Listen to this:

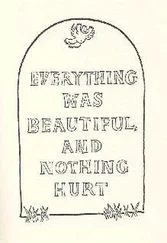

"I wish to tell you," he said, "that I am an innocent man. I never committed any crime, but sometimes some sin. I am innocent of all crime — not only this one, but all crime. I am an innocent man." He had been a fish peddler at the time of his arrest.

"I wish to forgive some people for what they are now doing to me," he said. The lights of the prison dimmed three times.

The story yet again:

Sacco and Vanzetti never killed anybody. They arrived in America from Italy, not knowing each other, in Nineteen-hundred and Eight. It was the same year in which my parents arrived.

Father was nineteen. Mother was twenty-one.

Sacco was seventeen. Vanzetti was twenty. American employers at that time wanted the country to be flooded with labor that was cheap and easily cowed, so that they could keep wages down.

Vanzetti would say later, "In the immigration station, I had my first surprise. I saw the steerage passengers handled by the officials like so many animals. Not a word of kindness, of encouragement, to lighten the burden of tears that rest heavily upon the newly arrived on American shores."

Father and Mother used to tell me much the same thing. They, too, were made to feel like fools who had somehow gone to great pains to deliver themselves to a slaughterhouse.

My parents were recruited at once by an agent of the Cuyahoga Bridge and Iron Company in Cleveland. He was instructed to hire only blond Slavs, Mr. McCone once told me, on his father's theory that blonds would have the mechanical ingenuity and robustness of Germans, but tempered with the passivity of Slavs. The agent was to pick up factory workers, and a few presentable domestic servants for the various

McCone households, as well. Thus did my parents enter the servant class.

Sacco and Vanzetti were not so lucky. There was no broker in human machinery who had a requisition for shapes like theirs. "Where was I to go? What was I to do?" wrote Vanzetti. "Here was the promised land. The elevated rattled by and did not answer. The automobiles and the trolleys sped by heedless of me." So he and Sacco, still separately and in order not to starve to death, had to begin at once to beg in broken English for any sort of work at any wage — going from door to door.

Time passed.

Sacco, who had been a shoemaker in Italy, found himself welcome in a shoe factory in Milford, Massachusetts, a town where, as chance would have it, Mary Kathleen O'Looney's mother was born. Sacco got himself a wife and a house with a garden. They had a son named Dante and a daughter named Inez. Sacco worked six days a week, ten hours each day. He also found time to speak out and give money and take part in demonstrations for workers on strike for better wages and more humane treatment at work and so on. He was arrested for such activities in Nineteen-hundred and Sixteen.

Vanzetti had no trade and so went from job to job — in restaurants, in a quarry, in a steel mill, in a rope factory. He was an ardent reader. He studied Marx and Darwin and Hugo and Gorki and Tolstoi and Zola and Dante. That much he had in common with Harvard men. In Nineteen-hundred and Sixteen he led a strike against the rope factory, which was The Plymouth Cordage Company in Plymouth, Massachusetts, now a subsidiary of RAMJAC. Hs was blacklisted by places of work far and wide after that, and became a self-employed peddler of fish to survive.

And it was in Nineteen-hundred and Sixteen that Sacco and Vanzetti came to know each other well. It became evident to both of them, thinking independently, but thinking always of the brutality of business practices, that the battlefields of World War One were simply additional places of hideously dangerous work, where a few men could supervise the wasting of millions of lives in the hopes of making money. It was clear to them, too, that America would soon become involved. They did not wish to be compelled to work in such factories in Europe, so they both joined the same small group of Italian-American anarchists that went to Mexico until the war was over.

Anarchists are persons who believe with all their hearts that governments are enemies of their own people.

I find myself thinking even now that the story of Sacco and Vanzetti may yet enter the bones of future generations. Perhaps it needs to be told only a few more times. If so, then the flight into Mexico will be seen by one and all as yet another expression of a very holy sort of common sense.

Be that as it may: Sacco and Vanzetti returned to Massachusetts after the war, fast friends. Their sort of common sense, holy or not, and based on books Harvard men read routinely and without ill effects, had always seemed contemptible to most of their neighbors. Those same neighbors, and those who liked to guide their destinies without much opposition, now decided to be terrified by that common sense, especially when it was possessed by the foreign-born.

The Department of Justice drew up secret lists of foreigners who made no secret whatsoever about how unjust and self-deceiving and ignorant and greedy they thought so many of the leaders were in the so-called "Promised Land." Sacco and Vanzetti were on the list. They were shadowed by government spies.

A printer named Andrea Salsedo, who was a friend of Vanzetti's, was also on the list. He was arrested in New York City by federal agents on unspecified charges, and held incommunicado for eight weeks. On May third of Nineteen-hundred and Twenty, Salsedo fell or jumped or was pushed out of the fourteenth-story window of an office maintained by the Department of Justice.

Sacco and Vanzetti organized a meeting that was to demand an investigation of the arrest and death of Salsedo. It was scheduled for May ninth in Brockton, Massachusetts, Mary Kathleen O'Looney's home town. Mary Kathleen was then six years old. I was seven.

Sacco and Vanzetti were arrested for dangerous radical activities before the meeting could take place. Their crime was the possession of leaflets calling for the meeting. The penalties could be stiff fines and up to a year in jail.

But then they were suddenly charged with two unsolved murders, too. Two payroll guards had been shot dead during a robbery in South Braintree, Massachusetts, about a month before.

The penalties for that, of course, would be somewhat stiffer, would be two painless deaths in the same electric chair.

Vanzetti, for good measure, was also charged with an attempted payroll robbery in Bridgewater, Massachusetts. He was tried and convicted. Thus was he transmogrified from a fish peddler into a known criminal before he and Sacco were tried for murder.

Was Vanzetti guilty of this lesser crime? Possibly so, but it did not matter much. Who said it did not matter much? The judge who tried the case said it did not matter much. He was Webster Thayer, a graduate of Dartmouth College and a descendent of many fine New England families. He told the jury, "This man, although he may not have actually committed the crime attributed to him, is nevertheless morally culpable, because he is the enemy of our existing institutions."

Word of honor: This was said by a judge in an American court of law. I take the quotation from a book at hand: Labor's Untold Story, by Richard O. Boyer and Herbert M. Morais. (United Front: San Francisco, 1955.)

And then this same Judge Thayer got to try Sacco and the known criminal Vanzetti for murder. They were found guilty about one year after their arrest — in July of Nineteen-hundred and Twenty-one, when I was eight years old.

They were finally electrocuted when I was fifteen. If I heard anybody in Cleveland say anything about it, I have forgotten now.

I talked to a messenger boy in an elevator in the RAMJAC Building the other morning. He was about my age. I asked him if he remembered anything about the execution when he was a boy. He said that, yes, he had heard his father say he was sick and tired of people talking about Sacco and Vanzetti all the time, and that he was glad it was finally over with.

Читать дальше