We both stood by his shoulder, and watched as he connected first one wire then another! Soon only one remained bare.

“Now!”

Mr Wells touched the last wires together, and in that instant the whole apparatus—wheel, crystals and wires—vanished from our sight.

“It works!” I cried in delight, and Mr Wells beamed up at me.

“That is how we enter the attenuated dimension,” he said. “As you know, as soon as the crystals are connected, the entire piece becomes attenuated. By connecting the device that way, I tapped the power that resides in the dimension, and my little experiment is now lost to us forever.”

“Where is it, though?” I said.

“I cannot say for certain, as it was a test-piece only. It is certainly moving in Space, at a very slow speed, and will continue to do so for ever. It is of no importance to us, for the secret of travel through the attenuated dimension is how we may control it. That is my next task.”

“Then how long will it be before we can build a new Machine?” I said.

“It will be several days more, I think.”

“We must be quick,” I said. “With every day that passes the monsters tighten their hold on our world.”

“I am working as fast as I am able,” Mr Wells said without rancour, and then I noticed how his eyes showed dark circles around them. He had often been working in the laboratory long after Amelia and I had taken to our beds. “We shall need a frame in which the mechanism can be carried, and one large enough to carry passengers. I believe Miss Fitzgibbon has already had an idea about this, and if you and she were to concentrate on this now, our work will end soon enough.”

“But a new Machine will be possible?” I said.

“I see no reason why it should not,” said Mr Wells. “Now we have no desire to travel to futurity, our Machine need not be nearly so complicated as Sir William’s”

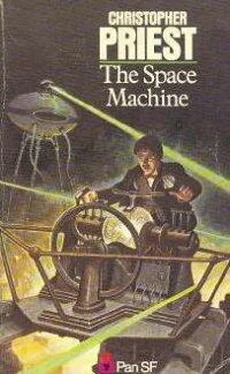

Eight more days passed with agonizing slowness, but at last we saw the Space Machine taking shape.

Amelia’s plan had been to use the frame of a bed as a base for the Machine, as this would provide the necessary sturdiness and space for the passengers. Accordingly, we searched the damaged servants’ wing, and found an iron bedstead some five feet wide. Although it was coated with grime after the fire, it took less than an hour to clean it up. We carried it to the laboratory, and under Mr Wells’s guidance began to connect to it the various pieces he produced. Much of this comprised the crystalline substance, in such quantities that it was soon clear that we would need every piece we could lay our hands on. When Mr Wells saw how quickly our reserves of the mysterious substance were being used up he expressed his doubts, but we pressed on nonetheless.

Knowing that we intended to travel in this Machine our selves, we left enough room for somewhere to sit, and with this in mind I fitted out one end of the bedstead with cushions.

While our secret work continued in the laboratory, the Martians themselves were not idle.

Our hopes that military reinforcements would be able to deal with the incursion had been without foundation, for whenever we saw one of the battle-machines or legged vehicles in the valley below, it strode unchallenged and arrogant. The Martians were apparently consolidating their gains, for we saw much equipment being transferred from the various landing-pits in Surrey to London, and on many occasions we saw groups of captive people either being herded by or driven in one of the legged ground vehicles. The slavery had begun, and all that we had ever feared for Earth was coming to pass.

Meanwhile, the scarlet weed continued to flourish: the Thames Valley was an expanse of garish red, and scarcely a tree was left alive on the side of Richmond Hill. Already, shoots of the weeds were starting to encroach on the lawn of the house, and I made it my daily duty to cut it back. Where the lawn met the weeds was a muddy and slippery morass.

“I have done all I can,” said Mr Wells, as we stood before the outlandish contraption that once had been a bed. “We need many more crystals, but I have used all we could find.”

Nowhere in any of Sir William’s drawings had there been so much as a single clue as to the constituency of the crystals. Therefore, unable to manufacture any more, Mr Wells had had to use those that Sir William had left behind. We had emptied the laboratory, and dismantled the four adapted bicycles which still stood in the outhouse, but even so Mr Wells declared that we needed at least twice as much crystalline substance as we had. He explained that the velocity of the Machine depended on the power the crystals produced.

“We have reached the most critical moment,” Mr Wells went on. “The Machine, as it stands, is simply a collection of circuitry and metal. As you know, once it is activated it must stay permanently attenuated, and so I have had to incorporate an equivalent of Sir William’s temporal fly-wheel. Once the Machine is in operation, that wheel must always turn so that it is not lost to us.”

He was indicating our makeshift installation, which was the wheel of the artillery piece blown off in the explosion. We had mounted this transversely on the front of the bedstead.

Mr Wells took a small, leather-bound notebook from his breast pocket, and glanced at a list of handwritten instructions he had compiled himself. He passed this to Amelia, and as she called them out one by one, he inspected various critical parts of the Space Machine’s engine. At last he declared himself satisfied.

“We must now trust to our work,” he said softly, returning the notebook to his pocket. Without ceremony he placed one stout piece of wire against the iron frame of the bedstead, and turned a screw to hold it in place. Even before he had finished, Amelia and I noticed that the artillery wheel was turning slowly.

We stood back, hardly daring to hope that our work had been successful.

“Turnbull, kindly place your hand against the frame.”

“Will I receive an electrical shock?” I said, wondering why he did not do this himself.

“I should not think so. There is nothing to be afraid of.”

I extended my hand cautiously, then, catching Amelia’s eye and seeing that she was smiling a little, I reached out resolutely and grasped the metal frame. As my fingers made contact the entire contraption shuddered visibly and audibly, just as had Sir William’s Time Machine; the solid iron bedstead became as lissom as a young tree.

Amelia stretched out her hand, and then so did Mr Wells. We laughed aloud.

“You’ve done it, Mr Wells!” I said. “We have built a Space Machine!”

“Yes, but we have not tested it yet. We must see if it can be safely driven.”

“Then let us do it at once!”

Mr Wells mounted the Space Machine, and, sitting comfortably on the cushions, braced himself against the controls. By working a combination of levers he managed to shift the Machine first forwards and backwards, then to each side. Finally, he took the unwieldy Machine and drove it all around the laboratory.

None of this was seen by Amelia and myself. We have only Mr Wells’s word that he tested the Machine this way… for as soon as he touched the levers he and the Machine instantly became invisible, reappearing only when the Machine was turned off.

“You cannot hear me when I speak to you?” he said, after his tour of the laboratory.

“We can neither hear nor see you,” said Amelia. “Did you call to us?”

“Once or twice,” Mr Wells said, smiling. “Turnbull, how does your foot feel?”

“My foot, sir?”

“I regret I inadvertently passed through it on my journey. You would not pull it out of the way when I called to you.”

Читать дальше