“But cities are the most wonderful things of all! I love to go to them.”

“I do not mean the wonderful Excursion Cities, Angela. There would be cities of another and blacker sort. They were almost upon us once when a limitation was set on them. Uniqueness is lost in them; there would be mere accumulation of rootless people, of arrogant people, of duplicated people, of people who have lost their humanity. Let them never rob us of our involuted countryside, or our quasiurbia. We are not perfect; but what we have, we will not give away for the sake of wild men.”

“The smell! I cannot stand it!”

“Monoxide. How would you like to be born in the smell of it, to live every moment of your life in the smell of it, to die in the smell of it?”

“No, no, not that.”

The rifleshots were scattered but serious. The howling and coughing of the illicit klunker automobile were nearer. Then it was in sight, bouncing and bounding weirdly out of the rough rock area and into the tomato patches straight toward the trolley interurban.

The klunker automobile was on fire, giving off the ghastly stench of burning leather and rubber and noxious monoxide and seared human flesh. The man, standing up at the broken wheel, was a madman, howling, out of his head. He was a young man, but sunken-eyed and unshaven, bloodied on the left side of his head and the left side of his breast, foaming with hatred and arrogance.

“Kill me! Kill me!” he croaked like clattering broken thunder. “There will be others! We will not leave off driving so long as there is one desolate place left, so long as there is one sly klunker maker left!”

He went rigid. He quivered. He was shot again. But he would die howling.

“Damn you all to trolley haven! A man in an automobile is worth a thousand men on foot! He is worth a million men in a trolley car! You never felt your black heart rise up in you when you took control of one of the monsters! You never felt the lively hate choke you off in rapture as you sneered down the whole world from your bouncing center of the universe! Damn all decent folks! I’d rather go to hell in an automobile than to heaven in a trolley car!”

A spoked wheel broke, sounding like one of the muted volleys of rifle fire coming from behind him. The klunker automobile pitched onto its nose, upended, turned over, and exploded in blasting flames. And still in the middle of the fire could be seen the two hypnotic eyes with their darker flame, could be heard the demented voice:

“The crankshaft will still be good, the differential will still be good, a sly klunker maker can use part of it, part of it will drive again— ahhhiiii. ”

Some of them sang as they rode away from the site in the trolley cars, and some of them were silent and thoughtful. It had been an unnerving thing.

“It curdles me to remember that I once put my entire fortune into that future,” Great-grandfather Charles Archer moaned. “Well, that is better than to have lived in such a future.”

A young couple had happily loaded all their belongings onto a baggage trolley and were moving from one of the Excursion Cities to live with kindred in quasiurbia. The population of that Excursion City (with its wonderful theaters and music halls and distinguished restaurants and literary coffeehouses and alcoholic oases and amusement centers) had now reached seven thousand persons, the legal limit for any city: oh, there were a thousand Excursion Cities and all of them delightful! But a limit must be kept on size. A limit must be kept on everything.

It was a wonderful Saturday afternoon. Fowlers caught birds with collapsible kite-cornered nets. Kids rode free out to the diamonds to play Trolley League ball. Old gaffers rode out with pigeons in pigeon boxes, to turn them loose and watch them race home. Shore netters took shrimp from the semi-saline Little Shrimp Lake. Banjo players serenaded their girls in grassy lanes.

The world was one single bronze gong song with the melodious clang of trolley cars threading the country on their green-iron rails, with the sparky fire following them overhead and their copper gleaming in the sun. By law there must be a trolley line every mile, but they were oftener. By law no one trolley line might run for more than twenty-five miles. This was to give a sense of locality. But transfers between the lines were worked out perfectly. If one wished to cross the nation, one rode on some one hundred and twenty different lines. There were no more long-distance railroads. They also had had their arrogance, and they also had had to go.

Carp in the ponds, pigs in the clover, a unique barn factory in every hamlet and every hamlet unique, bees in the air, pepper plants in the lanes, and the whole land as sparky as trolley fire and right as rails.

THUS WE FRUSTRATE CHARLEMAGNE

Introduction by Jack Dann

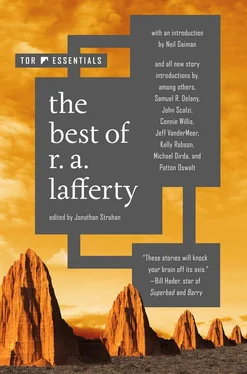

Rump of Skunk and Madness, or How to Read R. A. Lafferty

Yes, it looks perfectly simple on the surface … Lafferty’s prose is short on adjectives and long on what would seem to be the voice of the American tall tale. His characters are ciphers, seemingly one-dimensional caricatures; and the tall voice is innocently jocular as it seems to invent its own convoluted syntax, explains historical incidents at length, punctuates events with impossibly over-the-top details, and tramples through philosophical swamplands like Paul Bunyan in a hurry to get to the end of the story.

We can’t help but notice that there is more going on than we can see; and although there are bits and pieces we don’t understand—words we don’t know, incidents and outré theories that may or may not be historically correct, ostensibly irrelevant sidebars—we can’t get off the runaway train until it … stops. As is widely acknowledged, Lafferty is a one-off. He can’t be imitated. He’s been compared to Gene Wolfe because of the influence and presence of Christianity in his work; and he’s been compared to Mark Twain, probably for the yarnish nature of his prose. But comparisons don’t really work with Lafferty. After all the comparisons are made, we are still left wondering what the hell just happened after we read a Lafferty story. And why do these stories stick in our minds like childhood memory, like fairy tales that scared the bejesus out of us…?

Perhaps it’s because they are just that: philosophical fairy tales for adults.

And so to “Thus We Frustrate Charlemagne,” which for my money is one of his best short stories; it is quintessential Lafferty, and it works on all the levels, sure to leave you scratching your head as the parable(?) inserts itself firmly into your memory. The story is classic counterfactual fiction: it is an illustration of what happens when you change history to create alternate history; and it comes into being through the writer’s choice of a divergence point, which creates a new branch that confounds history as we (think we) know it. Lafferty will leave you to tangle with the possible consequences of the battle of Roncesvalles and William of Occam’s concept of terminalism. And if you’re as obsessive as I am, you’ll probably find yourself looking up some terms.

All that aside, consider as you read whether this is a science fiction story at all … or whether it might just be an anti–science fiction story.1 The author playfully uses the tropes of science fiction, of alternate history; but the science is pretty much just another version of magic, a trope in itself. And the history … we believe it because Lafferty sprinkles in such learned esoterica that it somehow feels right. And some of it is!

Suffice it to say the story you’re about to read is simple and confusing and makes absolute sense! Welcome to the antinomical Lafferty. Welcome to his happily constructed dystopia. As the critic and scholar Don Webb said, “Lafferty’s fiction creates the Unknown rather than the Known.”

Читать дальше

![Рафаэль Лафферти - Дни, полные любви и смерти. Лучшее [сборник litres]](/books/385123/rafael-lafferti-dni-polnye-lyubvi-i-smerti-luchshe-thumb.webp)

![Рафаэль Лафферти - Лучшее [Сборник фантастических рассказов]](/books/401500/rafael-lafferti-luchshee-sbornik-fantasticheskih-ra-thumb.webp)