“Know?”

“Well, it’s pretty obvious. One of the layers of the plateau, just below the foot of the cliff, has to be ammonia. That’s mineral there. A lot of it was melted by the falling rock, and the Mesklinites smelled it—”

“Smelled something like it.”

“What else could that be?”

“How do I know? I’m not a Mesklinite.” A third voice cut in. “The two of you are just gabbling. We haven’t seen a layer that looked like ammonia — it’d be white, like ice.”

“It would be ice.”

“All right, but we haven’t seen any.”

“It’s underground at river level.”

“But how could—?”

“That’s what I’m saying! We’ve got to check — I mean, Barlennan’s people have to check—”

“How? They don’t have drills, or shovels, or picks, and you can’t expect a Mesklinite to go tunneling, do you?” The captain had never heard this verb, but context suggested its meaning, rather too clearly. “Why not? Barlennan’s had lots of time underground now, and he’s still all right.”

“How do you know he is?” The captain started to tune out, as usual. Just another of the theory-based wrangles among Flyers, which of course might lead to something later. Then he saw what the something probably would be. The Flyers were very persuasive beings— Any being with muscles and a nervous system complex enough to consider alternatives consciously can shudder. Dondragmer was obviously listening, too.

INTRODUCTION TO “LECTURE DEMONSTRATION”

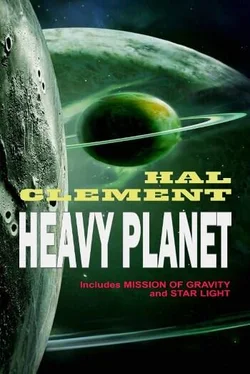

From Astounding: John W. Campbell Memorial Anthology, edited by Harry Harrison, Random House, 1973

I have been a high-school teacher for a quarter of a century, a student for nearly twice as long. “Lecture Demonstration” may show me as the former to people who did not know John Campbell, but not to those who did. He bought my first story over thirty years ago when I was a college sophomore. Since then we have exchanged thousands of words of correspondence and spent many, many hours in conversation. We sometimes agreed, sometimes did not. I was trained in theory — astronomy and chemistry — and still tend to center my extrapolation on one factor alone, like a politician. John’s education was in engineering, and he tended to remember better than I that all the rules are working at once: when he focused on one, it was to start an argument. We were alike in one way. The phrase “of course” set either of us going. It’s such fun to take apart a remark where those words appear! To show why, or how, or under what circumstances it isn’t true at all! That attitude was the seed of Mission of Gravity, the story on which I am content (so far) to let my reputation rest, and how much of that story was John is for future Ph. D. candidates to work out. He provided none of the specific scientific points, for once, but the general attitude underlying it was so obviously Campbellian that I have been flattered more than once to hear that “of course” Hal Clement was a Campbell pseudonym. He would certainly have had as much fun writing Mission of Gravity as I did. Low-gravity planets and high-gravity planets were old hat to science-fiction fans, but, of course, no one planet can vary greatly in its gravity. So, naturally, Mesklin was born, thousands of times the mass of Earth, but whirling so rapidly on its axis that its equatorial diameter is more than twice the polar value, less than eighteen minutes pass from noon to noon, and a man massing a hundred and eighty pounds weighs five hundred and forty at Mesklin’s equator and nearly sixty tons at its poles. Its people were fun to make up too. Little, many-legged types afraid of flying away with the wind at their low-gravity equator, about at the cultural level of Marco Polo — and one of them at least was a much sharper trader. He followed along very cooperatively when the strange beings from the sky hired him, until he had them where he wanted them. Then he held out — for scientific knowledge. Of Course one doesn’t interfere with the development of a primitive tribe by teaching it modern technology. “Lature Demonstration” takes place during the formative years of the College on Mesklin, when the teachers are still learning too, and Mesklinites are finding that human beings are quite human. Whatever that may mean.

