Every decade or so, somebody with a passion for regularity takes over the administration of the Directory and Delineation of Planets, that massive cataloging operation, and makes a new survey of the anomalies. And there was not any way that such a survey could miss Thieving Bear Planet.

“It offers no threat to human life or activity, no danger to bodily health, and only slight danger to mental health,” the great John Chancel had written about it a century before this. “It has almost uniformly ideal climate, though it is not a place to generate sudden wealth. It is serene in environment and in ecological balance, and it is absolutely caressing in its natural beauty. But it does have a strange effect on some of its visitors. It forces them to write things that are untrue, as it is forcing me to do at this moment.” That was an odd thing to write in a ship’s log.

And, as one later old hand put it, “There is nothing to conquer here. It is a poorly endowed and counterproductive world. And everything goes wrong here. I will say this for it: things go wrong here in the most pleasant way possible. But they do go wrong.”

Now another expedition consisting of six explorers—George Mahoon (he was wrestler-big, and with a groping, grappling, leverage-seeking wrestler-mind); Elton Fad (he was long on information and short on personal incandescence); Benedict Crix-Crannon (buff and charming, and he knew all the jobs of the expedition); Luke Fronsa (he was a “comer,” as they said in the department, but wasn’t he a little bit overage in grade as a “comer” now?); Selma Last-Rose (what can you say after you say that somebody has everything?); Gladys Marclair (pleasant, capable, but she wasn’t a genius, and genius was really required for an explorer); and Dixie Late-Lark (sheer Spirit, she!)—had set down on Thieving Bear Planet. These were not the most experienced explorers in the Service, but they were among the newest and freshest. And they had already demonstrated that they were top people at clearing up anomalies.

“It’s a pleasant place, but not good for much,” George Mahoon said before they had been there ten minutes. “Why didn’t the earlier explorers simply say that it was ‘Only marginally or submarginally productive, indicated by fast scans to be poor in both radioactive and base metals and also in rare earths and fossil fuels, not recommended for development in the present century when so many better places are available,’ or some such thing as that? Why did they put so much stuttering gibberish in their reports? I’m going to like it here, though. It’s nice for a brief vacation.”

“Oh, I’m going to like it too,” Selma Last-Rose spoke in her curious rat-a-tat-tat voice. “There must be a puzzle here, and I like puzzles. And there’s a minor mystery in this ‘Plain of the Old Spaceships.’ I may as well solve that.”

They had landed in a clear place on the Plain of the Old Spaceships. Here there were remarkable full-scale drawings or schematics of old spaceships, twelve of them in two-thirds of a circle, from the earliest to the latest, going clockwise on the ground. What medium these schematics were done in was not certain, but the lush grass refrained from growing on the lines of them and so marked them off. The “drawings” showed the circle-spheres of the spaceships and their fore and aft bulges. They gave accurate indication of the interior bulkheads. This was really a life-sized museum of ships that lacked only substance and the dimension of height.

“I recall two passages in the log of the ship Sorcerer about this plain or meadow,” Elton Fad said. “The first of them stated, ‘Some of our party believe that the plain of the ships was actually done by the Thieving Bears in a historical marker sort of response, but I myself do not credit the little beasties with that much intelligence.’ And there was a later entry in another hand, ‘The Thieving Bears really did make those schematics-in-the-grass memorials of all the spaceships that had been here, but they didn’t do it in any way that we had imagined.’ But that latter log entry, like latter entries of several of the explorers, had been written in something other than ink.

“Well, I’ll imagine a few ways that the little buggers could have done it, and I’ll test it somehow. I’ll ask them how they did it. If the tittering little obscenities have any intelligence at all, I’ll find a way to ask them.”

The “tittering little obscenities,” the Thieving Bears, were not much like bears. They were more like large flying squirrels, and they did glide on the winds, apparently for sport. They were more like pack rats (the Neotoma cinerea of Earth) both in appearance and in their thieving ways, but larger. It was old John Chancel who had named the species “ Ursus furtificus, the Thieving Bears.” Oh, the explorers had their introduction to the thieving of the little animals within five minutes of planet-landing. The creatures came into the ship itself and got into places that should have been impossible to them. They stole Selma’s candy and Dixie’s snuff. They stole (by drinking it on the spot) George Mahoon’s “He-Man Scent—Cinnamon,” thirteen bottles of it, but they did not drink any of the other scents. They went wild over mustard, emptying whole containers of it and then wheezing in delicious agony from the effect. Elton Fad tried to drive them away with heavy sticks. They fastened onto the sticks while he swung them and ate them right up to his hands. They were funny, but they could become infuriating. They stole six of Dixie Late-Lark’s French horror story novels.

That wouldn’t be fatal to her. She had lots of them.

“They’re going to sample them,” Dixie said. (She herself looked a little bit like one of those Thieving Bears.) “They’ll be the test. If they do read them and appreciate them, it’ll prove that they’re intelligent creatures and have better reading tastes than my crewmates. That will be a start in analyzing them, something to put into the electronic notebooks.”

Could the Thieving Bears talk? That was not determined for sure within the first ten or even twenty minutes.

“Say ‘Good morning,’ fuzzy head,” Selma rattled at one of the creatures.

“Say good morning, fuzzy head,” it bear-barked back at her. Well, it had the right number of syllables, and the right rhythm and stress. And the bear-barks did resemble Selma’s rattling words. And whenever the bears answered one of the persons, it answered in that person’s own timbre. The bears began to imitate the people quickly, and there was never any doubt as to which person was being imitated.

The tittering that went with the imitations, though! Ooooh, that could become tiresome after a little while. “Tittering little obscenities,” yes.

Could the Thieving Bears read? ’Twould be known in a bit, maybe. The bears had gotten into those big lockers that were full of comic books and had stolen big bunches of them. These comic books from the Trader Planets were now collector’s items on Old Earth, and they generated quite a profit. The wonderful things should be collector’s items everywhere.

Some of the big Thieving Bears were “reading” those comic books to some of the little Thieving Bears, reading them in the Thieving Bears’ own barking talk. And some of the little bears would bark their excitement and incredulity at parts of the narration and would come and look at the pictures and the worded balloons themselves. And then there would be that damned tittering!

It was clear that the big bears believed that they were reading, and that the little bears believed they were understanding. But the wording in the comic book balloons was in the Gno-Pidgin dialect of the Trader Planets, and people from the Traders had never been to Thieving Bear Planet. It was almost too much to believe that “Sangster’s Syndrome Intuitive Translation” was being practiced by animals below the level of conceptual thinking. Then some of the little bears were clearly acting out episodes from the comic books (very subtle episodes, according to Benedict Crix-Crannon, who had total knowledge of the content of all the comic books from the lockers). Well, there was no easy explanation for that.

Читать дальше

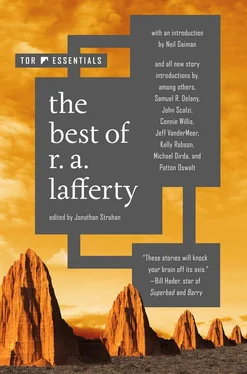

![Рафаэль Лафферти - Дни, полные любви и смерти. Лучшее [сборник litres]](/books/385123/rafael-lafferti-dni-polnye-lyubvi-i-smerti-luchshe-thumb.webp)

![Рафаэль Лафферти - Лучшее [Сборник фантастических рассказов]](/books/401500/rafael-lafferti-luchshee-sbornik-fantasticheskih-ra-thumb.webp)