Ah, it was not the same 3rd Street he had once visited before; almost the same but not exactly. An ounce of reassurance was intruded into the tons of alarm in his heavy head. But he was alive, he was well, he was still traveling west in the boundless City that is everywhere different.

“The City is varied and joyful and free,” William Morris said boldly, “and it is everywhere different.” Then he saw Kandy Kalosh and he literally staggered with the shock. Only it did not quite seem to be she.

“Is your name Kandy Kalosh?” he asked as quakingly as a one-legged kangaroo with the willies.

“The last thing I needed was a talkie,” she said. “Of course it isn’t. My name, which I have from my name-game ancestor, is Candy Calabash, not at all the same.”

Of course it wasn’t the same. Then why had he been so alarmed and disappointed?

“Will you travel westward with me, Candy?” he asked.

“I suppose so, a little way, if we don’t have to talk,” she said.

So William Morris and Candy Calabash began to traverse the City that was the world. They began (it was no more than coincidence) at a marker set in stone that bore the words “Beginning of Stencil 35,353,” and thereat William went into a sort of panic. But why should he? It was not the same stencil number at all. The World City might still be everywhere different.

But William began to run erratically. Candy stayed with him. She was not a readie or a talkie, but she was faithful to a companion for many blocks. The two young persons came ten blocks; they came a dozen.

They arrived at the 14th Street Water Ballet and watched the swimmers. It was almost, but not quite, the same as another 14th Street Water Ballet that William had seen once. They came to the algae-and-plankton quick-lunch place on 15th Street and to the Will of the World Exhibit Hall on 16th Street. Ah, a hopeful eye could still pick out little differences in the huge sameness. The World City had to be everywhere different.

They stopped at the Cliff-Dweller Complex on 17th Street. There was an artificial antelope there now. William didn’t remember it from the other time. There was hope, there was hope.

And soon William saw an older and somehow more erect man who wore an armband with the word “Monitor” on it. He was not the same man, but he had to be a close brother of another man that William had seen two days before.

“Does it all repeat itself again and again and again?” William asked this man in great anguish. “Are the sections of it the same over and over again?”

“Not quite,” the man said. “The grease marks on it are sometimes a little different.”

“My name is William Morris,” William began once more bravely.

“Oh, sure. A William Morris is the easiest type of all to spot,” the man said.

“You said—no, another man said that my name-game ancestor had to do with designing of another thing besides the Wood Beyond the World, ” William stammered. “What was it?”

“Wallpaper,” the man said. And William fell down in a frothy faint.

Oh, Candy didn’t leave him there. She was faithful. She took him up on her shoulders and plodded along with him, on past the West Side Show Square on 18th Street, past the Mingle-Mangle and the Pad Palace, where she (no, another girl very like her) had turned back before, on and on.

“It’s the same thing over and over and over again,” William whimpered as she toted him along.

“Be quiet, talkie,” she said, but she said it with some affection.

They came to the great Chopper House on 20th Street. Candy carried William in and dumped him on a block there.

“He’s become ancient,” Candy told an attendant. “Boy, how he’s become ancient!” It was more than she usually talked.

Then, as she was a fair-minded girl and as she had not worked any stint that day, she turned to and worked an hour in the Chopper House. (What they chopped up in the Chopper House was the ancients.) Why, there was William’s head coming down the line! Candy smiled at it. She chopped it up with loving care, much more care than she usually took.

She’d have said something memorable and kind if she’d been a talkie.

Introduction by Andrew Ferguson

Ask a few readers of Lafferty what they treasure him for, and you’ll get a lot of the same answers. He will make you laugh, uproariously. He will show you new possibilities inherent in language—not just in English, but many others as well. He will provide you a vantage point on this world (and other worlds, to boot) that flips you inside out, inverting everything you thought you knew about the workings of fiction.

What they won’t mention as often—partly because he doesn’t do it that much, and partly because it hurts so much when he does—is that he will break your heart wide open.

“Funnyfingers” is, at its most basic level, a tale of doomed love. It isn’t spoiling anything to say that in an introduction, either, because as he often does, Lafferty tells us what’s going to happen right from the start. Here it’s in an epigram alluding to Orpheus, something you don’t do unless a Eurydice is about to be lost. With admirable narrative economy, the main character immediately thereafter poses the central question that will lead to her romantic impasse—who, or what, am I?—and then the reader is given several valid answers: she is a somewhat exasperating and precocious little girl, and she is also a young Dactyl, a creature of myth, one of a number who gave humankind ironworking, arithmetic, and the alphabet and who (in their adult years) remain responsible for manufacturing letters and numbers and pieces for the entire world.

The story plays out from there, though the narrative beats and resolution are hardly formulaic. However, Lafferty is as usual concerned with much more than just the central relationship of his unhappy couple: he’s exploring humanity’s relationship with its stories, as well as his own particular relation as a channel for those myths. While Lafferty’s personal relationship experience was limited to what he could glean from others, he nonetheless understood that much of what we love about another is the stories we construct around them, myths that are deeply personal even as they partake of the universal. But when what you love is a story—or you yourself are a story—the deck is stacked against you from the start.

As the young lovers in “Funnyfingers” realize to their dismay, our stories will outlive us, and in particular they will outlive their own tellers. The result is a curious (if typically Laffertian) inversion of the Orpheus legend: it’s not the stories who must be left behind to the darkness, but us. When Oread Funnyfingers traipses through the mine, assembling iron dogs or iron boys or iron philosophies, it’s us she’s putting together. And when she disassembles them at the end of play, it’s us she puts back in the spare-part bins. And, in the end, though we too feel heartbreak at the conclusion of our all-too-brief parts, it is Oread and it is Pluto, the stories themselves, who will weep iron tears.

“—and Pluto, Lord of Hell, wept when Orpheus played to him that lovely phrase from Gluck—but these were iron tears.”

—H. Belloc,

On Tears of the Great

“Who am I?” Oread Funnyfingers asked her mother one day, “and, for that matter, what am I?”

“Why, you are our daughter,” the mother Frances Funnyfingers told her, “or have you been talking to someone?”

“Only to myself and to my uncles in the mountain.”

“Oh. Now first, dear, I want you to know that we love you very much. There was nothing casual about it. We chose you, and you are to us—”

Читать дальше

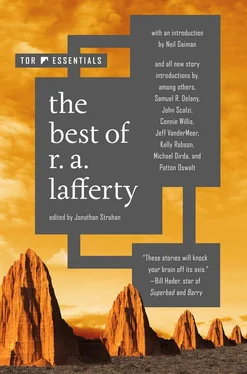

![Рафаэль Лафферти - Дни, полные любви и смерти. Лучшее [сборник litres]](/books/385123/rafael-lafferti-dni-polnye-lyubvi-i-smerti-luchshe-thumb.webp)

![Рафаэль Лафферти - Лучшее [Сборник фантастических рассказов]](/books/401500/rafael-lafferti-luchshee-sbornik-fantasticheskih-ra-thumb.webp)