Fred Hoyle - The Black Cloud

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Fred Hoyle - The Black Cloud» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Фантастика и фэнтези, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Black Cloud

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Black Cloud: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Black Cloud»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Black Cloud — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Black Cloud», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

The gradual elucidation of the true nature of the black cloud also gives fascinating insights into the way scientists think and argue among themselves. The hero, the Cambridge theoretical astronomer Christopher Kingsley, whom it is hard not to identify with Hoyle himself, and the Russian astronomer Alexandrov, who is the book’s comic relief character, independently tumble to the startling truth — so startling that other characters stubbornly refuse to accept it. Kingsley and Alexandrov relentlessly insist that theories should be tested by prediction , and they gradually win over the sceptics. Once again, there is absorbing drama in the unfolding dialogue between cooperating and dissenting scientists.

Once the strange nature of the cloud is established, things move rapidly. In this part of the story one of the scientific lessons we learn is about information theory. Information is a commodity, readily interchangeable from one medium to another. Beethoven moves us via our ears, but in principle there is no reason why an alien being — or an advanced computer, say, with no sense of hearing at all — shouldn’t enjoy the music if supplied with the same temporal patternings (which might be hugely speeded up or slowed down), and the same mathematical relationships between frequencies — the ones that we interpret as melody and harmony. In information theory, the medium of transmission is arbitrary. This idea has been very influential on me in my scientific career, and I acknowledge that I first came to appreciate it through reading The Black Cloud as a young man.

A related point, of deep scientific and philosophical significance, is that the subjective individuality that each of us feels inside our skull depends upon the slowness and other imperfections of the channels of communication between us, for example language. If we could share our thoughts instantly by telepathy, fully and at the same rate as we can think them, we would cease to be separate individuals. Or, to put it another way, the very idea of separate individuality would lose its meaning. This, indeed, is arguably what did happen in the evolution of the nervous system. It is a thought that has intrigued me for much of my career as a biologist, and I was again led to it by reading The Black Cloud.

Arthur C. Clarke, a more consistent writer of good science fiction than Hoyle, although he only equalled Hoyle at his best, stated as his ‘Third Law’ that ‘any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic.” The Black Cloud reinforces the message in spades. Pizarro fired his cannon, and was taken for a god by the Incas. Imagine if he had arrived in a helicopter gunship instead of on a horse. Imagine the response of a medieval peasant, or even aristocrat, to a telephone, a television, a laptop computer, a jumbo jet. The Black Cloud vividly conveys to us what it would be like to be visited by an extraterrestrial being whose intelligence would seem god-like from our lowly point of view. Indeed, Hoyle’s imagination far outperforms all religions known to me. Would such a super-intelligence then actually be a god?

An interesting question, perhaps the founding question of a new discipline of ‘Scientific Theology’. The answer, it seems to me, turns not on what the super-intelligence is capable of doing, but on its provenance. Alien beings, no matter how advanced their intelligence and accomplishments, would presumably have evolved by something like the same gradual evolutionary process as gave rise to our kind of life. And this is where Hoyle makes this book’s only scientific blunder, in my opinion. The eponymous super-intelligence of The Black Cloud is asked about the origin of the first member of its species, and it replies, “I would not agree that there ever was a “first” member.” The response of the astronomers in the story is an in-joke by Hoyle: ‘Kingsley and Marlowe exchanged a glance as if to say: “Oh-ho, there we go. That’s one in the eye for the exploding-universe boys”.” Never mind the astronomers, I must protest as a biologist. Even if Hoyle and his colleagues had been right that the universe has been in a steady state forever, the same could not sensibly be claimed for the organized and apparently purposeful complexity that life epitomizes. Galaxies may spring spontaneously into existence, but complex life cannot. That is pretty much what complexity means !

There are other flaws in the novel. Despite the wonderfully true-to-life picture it paints of how scientists think, the dialogue occasionally becomes a little clunky, the jokes a little heavy. The character of the hero, Christopher Kingsley, always on the abrasive side, rises to heights — or descends to depths — of inhumane fanaticism in a horrifying scene near the end of the book, which one reviewer described as ‘a fascinating glimpse into the scientific power dream’ but which struck me as way over the top.

Ever since I first read this book, a phrase from it has haunted me: ‘the Deep Problems’. These are the problems in science that we do not understand, perhaps can never understand, either because of the limitations of our evolved minds or because they are in principle insoluble. How did the universe begin, and how will it end? Can something come from nothing? Whence the laws of physics? Why do the fundamental constants have the particular values that they do? What about other questions that are so far beyond us that we cannot even ask , let alone answer them? The idea of the Deep Problems, and the possibility that they might be understood by a superior intelligence but not by us, is humbling, but humbling in a way that is at the same time uplifting. It is also challenging.

The tragic ending of the novel is moving and deeply thought-provoking at the same time. It is followed by a gentle epilogue — again the contemplation by the log fire — which pulls the threads together and leaves us on a high. The last words leave us exhilarated, even stunned, as we look back on this astonishing novel: ‘Do we want to remain big people in a tiny world or to become a little people in a vaster world? This is the ultimate climax towards which I have directed my narrative.”

1

The details of Weichart’s remarks and work while at the blackboard were as follows: Write α for the present angular diameter of the cloud, measured in radians,

d for the linear diameter of the cloud,

D for its distance away from us,

V for its velocity of approach,

T for the time required for it to reach the solar system.

To make a start, evidently we have α = d/D

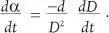

Differentiate this equation with respect to time t and we get

But  so that we can write

so that we can write

Also we have  Hence we can get rid of V , arriving at

Hence we can get rid of V , arriving at

This is turning out easier than I thought. Here’s the answer already

The last step is to approximate  by finite intervals,

by finite intervals,  , where Δ t = 1 month corresponding to the time difference between Dr Jensen’s two plates; and from what Dr Marlowe has estimated Δα is about 5 per cent of α, i.e Therefore T = 20Δ t = 20 months.

, where Δ t = 1 month corresponding to the time difference between Dr Jensen’s two plates; and from what Dr Marlowe has estimated Δα is about 5 per cent of α, i.e Therefore T = 20Δ t = 20 months.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Black Cloud»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Black Cloud» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Black Cloud» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.