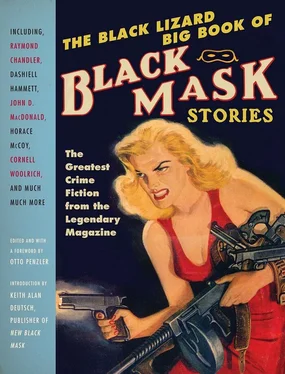

The Black Lizard Big Book of Black Mask Stories

For Michael Connelly

Whose generous friendship

can never be repaid

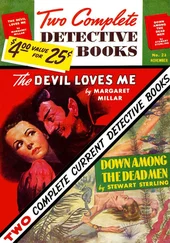

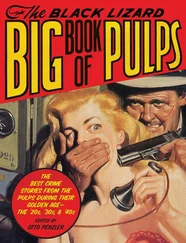

This is not the first anthology to be devoted entirely to the mystery fiction contained in the pages of Black Mask magazine, but I am confident that I will be accused of neither hyperbole nor immodesty when I state unequivocally that it is the biggest and most comprehensive. Indeed, apart from The Black Lizard Big Book of Pulps, published by Vintage in 2007 and to which this volume is a sequel of sorts, The Black Lizard Big Book of Black Mask Stories is the biggest and most comprehensive collection of pulp crime fiction ever published.

The first anthology of Black Mask stories, The Hard-Boiled Omnibus (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1946), was compiled and edited by the legendary editor Joseph T. Shaw, who was more responsible than anyone else for the elevation of the magazine to the stature it achieved during his tenure and which it still enjoys today, all these years after it ceased publication. Had he done nothing more than write to Dashiell Hammett to encourage him to produce a detective story for the magazine, Shaw would still have gone down in the history of the American mystery story as one of its handful of most significant and influential figures. This groundbreaking book was subtitled “Early Stories from Black Mask ” and contained fifteen stories by many of the stalwarts who regularly contributed to the magazine, eleven of whom are also in these pages, though not with the same stories. While the remaining four authors had some historical interest, the fact that they have gone on to be largely forgotten today is not pure happenstance. Few readers of this current volume will lament the absence of J. J. des Ormeaux, Reuben Jennings Shay, and Ed Lybeck; the fourth, the excellent Roger Torrey, failed to be included only because I reluctantly had to accept the fact that even the thickest book in the store has a finite number of pages. Perhaps it is a greater surprise to note the absence in Shaw’s compilation of some of Black Mask ’s most beloved authors, including Erle Stanley Gardner, Carroll John Daly, Frederick Nebel, and Cornell Woolrich.

A quarter of a century after the magazine went out of business, Herbert Ruhm edited a paperback original, The Hard-Boiled Detective (New York: Vintage, 1977), that contained fourteen stories. Again, most of those authors are represented on the pages of this book, with only three failing to make the cut: William Brandon, Paul W. Fairman, and Curt Hamlin. Strangely, the greatest of all suspense writers, Cornell Woolrich, was also omitted from this otherwise exemplary anthology, as were Horace McCoy (absent from Shaw as well) and Raoul Whitfield (represented twice in Shaw’s book, the only author so honored, both under his own name and as Ramon Decolta).

Seven years later, William F. Nolan, a pulp fiction expert and a talented writer of stories and novels in his own right, compiled The Black Mask Boys (New York: William Morrow, 1984). Subtitled Masters in the Hard-Boiled School of Detective Fiction, this handsome volume contained a mere eight stories but managed to nail most of the big names (Chandler, Daly, Gardner, Hammett, McCoy, Nebel, Whitfield), all of whom are included in the present volume. As is Woolrich, who once again was omitted from the otherwise stellar lineup.

The biggest names in the crime fiction pulp world were all published by Black Mask, and it should be noted that they didn’t become names because of expensive advertising campaigns or because of the excesses of their private lives. They achieved it the old-fashioned way — by putting to work the genius with which they were blessed, producing much of the greatest hard-boiled fiction ever written.

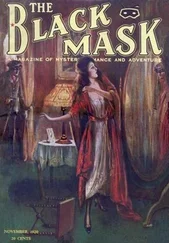

If you are an aficionado of this type of literature, as most serious readers of fiction are, you will have noticed that so many stories, even by the best pulp writers, are virtually impossible to find. Copies of the original Black Mask magazines turn up in used bookstores and on eBay from time to time, with the early issues commanding prices in the hundreds of dollars. They are so rare that only two (and a rumored third) complete collections of Black Mask exist; one is at the Library of Congress and the other is in the hands of a private collector. The Special Collections department of UCLA has a superb collection and the good people who are involved in its day-to-day activities, notably Octavio Olvera, have been enormously helpful and generous in making these elusive stories available, and my sincere thanks go out to them. Likewise, Clark W. Evans and Margaret Kieckhefer at the Library of Congress have disproved the notion that all government agencies are inefficient and unfriendly. Thanks to them for filling gaps with copies of some of the most impossibly rare issues.

Finally, a note of appreciation to Keith Alan Deutsch, who wrote the introduction to this monumental collection and who owns the Black Mask magazine name and a huge percentage of the material that appeared in it. It should be self-evident that this collection would have been impossible without his encouragement and cooperation, but, beyond the obvious, he has been unfailingly honorable and courteous in all the dealings I’ve had with him, making the compilation of this wonderful addition to the literature of vintage crime fiction a delightful experience, rather than an onerous chore.

— OTTO PENZLER

This panoramic collection of stories and novels from Black Mask magazine (1920 to 1951) is the most comprehensive presentation of the hard-boiled tradition of writing ever published from this great magazine. I believe this is a significant publishing event because Black Mask introduced the hard-boiled detective, and a new style of narration, to American literature.

In many ways, Black Mask took the nineteenth-century American Western tale of outlaws and vigilante justice from its home on the range in dime novels, and transplanted that mythic tale to the crooked streets of America’s emerging twentieth-century cities. It introduced a new landscape for both American adventures of justice and also a new kind of narration told with the vernacular language of the streets, and featuring new urban villains, and urban (if not always urbane) heroes for the mystery story.

The first hard-boiled detectives were men of the city, all: Carroll John Daly’s Three Gun Terry and Race Williams appeared primarily on the wild streets of New York, talking wise and walking that eternal tough-guy-detective line between the law and the outlaw. The first great detective narrator of the new hard-boiled fiction, Dashiell Hammett’s professional lawman, the Continental Op (the first Op tale is included in this collection), operated famously in San Francisco, as did Hammett’s iconic detective, Sam Spade.

Surprisingly, soon after the publication of The Maltese Falcon, Gertrude Stein declared Hammett, not Hemingway, the originator of the modern American, declarative, narrative sentence.

Arguably the greatest stylist of the hard-boiled genre, Raymond Chandler, observed such a fully realized and corrupting Los Angeles landscape in his poetic vision of the Black Mask detective tale that his writing has become the literary standard for all twentieth-century narratives of that city, or of any other American city.

All of this said, I do not mean to imply that the hard-boiled Black Mask detective always operated in a big city.

Race Williams’s first appearance in the magazine in 1923, “Knights of the Open Palm,” took place in a Southern, rural setting, and featured the KKK for Black Mask ’s all-KKK issue (!). In 1925, Hammett’s San Francisco Op headed out to Arizona for what was billed by Black Mask editors as “a Western detective novelette” in the story “Corkscrew.” This tale, by the way, might be considered a warm-up for what I consider to be the Op’s finest novel, Red Harvest, a kind of Western-town gang showdown that inspired Akira Kurosawa’s film Yojimbo and the Sergio Leone Man with No Name series of Western films.

Читать дальше