The wind wasn’t really strong enough to blow him away, but Estnerdole felt uneasy on his feet just the same. The ground was nearly bare rock, a grayspeckled, wind-polished reddish mass which the voice from the tank had been calling a “sediment.” It was dotted every few yards with low, wide-spreading, rubbery bushes whose roots had somehow eaten their way into a surface which the students’ own claws could barely scratch. Of course the plants themselves could provide anchorage if necessary. The ex-sailor’s nippers were tensed, ready to seize any branch that might come in handy if he did slip. While the gusts of hydrogen sweeping up from the sea at his right wouldn’t have provided much thrust for a sail, the feeble gravity of Mesklin’s equator — less than two percent of what he was used to in the higher latitudes — made Estnerdole feel as though anything at all could send him flying. It took a long time, as he had been warned, to get used to conditions at the world’s Rim; even the bulky metal tank crawling beside him seemed somehow unsteady. He was beginning to wonder whether he had been right to sign on for the College — the weird establishment where beings from the sky taught things that only the most imaginative Mesklinites had ever dreamed of. It would be fine to be able to perform miracles, of course, but the preliminaries — or what the aliens insisted were necessary preliminaries — got very dreary at times. This walk out on the peninsula, for example. How could the aliens know what the rocks below the surface were like, or what kind would appear at the surface at a given place, and how they had been folded up to make this long arm of dry land? And, most of all, why was any of this worth knowing? True, he had seen some of the holes drilled near the school and had even examined the cylinders of stone extracted from them; but how could anyone feel even moderately sure that things were the same a few cables away? It seemed like expecting the wind to blow from the north on one hilltop merely because it was doing the same on the next one. Well, the alien teachers said that questions should be asked when things weren’t clear. Maybe one would help here — if only Destigmet wouldn’t cut in with his own version of the answer. That was the worst of asking questions. You couldn’t be sure that everyone else didn’t already know the correct answer … But Estnerdole had learned a way around that. “Des!” he called, loudly enough to be sure that the other students would also hear. “I’m still not straight on one thing. The human said that this exercise was to tell whether the peninsula is a cuesta or a hogback. I still don’t see the difference. It seems to me that they could be pretty much the same thing. How do you know that anything you call a cuesta isn’t a small part of a hogback, or wouldn’t be if you looked over enough ground?” Destigmet started to answer in a self-assured tone, “It’s simply a matter of curvature. A cuesta is a flat layer of rock which has a softer layer under it which has eroded away, while a hogback—” He paused, and Estnerdole’s self-esteem took an upward turn. Perhaps this know-it-all was going to run aground on the same problem. If Des just had to give up and ask the instructor, everything would be solved. If he didn’t, at least there would be the fun of hearing him struggle through the explanation; and if it didn’t come easily, there would be nothing embarrassing about checking with the tank driver. The voice which came suddenly from the vehicle was therefore an annoyance and a disappointment. Estnerdole did not blame a malicious power for interfering with his hopes, since Mesklinites have little tendency toward superstition in the mystical sense, but he was not pleased. “We will turn south now,” the alien voice said in perfectly comprehensible, though accented, Stennish. “I haven’t said much yet, because the ground we’ve been covering is similar to that near the College. I hope you have a clear idea of what lies underneath there. You remember that the cores show about twelve meters of quartz sandstone and then over twenty of water ice, followed by several more layers of other silicate sediments. It shouldn’t have changed much out here. However, you will recall that along the center of this peninsula the surface looks white from space — you have been shown pictures. I am guessing, therefore, that erosion has removed the sandstone and uncovered the ice at the top of a long fold. This is of course extrapolation, and is therefore a risky conclusion. If I’m right, you will get some idea of what can be inferred from local measurements, and if I am wrong we will spend as much time as we can to find out why. “It will take us only a few minutes to reach the edge of the white strip. Any of you who don’t mind the climb may ride on the tank. Now, I want each of you to think out in as much detail as your knowledge and imagination permit just what the contact area should be like — thickness of sandstone near it, smoothness of the two surfaces, straightness of the junction, anything else which occurs to you. I know you may feel some uncertainty about making predictions on strictly dry-land matters, but remember I?m taking an even worse chance. You?re sailors, but at least you?re Mesklinites. I?m from a completely different world. There, I?m stopping; any of you who wish, climb on. Then we?ll head south.? Estnerdole decided to ride. The top of the tank was seven or eight body lengths above the ground and acrophobia is a normal, healthy state of mind for a Mesklinite; but College students were expected to practice overriding instinct with intelligence wherever possible. There would obviously be a better view of the landscape from the top of the vehicle. Estnerdole, Destigmet, and four of the remaining ten class members made their way up the sides of the machine by way of the ladderlike grips provided to suit their pincers. The other six elected to remain afoot. They took up positions beside and ahead of the tank as it resumed motion, the flickering legs which rimmed their fifteen-inch wormlike bodies barely visible to the giant alien inside as they kept pace with him. Visibility dropped as night fell, and for nearly nine minutes the tank’s floodlights guided the party. Then the sun reappeared on their left. By this time the edge of the dark rock they were traversing was visible from the tank roof, only a few hundred yards ahead. The teacher slowed, and as the ground party began to draw ahead, he called its members back. “Hold on. We’re almost close enough to check predictions, and I’d like to get a few of them on record first. Has anyone seen details yet which surprised him?” Estnerdole remained silent; he had made no predictions he would trust, and did not expect to be surprised by anything. Destigmet also said nothing, but his friend suspected that it was for a different reason. None of the others had anything to say either, and the teacher sighed inaudibly inside his machine. It was the same old story, and he knew better than to let the silence last too long. “There’s something I didn’t guess,” he finally said. “The edge of the dark rock isn’t as straight as I had expected — it looks almost wavy. Can anyone suggest why?” Destigmet spoke up after a brief pause. “How about the bushes? I see them growing along the edge. Could they have interfered with the erosion?”

Читать дальше