Enjoy the peep show.

Thus We Frustrate Charlemagne

“We’ve been on some tall ones,” said Gregory Smirnov of the Institute, “but we’ve never stood on the edge of a bigger one than this, nor viewed one with shakier expectations. Still, if the calculations of Epiktistes are correct, this will work.”

“People, it will work,” Epikt said.

This was Epiktistes the Ktistec machine? Who’d have believed it? The main bulk of Epikt was five floors below them, but he had run an extension of himself up to this little penthouse lounge. All it took was a cable, no more than a yard in diameter, and a functional head set on the end of it.

And what a head he chose! It was a sea-serpent head, a dragon head, five feet long and copied from an old carnival float. Epikt had also given himself human speech of a sort, a blend of Irish and Jewish and Dutch comedian patter from ancient vaudeville. Epikt was a comic to his last para-DNA relay when he rested his huge, boggle-eyed, crested head on the table there and smoked the biggest stogies ever born.

But he was serious about this project.

“We have perfect test conditions,” the machine Epikt said as though calling them to order. “We set out basic texts, and we take careful note of the world as it is. If the world changes, then the texts should change here before our eyes. For our test pilot, we have taken that portion of our own middle-sized city that can be viewed from this fine vantage point. If the world in its past-present continuity is changed by our meddling, then the face of our city will also change instantly as we watch it.

“We have assembled here the finest minds and judgments in the world: eight humans and one Ktistec machine, myself. Remember that there are nine of us. It might be important.”

The nine finest minds were: Epiktistes, the transcendent machine who put the “K” in Ktistec; Gregory Smirnov, the large-souled director of the Institute; Valery Mok, an incandescent lady scientist; her over-shadowed and over-intelligent husband, Charles Cogsworth; the humorless and inerrant Glasser; Aloysius Shiplap, the seminal genius; Willy McGilly, a man of unusual parts (the seeing third finger on his left hand he had picked up on one of the planets of Kapteyn’s Star) and no false modesty; Audifax O’Hanlon; and Diogenes Pontifex. The latter two men were not members of the Institute (on account of the Minimal Decency Rule), but when the finest minds in the world are assembled, these two cannot very well be left out.

“We are going to tamper with one small detail in past history and note its effect,” Gregory said. “This has never been done before openly. We go back to an era that has been called ‘A patch of light in the vast gloom,’ the time of Charlemagne. We consider why that light went out and did not kindle others. The world lost four hundred years by that flame expiring when the tinder was apparently ready for it. We go back to that false dawn of Europe and consider where it failed. The year was 778, and the region was Spain. Charlemagne had entered alliance with Marsilies, the Arab king of Saragossa, against the Caliph Abd ar-Rahmen of Córdova. Charlemagne took such towns as Pamplona, Huesca, and Gerona and cleared the way to Marsilies in Saragossa. The Caliph accepted the situation. Saragossa should be independent, a city open to both Moslems and Christians. The northern marches to the border of France should be permitted their Christianity, and there would be peace for everybody.

“This Marsilies had long treated Christians as equals in Saragossa, and now there would be an open road from Islam into the Frankish Empire. Marsilies gave Charlemagne thirty-three scholars (Moslem, Jewish, and Christian) and some Spanish mules to seal the bargain. And there could have been a cross-fertilization of cultures.

“But the road was closed at Roncesvalles where the rearguard of Charlemagne was ambushed and destroyed on its way back to France. The ambushers were more Basque than Moslems, but Charlemagne locked the door at the Pyrenees and swore that he would not let even a bird fly over that border thereafter. He kept the road closed, as did his son and his grandsons. But when he sealed off the Moslem world, he also sealed off his own culture.

“In his latter years he tried a revival of civilization with a ragtag of Irish half-scholars, Greek vagabonds, and Roman copyists who almost remembered an older Rome. These weren’t enough to revive civilization, and yet Charlemagne came close with them. Had the Islam door remained open, a real revival of learning might have taken place then rather than four hundred years later. We are going to arrange that the ambush at Roncesvalles did not happen and that the door between the two civilizations was not closed. Then we will see what happens to us.”

“‘Intrusion like a burglar bent,’” said Epikt.

“Who’s a burglar?” Glasser demanded.

“I am,” Epikt said. “We all are. It’s from an old verse. I forget the author; I have it filed in my main mind downstairs if you’re interested.”

“We set out a basic text of Hilarius,” Gregory continued. “We note it carefully, and we must remember it the way it is. Very soon, that may be the way it was. I believe that the words will change on the very page of this book as we watch them. Just as soon as we have done what we intend to do.”

The basic text marked in the open book read:

The traitor Gano, playing a multiplex game, with money from the Córdova Caliph hired Basque Christians (dressed as Saragossan Mozarabs) to ambush the rear-guard of the Frankish force. To do this it was necessary that Gano keep in contact with the Basques and at the same time delay the rearguard of the Franks. Gano, however, served both as guide and scout for the Franks. The ambush was effected. Charlemagne lost his Spanish mules. And he locked the door against the Moslem world.

That was the text by Hilarius.

“When we, as it were, push the button (give the nod to Epiktistes), this will be changed,” Gregory said. “Epikt, by a complex of devices which he has assembled, will send an Avatar (partly of mechanical and partly of ghostly construction), and something will have happened to the traitor Gano along about sundown one night on the road to Roncesvalles.”

“I hope the Avatar isn’t expensive,” Willy McGilly said. “When I was a boy we got by with a dart whittled out of slippery elm wood.”

“This is no place for humor,” Glasser protested. “Who did you, as a boy, ever kill in time, Willy?”

“Lots of them. King Wu of the Manchu, Pope Adrian VII, President Hardy of our own country, King Marcel of Auvergne, the philosopher Gabriel Toeplitz. It’s a good thing we got them. They were a bad lot.”

“But I never heard of any of them, Willy,” Glasser insisted.

“Of course not. We killed them when they were kids.”

“Enough of your fooling, Willy,” Gregory cut it off.

“Willy’s not fooling,” the machine Epikt said. “Where do you think I got the idea?”

“Regard the world,” Aloysius said softly. “We see our own middle-sized town with half a dozen towers of pastel-colored brick. We will watch it as it grows or shrinks. It will change if the world changes.”

“There’s two shows in town I haven’t seen,” Valery said. “Don’t let them take them away! After all, there are only three shows in town.”

“We regard the Beautiful Arts as set out in the reviews here which we have also taken as basic texts,” Audifax O’Hanlon said. “You can say what you want to, but the arts have never been in meaner shape. Painting is of three schools only, all of them bad. Sculpture is the heaps-of-rusted-metal school and the obscene tinker-toy effects. The only popular art, graffiti on mingitorio walls, has become unimaginative, stylized, and ugly.

Читать дальше

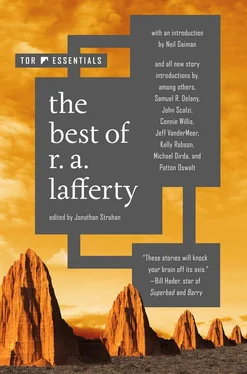

![Рафаэль Лафферти - Дни, полные любви и смерти. Лучшее [сборник litres]](/books/385123/rafael-lafferti-dni-polnye-lyubvi-i-smerti-luchshe-thumb.webp)

![Рафаэль Лафферти - Лучшее [Сборник фантастических рассказов]](/books/401500/rafael-lafferti-luchshee-sbornik-fantasticheskih-ra-thumb.webp)