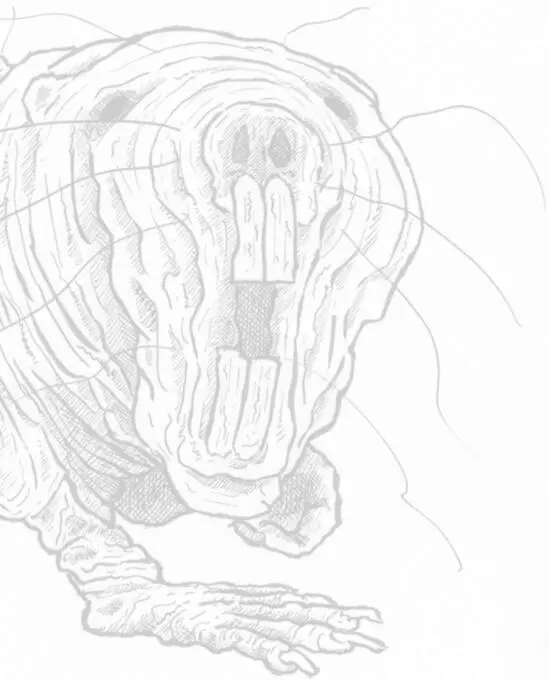

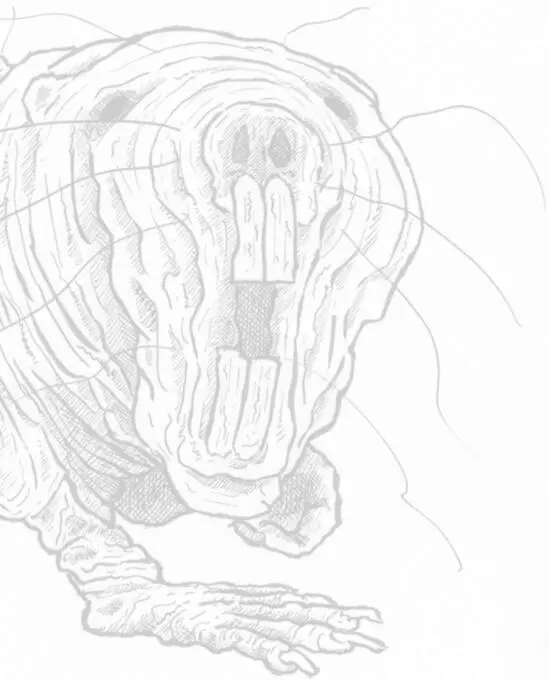

NAKED MOLE RAT

(Heterocephalus smilodon glaber)

Reproduced with permission from the archives of the Streggeye Molers’ Benevolent Society .

Credit: China Miéville (illustration credit 2.1)

A MOLETRAIN ON THE HUNT BEATS OUT ONE KIND OF rhythm. It is insistent, not too fast, stop-starting as it backs & forwards onto sidings, changes lines, trailing its prey, crews alert for give-away earthmounds.

One kind of rhythm: not one rhythm. The wheelbreath of hunts takes many shapes, but all instil in a moler a certainty, a calm energy, a controlled rush. They are all the default blood-quickening beats of the predator train. When old hunters hang up their trainboard gear, retire to a cottage on a crag to get up with the sun, it is one of those hunting rhythms to which their feet, unbidden & unnoticed, will move. Even in their coffins, some say, those are what the heels of a dead captain drum.

Very different is a train moving under emergency. Its rhythm is quite other. The Medes raced.

THE WHEELS SPOKE MOSTLY RADAGADAN , AT SPEED. One, two, three days after Unkus’s injury, the train ground north as fast as it safely could on such wild rails. Sham brought the sick man food. He held the bowls of hot water while the doctor changed the dressings. He could see the worsening state of the wounds, the creep of necrosis. Unkus’s legs suppurated.

These dusty barren stretches of plain-&-rails were near the edges of the world, & maps were contradictory. Captain Naphi & her officers annotated those they had. Kept the log up to date. The captain pored over her rumourbook. Sham would have loved a look at that.

The Medes headed north, but the eccentricities of rails & junctions took them briefly west, too. Enough that late one day, at the limits of vision, like a smoke wall at the horizon, loomed the slopes of Cambellia. A wild continent, a legend & a bad one, it rose from the railsea.

That would have been enough to get most of the crew out & staring at the horizon, but veering a little nearer it was clear that what might have been a line of bushes, some peculiarities of rock, was the fallen corpse of an upsky beast. Well that brought them all out. Muttering, pointing, taking flatographs.

It happened sometimes that those alien things fighting their obscure fights in the poisonous high air would kill each other, send each other’s strange carcases plummeting to the railsea. It wasn’t unprecedented for trains to have to grind slowly past or even through them, pushing impossible meat out of the way with their front-plows, their figureheads getting sticky with odd rot. “No flies on that, eh,” said Vurinam.

