“Due to the high average elevation of Stutzamutza (there will be some boggled eyes when I reveal just what I do mean by the average elevation of this place), the people are all wonderfully deep-chested or deep-breasted. They are like something out of fable. The few visitors who come here from lower, from more mundane elevations, are uniform in their disbelief. ‘Oh, oh,’ they will say. ‘There can’t be girls like that.’ There are, however (see plate VIII). ‘How long has this been going on?’ these occasional visitors ask. It has been going on for the nine thousand years of recorded Stutzamutza history; and, beyond that, it has been going on as long as the world has been going on.

“Perhaps due to their deep-breastedness the Stutzamutza people are superb in their singing. They are lusty, they are loud, they are beautiful and enchanting in this. Their instruments, besides the conventional flutes and bagpipes (with their great lung-power, these people do wonderful things with the bagpipes) and lyric harps and tabors, are the thunder-drum (plate IX) and the thirteen-foot-long trumpets (plates X and XI). It is doubted whether any other people anywhere would be able to blow these roaring trumpets.

“Perhaps it is due also to their deep-breastedness that the Stutzamutza people are all so lustily affectionate. There is something both breath-taking and breath-giving in their Olympian carnality. They have a robustness and glory in their man and woman interfluents that leave this underdeveloped little girl more than amazed (plates X to XIX). Moreover, these people are witty and wise, and always pleasant.

“It is said that originally there was not any soil at all on Stutzamutza. The people would trade finest quality limestone, marble, and dolomite for equal amounts of soil, be it the poorest clay or sand. They filled certain crevices with this soil and got vegetation to begin. And, in a few thousand years, they built countless verdant terraces, knolls, and valleys. Grapes, olives, and clover are now grown in profusion. Wine and oil and honey gladden the deep hearts of the people. The wonderful blue-green clover (see plate XX) is grazed by the bees and the goats. There are two separate species of goat: the meadow and pasture goat kept for its milk and cheese and mohair, and the larger and wilder mountain goat hunted on the white crags and eaten for its flavorsome, randy meat. Woven mohair and dressed buckskin are used for the Stutzamutza clothing. The people are not voluminously clothed, in spite of the fact that it becomes quite chilly on the days when the elevation suddenly increases.

“There is very little grain grown on Stutzamutza. Mostly, quarried stones are bartered for grain. Quarrying stone is the main industry, it is really the only one on Stutzamutza. The great quarries in their cutaways sometimes reveal amazing fossil deposits. There is a complete fossilized body of a whale (it is an extinct Zeuglodon or Eocene Whale) (see plate XXI).

‘If this is whale indeed, then this all must have been under ocean once,’ I said to one of my deep-chested friends. ‘Oh certainly,’ he said, ‘nowhere else is limestone formed than in ocean.’ ‘Then how has it risen so far above it?’ I asked. ‘That is something for the Geologists and the Hyphologists to figure out,’ my friend said.

“The fascinating aspect of the water on Stutzamutza is its changeableness. A lake is sometimes formed in a single day, and it may be emptied out in one day again by mere tipping. The rain is prodigious sometimes, when it is decided to come into that aspect. To shoot the rapids on the sudden swollen rivers is a delight. Sometimes ice will form all over Stutzamutza in a very few minutes. The people delight in this sudden ice, all except the little under-equipped guest. The beauty of it is stupendous; so is its cold. They shear the ice off in great sheets and masses and blocks, and let it fall for fun.

“But all lesser views are forgotten when one sees the waterfalls tumbling in the sunlight. And the most wonderful of all of them is Final Falls. Oh to watch it fall clear off Stutzamutza (see plate XXII), to see it fall into practically endless space, thirty thousand feet, sixty thousand feet, turning into mist, into sleet or snow or rain or hail depending on the sort of day it is, to see the miles-long rainbow of it extending to the vanishing point so far below your feet!

“There is a particularly striking pink marble cliff toward the north end of the land (the temporary north end of the land). ‘You like it? You can have it,’ my friends say. That is what I had been fishing for them to say.”

