“I chose the wrong one,” said old Charles Archer as they rode along through the textured country. “One can now see how grotesque was my choice, but I was young. In two years, the stock-selling company in which I had invested was out of business and my loss was total. So early and easy riches were denied me, but I developed an ironic hobby: keeping track of the stock of the enterprise in which I did not invest. The stock I could have bought for thirty-five thousand dollars would now make me worth nine million dollars.”

“Ugh, don’t talk of such a thing on such a beautiful day,” Angela objected.

“They heard another of them last night,” Peter Brady commented. “They’ve been hearing this one, off and on, for a week now, and haven’t caught him yet.”

“I always wish they wouldn’t kill them when they catch them,” Angela bemoaned. “It doesn’t seem quite right to kill them.”

A goose-girl was herding her white honking charges as they gobbled weeds out of fields of morning onions. Flowering kale was shining green-purple, and okra plants were standing. Jersey cows grazed along the roadway, and the patterned plastic (almost as patterned as the grasses) filled the roadway itself.

There were clouds like yellow dust in the air. Bees! Stingless bees they were. But dust itself was not. That there never be dust again!

“They will have to find out and kill the sly klunker makers,” said old man Charles Archer. “Stop the poison at its source.”

“There’s too many of them, and too much money in it,” said Peter Brady. “Yes, we kill them. One of them was found and killed Thursday, and three nearly finished klunkers were destroyed. But we can’t kill them all. They seem to come out of the ground like snakes.”

“I wish we didn’t have to kill them,” Angela said.

There were brightly colored firkins of milk standing on loading stoas, for this was a milk shed. There were chickens squawking in nine-story-high coops as they waited the pickups, but they never had to wait long. Here were a thousand dozen eggs on a refrigeration porch; there a clutch of piglings, or of red steers.

Tomato plants were staked two meters high. Sweetcorn stood, not yet come to tassel. They passed cucumber vines and cantaloupe vines, and the potato hills rising up blue-green. Ah, there were grapevines in their tight acres, deep alfalfa meadows, living fences of Osage orange and white-thorn. Carrot tops zephyred like green lace. Cattle were grazing fields of red clover and of peanuts—that most magic of all clovers. Men mowed hay.

“I hear him now!” Peter Brady said suddenly.

“You couldn’t. Not in the daytime. Don’t even think of such a thing,” Angela protested.

Farm ducks were grazing with their heads under water in the roadway ponds and farm ponds. Bower oaks grew high in the roadway parks. Sheep fed in hay grazer that was higher than their heads; they were small white islands in it. There was local wine and choc beer and cider for sale at small booths, along with limestone sculpture and painted fruitwood carvings. Kids danced on loading stoas to little post-mounted music canisters, and goats licked slate outcroppings in search of some new mineral.

The Saturday riders passed a roadway restaurant with its tables out under the leaves and under a little rock overhang. A one-meter-high waterfall gushed through the middle of the establishment, and a two-meter-long bridge of set shale stone led to the kitchen. Then they broke onto view after never-tiring view of the rich and varied quasiurbia. The roadway farms, the fringe farms, the berry patches! In their seasons: Juneberries, huckleberries, blueberries, dewberries, elderberries, highbush cranberries, red raspberries, boysenberries, loganberries, nine kinds of blackberries, strawberries, greenberries.

Orchards! Can there ever be enough orchards? Plum, peach, sand plum and chokecherry, black cherry, apple and crab apple, pear, blue-fruited pawpaw, persimmon, crooked quince. Melon patches, congregations of beehives, pickle patches, cheese farms, flax farms, close clustered towns (twenty houses in each, twenty persons in a house, twenty of the little settlements along every mile of roadway), country honky-tonks, as well as high-dog clubs already open and hopping with action in the early morning; roadway chapels with local statuary and with their rich-box-poor-boxes (one dropped money in the top if one had it and the spirit to give it, one tripped it out the bottom if one needed it), and the little refrigeration niches with bread, cheese, beef rolls, and always the broached cask of country wine: that there be no more hunger on the roadways forever!

“I hear it too!” old Charles Archer cried out suddenly. “High-pitched and off to the left. And there’s the smell of monoxide and—gah—rubber. Conductor, conductor!”

The conductor heard it, as did others in the car. The conductor stopped the cars to listen. Then he phoned the report and gave the location as well as he might, consulting with the passengers. There was rough country over to the left, rocks and hills, and someone was driving there in broad daylight.

The conductor broke out rifles from the locker, passing them out to Peter Brady and two other young men in the car, and to three men in each of the other two cars. A competent-seeming man took over the communication, talking to men on a line further to the left, beyond the mad driver, and they had him boxed into a box no more than half a mile square.

“You stay, Angela, and you stay, Grandfather Archer,” Peter Brady said. “Here is a little thirty carbine. Use it if he comes in range at all. We hunt him down now.” Then Peter Brady followed the conductor and the rifle-bearing men, ten men on a death hunt. And there were now four other groups out on the hunt, converging on their whining, coughing target.

“Why do they have to kill them, Great-grandfather? Why not turn them over to the courts?”

“The courts are too lenient. All they give them is life in prison.”

“But surely that should be enough. It will keep them from driving the things, and some of the unfortunate men might even be rehabilitated.”

“Angela, they are the greatest prison breakers ever. Only ten days ago, Mad Man Gudge killed three guards, went over the wall at State Prison, evaded all pursuit, robbed the cheesemakers’ cooperative of fifteen thousand dollars, got to a sly klunker maker, and was driving one of the things in a wild area within thirty hours of his breakout. It was four days before they found him and killed him. They are insane, Angela, and the mental hospitals are already full of them. Not one of them has ever been rehabilitated.”

“Why is it so bad that they should drive? They usually drive only in the very wild places, and for a few hours in the middle of the night.”

“Their madness is infectious, Angela. Their arrogance would leave no room for anything else in the world. Our country is now in balance, our communication and travel is minute and near perfect, thanks to the wonderful trolleys and the people of the trolleys. We are all one neighborhood, we are all one family! We live in love and compassion, with few rich and few poor, and arrogance and hatred have all gone out from us. We are the people with roots, and with trolleys. We are one with our earth.”

“Would it hurt that the drivers should have their own limited place to do what they wanted, if they did not bother sane people?”

“Would it hurt if disease and madness and evil were given their own limited place? But they will not stay in their place, Angela. There is the diabolical arrogance in them, the rampant individualism, the hatred of order. There can be nothing more dangerous to society than the man in the automobile. Were they allowed to thrive, there would be poverty and want again, Angela, and wealth and accumulation. And cities.”

Читать дальше

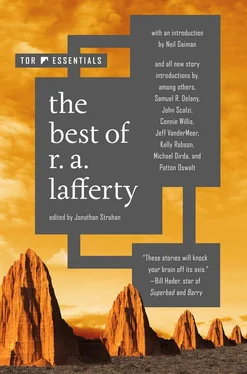

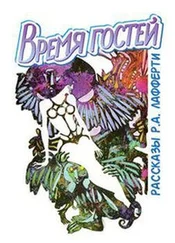

![Рафаэль Лафферти - Дни, полные любви и смерти. Лучшее [сборник litres]](/books/385123/rafael-lafferti-dni-polnye-lyubvi-i-smerti-luchshe-thumb.webp)

![Рафаэль Лафферти - Лучшее [Сборник фантастических рассказов]](/books/401500/rafael-lafferti-luchshee-sbornik-fantasticheskih-ra-thumb.webp)