"I've had the same dream of myself," I said. "Many's the time, Mary Kathleen, that I've wished it were true."

"No! No! No!" she protested. "Thank God you're still alive! Thank God there's somebody still alive who cares what happens to this country. I thought maybe I was the last one. I've wandered this city for years now, Walter, saying to myself, They've all died off, the ones who cared.' And then there you were."

"Mary Kathleen," I said, "you should know that I just got out of prison."

"Of course you did!" she said. "All the good people go to prison all the time. Oh, thank God you're still alive! We will remake this country and then the world. I couldn't do it by myself, Walter."

"No — I wouldn't think so," I said.

"I've just been hanging on for dear life," she said. "I haven't been able to do anything but survive. That's how alone I've been. I don't need much help, but I do need some."

"I know the problem," I said.

"I can still see enough to write, if I write big," she said, "but I can't read the stories in newspapers anymore. My eyes — " She said she sneaked into bars and department stores and motel lobbies to listen to the news on television, but that the sets were almost never tuned to the news. Sometimes she would hear a snatch of news on somebody's portable radio, but the person owning it usually switched to music as soon as the news began.

Remembering the news I had heard that morning, about the police dog that ate a baby, I told her that she wasn't really missing much.

"How can I make sensible plans," she said, "if I don't know what's going on?"

"You can't," I said.

"How can you base a revolution on Lawrence Welk and Sesame Street and All in the Family! " she said. All these shows were sponsored by RAMJAC.

"You can't," I said. j

"I need solid information," she; said.

"Of course you do," I said. "We all do."

"It's all such crap," she said. "I find this magazine called People in garbage cans," she said, "but it isn't about people. It's about crap."

This all seemed so pathetic to me: that a shopping-bag lady hoped to plan her scuttlings about the city and her snoozes among ash cans on the basis of what publications and radio and television could tell her about what was really going on.

It seemed pathetic to her, too. "Jackie Onassis and Frank Sinatra and the Cookie Monster and Archie Bunker make their moves," she said, "and then I study what they have done, and then I decide what Mary Kathleen O'Looney had better do.

"But now I have you," she said. "You can be my eyes — and my brains!"

"Your eyes, maybe," I said. "I haven't distinguished myself in the brains department recently."

"Oh — if only Kenneth Whistler were alive, too," she said.

She might as well have said, "If only Donald Duck were alive, too." Kenneth Whistler was a labor organizer who had been my idol in the old days — but I felt nothing about him now, had not thought about him for years.

"What a trio we would make," she went on. "You and me and Kenneth Whistler!"

Whistler would have been a bum, too, by now, I supposed — if he hadn't died in a Kentucky mine disaster in Nineteen-hundred and Forty-one. He had insisted on being a worker as well as a labor organizer, and would have found modern union officials with their soft, pink palms intolerable. I had shaken hands with him. His palm had felt like the back of a crocodile. The lines in his face had had so much coal dust worked into them that they looked like black tattoos. Strangely enough, this was a Harvard man — the class of Nineteen-hundred and Twenty-one.

"Well," said Mary Kathleen, "at least there's still us — and now we can start to make our move."

"I'm always open to suggestions," I said.

"Or maybe it isn't worth it," she said.

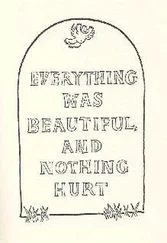

She was talking about rescuing the people of the United States from their economy, but I thought she was talking about life in general. So I said of life in general that it probably was worth it, but that it did seem to go on a little too long. My life would have been a masterpiece, for example, if I had died on a beach with a fascist bullet between my eyes.

"Maybe people are just no good anymore," she said. "They all look so mean to me. They aren't like they were during the Depression. I don't see anybody being kind to anybody anymore. Nobody will even speak to me."

She asked me if I had seen any acts of kindness anywhere.

I reflected on this and I realized that I had encountered almost nothing but kindness since leaving prison. I told her so.

"Then it's the way I look," she said. This was surely so. There was a limit to how much reproachful ugliness most people could bear to look at, and Mary Kathleen, and all her shopping-bag sisters had exceeded that limit.

She was eager to know about individual acts of kindness toward me, to have it confirmed that Americans could still be good-hearted. So I was glad to tell her about my first twenty-four hours as a free man, starting with the kindnesses shown to me by Clyde Carter, the guard, and then by Dr. Robert Fender, the supply clerk and science-fiction writer. After that, of course, I was given a ride in a limousine by Cleveland Lawes.

Mary Kathleen exclaimed over these people, repeated their names to make sure she had them right. "They're saints!" she said. "So there are still saints around!"

Thus encouraged, I embroidered on the hospitality offered to me by Dr. Israel Edel, the night clerk at the Arapahoe, and then by the employees at the Coffee Shop of the Hotel Royal-ton on the following morning. I was not able to give her the name of the owner of the shop, but only the physical detail that set him apart from the populace. "He had a French-fried hand," I said.

"The saint with the French-fried hand," she said wonderingly.

"Yes," I said, "and you yourself saw a man I thought was the worst enemy I had in the world. He was the tall, blue-eyed man with the sample case. You heard him say that he forgave me for everything I had done, and that I should have supper with him soon."

"Tell me his name again," she said.

"Leland Clewes," I said.

"Saint Leland Clewes," she said reverently. "See how much you've helped me already? I never could have found out about all these good people for myself." Then she performed a minor mnemonic miracle, repeating all the names in chronological order. "Clyde Carter, Dr. Robert Fender, Cleveland Lawes, Israel Edel, the man with the French-fried hand, and Leland Clewes."

Mary Kathleen took off one of her basketball shoes. It wasn't the one containing the inkpad and her pens and paper and her will and all that. The shoe she took off was crammed with memorabilia. There were hypocritical love letters from me, as I've said. But she was particularly eager for me to see a snapshot of what she called " . . . my two favorite men."

It was a picture of my one-time idol, Kenneth Whistler, the Harvard-educated labor organizer, shaking hands with a small and goofy-looking college boy. The boy was myself. I had ears like a loving cup.

That was when the police finally came clumping in to get me.

"I'll rescue you, Walter," said Mary Kathleen. "Then we'll rescue the world together."

I was relieved to be getting away from her, frankly. I tried to seem regretful about our parting. "Take care of yourself, Mary Kathleen," I said. "It looks like this is good-bye."

I hung that snapshot of Kenneth Whistler and myself, taken in the autumn of Nineteen-hundred and Thirty-five, dead center in the Great Depression, on my office wall at RAMJAC — next to the circular about stolen clarinet parts. It was taken by Mary Kathleen, with my bellows camera, on the morning after we first heard Whistler speak. He had come all the way to Cambridge from Harlan County, Kentucky, where he was a miner and a union organizer, to address a rally whose purpose was to raise money and sympathy for the local chapter of the International Brotherhood of Abrasives and Adhesives Workers.

Читать дальше