

![Рафаэль Лафферти - Дни, полные любви и смерти. Лучшее [сборник litres]](/books/385123/rafael-lafferti-dni-polnye-lyubvi-i-smerti-luchshe-thumb.webp)

![Рафаэль Лафферти - Лучшее [Сборник фантастических рассказов]](/books/401500/rafael-lafferti-luchshee-sbornik-fantasticheskih-ra-thumb.webp)