Upsky things tended to decay according to their own schedules & whatever grubs they carried in them. Most made earth maggots fastidious.

This, the first upsky corpse Sham had seen, was not very comprehensible. Long, stringy, knotted strands emerging out of ooze, bits of beak, bits of claw, splayed tendrils like ropes, if they weren’t bits of innard. No eyes he could see, but least two mouths, one like a leech’s, one like a buzz saw. Perhaps it was beautiful & delicate on the world on which its ancestors were born, where they had infested the ballast of some otherworldly vehicle during a brief stopoff, later to be sluiced off here on another, epochs ago.

Sham & Vurinam stood at the barrier of the forecastle, behind the howling engine. They looked away from the receding monster corpse to port at that miles-off country Cambellia. They glanced at each other. One at a time. Each only for a moment, when the other had looked away. The train’s figurehead, a traditional bespectacled man, jutted over the rails, staring woodenly away from their awkwardness.

They were not so far from Bollons. From whispers, the mutterings of the crew, Sham had ascertained that it was a soulless place, too close to poisonous upland, that in Bollons they would sell everything, including secrets & their mothers, without honour or hesitation.

Every railsea nation other than Streggeye, if it was discussed by many of the Streggeye-born trainsfolk, was, Sham noted, traduced. It was too big or small, too lax or strict, too mean, too gaudy, too plain, too foolishly munificent. Lands of all dimensions & governments met with disapproval. The scholarocracy of Rockvane was snootily intellectual. Cabigo, that quarrelsome federation of weak monarchies, was quarrelsomely monarchist. The warlords who ran Kammy Hammy were too brutish. Clarion was governed by priests whose piety was too much, while far-off Mornington needed a dose of religion. Manihiki, far the most powerful city-state in the railsea, brashly threw its weight around with wartrains, the grumbles went. & the democracy of which it crowed so loud was a sham, they added, in hoc to money.

& on & on. Similarity to its detractors’ home was no defence. Streggeye was one of several islands in the Salaygo Mess archipelago, in the railsea’s east, run by a council of elders & advised by eminent captains & philosophers, but it was, those xenophobes sniffed, the only one that didn’t do it wrong .

Sham nuzzled his recuperating daybat. It still not infrequently tried to bite him, but the force & frequency of the snaps was decreasing. Sometimes, like now, when he swaddled it, the animal buzzed with what Sham had learned was purring. Bat happiness.

“You ever been?” said Sham.

“Cambellia?” Vurinam pursed his lips. “Why would a person go there?”

“Exploring,” Sham said. He had no notion what governments there were on Cambellia to get things wrong & not be Streggeye. He stared towards it in fascination.

“When you’ve been trainsfolk as long as I have …” Vurinam began. Sham rolled his eyes. The trainswain was barely older than him. “I’m sure you must’ve heard stuff. Bad people, wild people,” Vurinam said. “Crazy things out there!”

“Sometimes,” Sham said, “it seems like every country in the railsea’s full of wild things & bad places & terrible animals. That’s all you ever hear.”

“Well,” Vurinam said. “What if they are? The thing is with a place like Cambellia, it’s the size of it. Miles & miles. Get me more than a day from the railsea lines, I get very twitchy. What I need to know’s that any moment, if things gets tricky, I can run to harbour, show my papers, get on a train, hightail away. A life on the open rails.” He breathed deep. Sham rolled his eyes again. “If you head northwest in Cambellia, you know where you get eventually?”

Remnants of geography lessons, remembered images from class ordinators, went through Sham’s head. “The Nuzland,” he said.

“The Nuzland.” Vurinam raised eyebrows. “Bloody hell, eh?”

The highest reaches of Cambellia climbed past where atmosphere shifted, up higher than where the carved gods, the Stonefaces, lived on Streggeye, into the upsky. The Nuzland wasn’t a pinnacle or a ridge. It was bigger by many times than Streggeye or Manihiki. Yes, Sham knew the stories, that somewhere there were whole bad plateau worlds in the upsky. Cities of the dead. Curdled high hells. Like the Nuzland, which was right over there. Sham could see its edge.

Vurinam muttered.

“What?” said Sham.

“Said sorry ,” Vurinam said. He was staring out to railsea. “Said I’m sorry for what I said to you. It weren’t your fault, what happened to Stone. Might as well say it was my fault for hitting him when I jumped in the cart.” The thought , Sham said to himself, had occurred . “Or Unkus’s fault for being in my way. Or for not holding on hard enough. Or that captain’s fault for wrecking the train leaving it for us to see. Whatever. I shouldn’t have shouted at you.”

Читать дальше