Yes, Miss Phosphor McCabe did the really stunning photographic article for Heritage Geographical Magazine . Heritage Geographical did not accept it, however. Miss Phosphor McCabe had arrived at some unacceptable conclusions, the editor said.

“What really happened is that I arrived at an unacceptable place,” Miss Phosphor said. “I remained there for six days. I photographed it and I narrated it.”

“Ah, we’d never get by with that,” the editor said. Part of the trouble was Miss Phosphor McCabe’s explanations of just what she did mean by the average elevation of Stutzamutza (it was quite high), and by “days of increasing elevation.”

Now here is another stone of silly shape. At first glimpse, it will not seem possible to fit it into the intended gap. But the eye is deceived: this shape will fit into the gap nicely. It is a recollection in age of a thing observed during a long lifetime by a fine weather eye.

Already as a small boy I was interested in clouds. I believed that certain clouds preserve their identities and appear again and again; and that some clouds are more solid than others.

Later, when I took meteorology and weather courses at the university, I had a classmate who held a series of seemingly insane beliefs. At the heart of these was the theory that certain apparent clouds are not vapor masses at all but are floating stone islands in the sky. He believed that there were some thirty of these islands, most of them composed of limestone, but some of them of basalt or sandstone, even of shale. He said that one, at least, of them was composed of pot-stone or soap-stone.

This classmate said that these floating islands were sometimes large, one of them being at least five miles long: that they were intelligently navigated to follow the best camouflage, the limestone islands usually traveling with masses of white fleecy clouds, the basalt islands traveling with dark thunder-heads, and so on. He believed that these islands sometimes came to rest on earth, that each of them had its own several nests in unfrequented regions. And he believed that the floating islands were peopled.

We had considerable fun with Mad Anthony Tummley, our eccentric classmate. His ideas, we told each other, were quite insane. And, indeed, Anthony himself was finally institutionalized. It was a sad case, but one that could hardly be discussed without laughter.

But later, after more than fifty years in the weather profession, I have come to the conclusion that Anthony Tummley was right in every respect. Several of us veteran weathermen share this knowledge now, but we have developed a sort of code for the thing, not daring to admit it openly, even to ourselves. “Whales in the Sky” is the code-name for this study, and we pretend to keep it on a humorous basis.

Some thirty of these floating stone islands are continuously over our own country (there may be more than a hundred of them in the world). They are tracked on radar; they are sighted again and again in their slightly changed forms (some of them, now and then, seem to slough off small masses of stone and deposit it somehow on earth); they are known, they are named.

They are even visited by some persons of odd character: always a peculiar combination of simplicity, acceptance, intelligence, and strange rapport. There are persons and families in rural situations who employ these peopled islands to carry messages and goods for them. In rural and swampland Louisiana, there was once some wonder that the people did not more avail themselves of the Intercoastal Canal barges to carry their supplies, and their products to market. “How are the barges better than the stone islands that we have always used?” these people ask. “They aren’t on a much more regular schedule, they aren’t much faster, and they won’t give you anything like the same amount of service in exchange for a hundredweight of rice. Besides that, the stone-island people are our friends, and some of them have intermarried with us Cajuns.” There are other regions where the same easy cooperation obtains.

Читать дальше

![Рафаэль Лафферти - Дни, полные любви и смерти. Лучшее [сборник litres]](/books/385123/rafael-lafferti-dni-polnye-lyubvi-i-smerti-luchshe-thumb.webp)

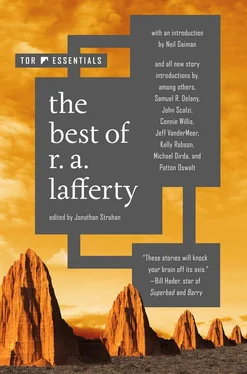

![Рафаэль Лафферти - Лучшее [Сборник фантастических рассказов]](/books/401500/rafael-lafferti-luchshee-sbornik-fantasticheskih-ra-thumb.webp)